to do, you Tommy Yank?

A Touch of Nature

It was the 30th of May, and the sun was shining as it shines now. But the scene was far different. No one was dreaming then of Memorial day. We were merely doing the deeds that made this day possible.

The battle shifted to the the right and presently died to a mutter. I had been lying in a kind of stupor, but the sudden decrease in the the crash of the cannon and rifles—the change, I suppose it was—served me as a stimulant, and I revived. Although weak, I managed to shove the dead southerner off me with my shoulder and sit up. Then I undertook to raise my hand and pull my cap brim down over my eyes, as the sun was hot and pitiless. But the arm would not move, nor would the other when I tried it too. Now I remembered. The same bullet had broken both just as I was in the act of firing my own rifle. It was the shock that had thrown me into the daze or stupor from which I was just recovering. I sat quite still for a little while and felt my strength returning. And yet I looked at myself in a bewildered way. I was a strong man, but I was helpless. What can one do without arms, or what can he do even if he have arms and cannot use them?

As I meditated I looked again at the dead Confederate lying just as my feet, where I had pushed him when I rose. He had pitched through the smoke directly against me at the very moment the bullet had broken my arms, and we had fallen together. I gazed at him, having nothing else to do. He was young, as young as I, a handsome, fair faced fellow, with hair as yellow as straw.

“I dare say that this Johnny was quite a decent fellow in life,” I said to myself.

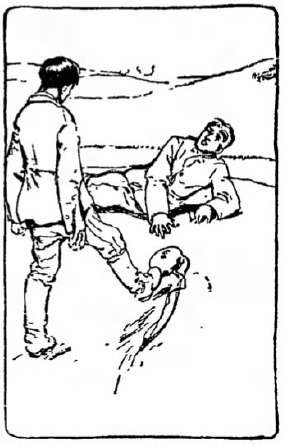

He was lying on his side, and I could see no wound on his face or on the upper part of his body. Perhaps he was shot on the other side of the head, I thought, and mechanically I undertook to turn him over and see. But the twinge in my arms warned me again that I could not raise them. Then I put my foot and gently pushed him until he lay upon his back. But, to my great surprise, he did not remain there. Instead he opened his eyes, rose to a sitting position and looked at me. Then I noticed how fine and frank his countenance was despite its pallor.

He seemed as much surprised as I.

“What were you trying to do, you Tommy Yank?” he said.

“I was merely seeking to find out where the bullet that killed you entered, you Johnny Reb,” I replied.

“I’m not dead,” he said, “but I thought sure you were, I saw you go down just before I fell.”

“It’s true I went down,” I replied loftily, “but I got up again. I’m not dead either.”

“No, you are not,” he replied thoughtfully. “and as we are both alive we are still at war, are we not?”

“Undoubtedly,” said I, with emphasis.

He mused a minute or two, and his face bore the appearance of great thought, but presently he brightened up.

“Then if we are still at war,” he said, “you are my prisoner.”

“Oh, no,” I replied; “you have made a mistake.”

“How so?”

“It is you who are my prisoner.”

He looked at me in surprose, but in a moment or two relapsed again into deep thought. Then he said:

“I do not see how you can take me a prisoner. I notice that you have been shot through both your arms and cannot move them.”

“That’s quite true,” I replied, “but I fail to see how you can get away from me. I observe that you have been shot in both legs and you cannot move them either.”

I told the exact truth. His would was through the legs. He had just discovered it himself and was making painful efforts to rise, but failed utterly. He muttered a groan of pain.

“Don’t try it again,” I said sympathetically. “You’ll only hurt yourself.”

“I shall not,” he replied. “But will you reach me my canteen over there?”

I thrust out my arm, and a pain shot through my shoulder and then through my body, thrilling every nerve. It was so sharp that I cried out.

“Forgive me, Yank,” said the Confederate. “I forgot that you couldn’t use your arms.”

“I forgot it, too,” I said ruefully.

Then we sat still and looked at each other sympathetically.

“Perhaps both of us will soon fall into the hands of somebody else,” he said presently.

“No,” I replied; “the battle has passed on and left us.”

It was true. We heard only the sound of a few distant shots like faint echoes. He said nothing, but looked at me in the manner of one both puzzled and troubled. Then I noticed again how young he was. I gnawed my mustache, which had begun to develop the year before.

“These wounds make one very thirsty,” he said a minute or two later, looking longingly at the canteen which lay in the sort grass, its polished tin sides shining in the sun like silver. I knew the truth of his words. My own throat was growing hot and dry. Then a happy thought occurred to me.

“If I can’t move my arms, I at least have legs to walk with and kick with,” I said.

I rose, walked over to the canteen, and, with three judicious kicks, drove it to the side of the Johnny.

“Good for you, Yank,” he said, his face lighting with anticipation. “You shall have half, and yours shall be the first to drink too. Kneel down here and I’ll raise it to your lips.”

“You go first,” I protested.

“Do as I tell you!” he said sternly.

I saw that he would take no nonsense, and so I obeyed. When I knelt down, he raised the canteen to my lips and turned it up. Then both of us uttered a cry of disgust. Not a drop came out. It was empty. He threw it as far as he could.

“If there’s anything I hate,” he said, “it’s an empty canteen on a hot day.”

We sat still again, looking at each other gloomingly for awhile. Our wounds had ceased to bleed, provident nature forming her own bandages of clotted blood. Our strength increased, and with it our thirst.

“There’s one thing sure, Yank,” said the Johnny, “we must have water.”

“I know it as well as you,” I replied, “but I don’t see how we are going to get it.”

