Black Feather’s Throw

They bound Hubbard to the tree with a single wrapping of the stout deer-hide thong, pressing his arms so tightly between his back and the bark that he could not move them. This was the position in which they liked to place a prisoner before they began such sport as they intended. He could move his head and shoulders with some freedom, but the thong held him fast to the tree, and prevented the use of his hands. He might twist and writhe and dodge, but he could not escape. Hubbard knew their plan well, and it did not seem to displease him. He made no resistance as they tied him to the tree, but he commented freely and offensively on the way in which they did it, speaking their language as fluently as they did themselves. He abused the warrior who knotted the thong for his lack of skill, and said if an eight-year-old boy of his proved himself so clumsy with his fingers he would give him many whippings. He told the warriors who put him in position that they were as awkward as an old buffalo with a broken leg, and only his consideration for their feelings kept him from pushing them over and running away. He lavished gibes and taunts upon those who stood by and looked on, telling them that they were lazy hounds, and in the white settlements such men as they were sent to the whipping-post.

All this talk was in accordance with the custom of the tribes, and the warriors rejoiced that their prisoner was proving himself a man of courage, for he promised good sport. Sometimes his taunts touched sore spots, but they made no visible sign. They went calmly on with their task, for such things must be done with gravity and precision, as they had been done from the beginning. The thong was knotted fast and the leading warrior stepped back to survey the work. Hubbard looked him squarely in the eye and abused the character of all his relatives, even to the farthest kin. He believed, moreover, that the chief was a squaw disguised as a warrior.

Hubbard did not take his eyes off the warriors. He did not wish, his sight to wander to the woods, which were his home and which he loved. He sought to check any rising regrets in these last moments. Then the chief stepped off the allotted space, spoke to the warriors, who ranged themselves, their guns laid aside, in a line facing the prisoner, and the sport began. But the same order and gravity that had marked the preparations were observed here. Each man took his turn, the youngest and least skilful first. The warrior who had shown impatience at Hubbard’s taunts raised his weapon. The chief bade him be careful, and the boy, with his reputation at stake, hurled the tomahawk. Hubbard watched him, and he saw that the wrist was steady. The weapon left the hand of the Indian, and, whirling over and over, sped toward him, a circle of glittering steel. Hubbard gazed upon it with unwinking eye, and there was a swish as the blade of the tomahawk buried itself in the tree just above his head. He did not move a muscle, but told the youth that a warrior who could not do better deserved a tomahawk in his own head.

The play of the tomahawks grew faster and the blades crept closer and closer to the body of the prisoner. Sometimes they made a ring of steel around his head and shoulders. Hubbard had never seen greater skill. He admitted it to himself, though he continued to taunt the warriors and call them squaws. As the blades cut into the tree he could feel the rush of air beside his face, and it required the greatest effort of his will to keep his nerves steady and make no motion, not even a quiver of the eyelid. The Indians, warming with the sport, began to talk to each other. They admired his courage and his control over his muscles and nerves, nor did they make any secret of their admiration. Why should they? They had not expected to find so stout a victim. He was truly a man, a warrior, one who knew how to die.

Hubbard always watched the warrior who was preparing to throw, and they succeeded each other so fast now that he was forced to be alert. His head had not moved since the beginning of the game. Any flinching, any twist to one side, would put his face in front of a whirling blade, and that would be the end. Perhaps such a fate would be best, for worse was to follow this sport, and there was no chance of rescue. But pride forbade resort to such a death.

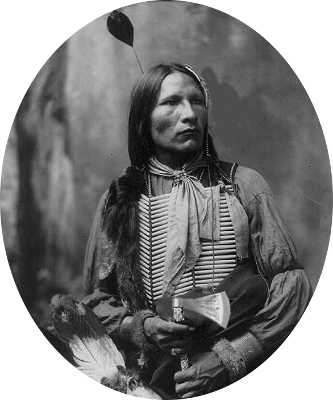

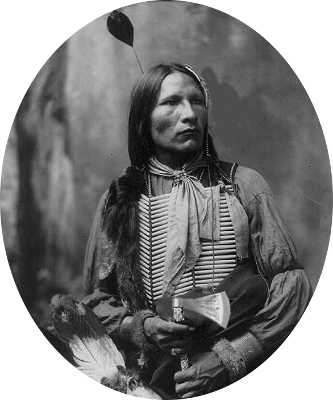

Black Feather’s fifth turn with the tomahawk came. He was a splendid tall fellow, with a black feather thrust through his scalp-lock, from which he took his name. Hubbard and he had been friends in a time when the white and red men were not at war; they had hunted together, and once Hubbard had saved him from the claws of a raging, wounded panther. But the white man did not count on that. He knew that such a thing as gratitude had no place in the Indian nature. Everybody said so, and, moreover, there was no chance for Black Feather to show gratitude had he wished to do it. So Hubbard redoubled his taunts when Black Feather stood before him, poising his tomahawk for a throw which should surpass all the rest. He told him that he was a coward, that he had known him in the days of old, that he would flee from a wounded deer, that the cry of a child frightened him, that he dreaded the darkness, that his wife beat him and made him hoe the corn while she went forth with the rifle to hunt for game. Had he come with the warriors to cook for them, or merely to clean the game that they killed? If he dared to go to the white settlements, one of the women would come out and whip him with switches.

Hubbard was surprised at his own skill and fluency. He surpassed himself. Black Feather made so fine a target that he felt as if he were inspired. Even the stoical warriors looked at each other. It seemed to some of them that the taunts had touched Black Feather to the quick. They marked a slight quiver in the hand that held the tomahawk aloft and a strange gleam in the warrior’s eyes, which looked straight into those of Hubbard. The hand flew back and the tomahawk whirled through the air. Hubbard saw the flash of light and heard the whiz of the speeding weapon. The next moment the blade was buried in the tree close to his side; the deerskin thong, severed in half, fell to the ground. The hunter sprang from the tree and rushed into the forest with a speed which soon left the disappointed band far behind.