He thought awhile and then pointed to a hillside about 30 yards away.

“Don’t you see some fallen soldiers lying over there?” he asked.

“Yes. There are at least five or six,” I replied.

“The chances are that half of them have canteens,” he said, “and there is another chance that of those canteens half have water in them.”

“Maybe I can bring one over here,” I said.

Rising, I walked to the hillside on which the falled soldiers lay, and there I found three canteens. I was sure by their weight against my feet that two of them contained water. One I could not detach from the man who had owned it, but the other I managed to push loose. Then I began to kick it toward the southerner. I carried it down the hillside all right, but it was necessary to cross the little ravine, and there that aggravating canteen lodged in a cranny that seem to have been made especially for it. I kicked again and again, but I could not budge it from the cranny. I only drove it deeper into the ground. I grew hot and angry, and I am afraid I swore. My wounds, too, began to pain me. The southerner was watching me, and presently he said:

“Give it up, Yank. You’ve done your best. Better sit down and rest, or you’ll work yourself into a fever.”

I saw that his advice was good, and, walking back, I sat down beside him. He uttered no reproach, but I saw his eyes wandering more that once to the canteen, which showed just the least bit through the grass, a patch of tin not larger than a silver quarter, shining directly into our eyes as if it would tantalize us. The day grew hotter. My thirst burned me, and my eyes, too, wandered to the canteen. At last they were held by it. They could not wander away. How I longed for the water! I had no doubt that the Confederate, too, was staring intently at that canteen. Then I had another of my happy thoughts.

“Reb,” I said, “do you think that you could climb upon my back?”

“I don’t know, Yank,” he replied, his face brightening wiht comprehension, but I can try.”

I knelt down in front of him and with my back turned to him. He was sitting on the edge of a shallow trench.

“Now clasp your arms tightly around my neck,” I said, “throw your weight forward and hold on with all your might when I get up.”

“All right,” he replied, “and be easy—because of my legs, you know.”

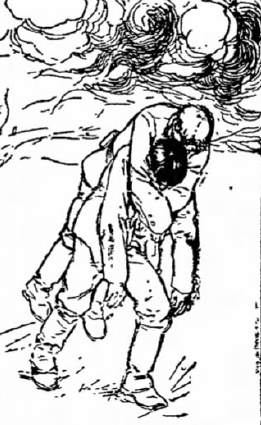

It was a great effort, as I had lost strength through my wound, but at last I managed to stagger to my feet, with the southerner on my back. Then he was able to steady my shoulders with his sound arms.

I walked slowly and painfully toward the ravine where the canteen lay, still shining in the most aggravating way. I thought once that I would drop with his weight, but I clinched my teeth and went on. I tried to avoid hurting his wounded legs, and he held on so carefully that he never sent a single twinge through my broken arms.

We reached the canteen, and I put him down with the greatest caution. Then both of us uttered a deep sigh of joy and exclaimed together, “At last!” We sat on either side of the canteen, and for a moment or two we gloated over it. He picked it up at length. “It’s full!” He exclaimed exultingly. It must be! It’s so heavy! Then he shook it. “Water, water!” he cried with increasing triumph. Don’t you hear it gurgle?”

I did hear it, and it was the most delicious sound I ever heard in my life.

He took out the stopper and bent his parched lips toward the canteen. I thought he was going to drink, but he raised his head again.

“Open your mouth,” he said sternly.

I obeyed and he poured the water between my lips and down my throat. I shall never find any greater delight in heaven. How delicious it was! How cool! He must have seen the pleaure in my eyes, because his own in sympathy reflected it. He took the canteen away at last. Then I shut my teeth firmly.

“I shall not drink another drop,” I said, “until you have swallowed as much as I have.”

He said nothing, but he drank deeply, heartily and drank with the most intense pleasure. Then I drank again, and, thus alternating, we divided the contents of the canteen. We lay back at last against the grass, and for the while were content.

“I feel like a new man,” he said.

“I know that I am one,” I replied.

As we lay there my eyes wandered again to the hillside where the fallen soldiers lay.

“Maybe there’s a knapsack with food in it on that hill,” I said.

“Maybe so,” he replied. “At any rate I’m getting hungry.”

“So am I,” I said. “Get upon my back again, Reb.”

He climbed up once more, and I carried him to the crest of the hill. There luck was again with us, and we found a knapsack with food in it. We ate it all and felt much stengthened.

“Now I think that I shall go to sleep,” said the southerner, stretching himself on his side. He had eatened and drunk heartily, and after a few minutes his eyes closed. I lingered longer, but after awhile I, too, went to sleep.

I was awakened by a roaring noise, and something hot struck me in the face. It was a cinder, and, opening my eyes, I saw a great sheet of flame. The dry woods, set on fire by the artillery and rifles, were blazing, and the flames, leaping and crackling, were rushing down upon us. The twigs snapped under the intense heat like a rifle fire, and the sparks in myriads floated off before the wind.

The southerner awoke, too, and sat up. His face was pale, but his voice was firm as he said:

“That fire will be on us in five minutes, Yank. If you go over the hill, you will strike a wide clearing, and beyond that the creek, which you can wade. On the other side you will be safe.”

I looked his steadily in the eye.

“We have eaten together,” I said, “and we have drunk together, and do you think that I am going to leave you? Get up on my back again or I swear I don’t move.”

I knelt down, and he climbed up. The hot breath of the fire was in our faces, but I felt strong now, and, while the flames roared behind us and the sparks flew over us, I walked with him on my back down the hill and through the clearing across the creek and into safety.