Dan Mason’s Christmas

The soldiers were in a splendid humor. They had won a victory the week before and were now resting securely among the hills, with no prospect of hard duty for at least a month. All the scouts brought news that the enemy was continuing his retreat into the west, and, moreover, the weather did not invite to active service. There was nothing for the men to do but make themselves comfortable, and that they did the best they could.

They occupied a shallow basin in the crest of a low but very wide hill—a basin large enough to hold the entire army and seemingly intended by nature as a place of camp and defense. Their great guns made a ring around them and covered every point of approach. The soldiers felt that they could hold such a natural fortress against the assault of ten times their number, but they knew that an attack would not come, and they turned their minds to other things.

Nearly all the camp work was finished, and they were eating their suppers. Innumerable fires were burning, and the flames rose up in the clear, frosty air. Sparks flew off into the sky, trembled there a moment and then went out. The metal dishes rattled, and the hum of talk and laughter arose.

“This is comfort—solid comfort, I call it,” said Dan Mason, the Kentuckian, to his comrades, leaning back and luxuriating a little in the unusual rest and peace. The others did not reply, but devoted themselves body and soul to the food. Mason looked thoughtfully at them for a minute or two and then resumed his task. Yet he himself was worth the contemplation of any one.

Dan Mason, like his comrades, was young, but he was taller, larger and stronger that any of those who sat near him; a splendid specimen of the Kentuckian of the hills, a man of powerful muscles, open face and frank, brown eyes that looked straight at you, and yet at times would flame into a sudden passion that might prove dangerous.

“Isn’t this good, Tom Settle?” he said to the man immediately on his left.

“Of course it is,” replied Tom, with a sigh of content. “I like soldiering well enough, but I’m not such a glutton for it that I must have it every day in the year. A month of steady marches and battles and skirmishes before we came into these hills had just about finished me up. If there’s any fighting to be done before spring, Dan, you can have my share, and there won’t be any charge for it. Now you hear me talking.”

He resumed his attack upon the food, and the others laughed. It was in truth a most comfortable camp. The tents were raised already, and the men might take their ease without worry. Mason leaned back against a hillock and, drawing a tiny pamplet from an inside pocket of his faded army coat, studied it attentively. The others did not notice him for a minute or two, and then it was Settle who spoke:

“Reading, Dan?” he asked.

“Yes, Tom. I’m reading.”

“Is it so mighty interesting?”

“Yes.”

“Tell it, then.”

“I’ll let you know directly.”

Settle said no more. He was happy, and he would not allow even his curiosity to disturb him. Mason continued his study of the worn little pamphlet, his brow wrinkling now and then with a mental effort which evidently proceeded from an attempy to calculate something complex.

“Boys,” he asked presently, “what day in the week is this?”

“What funny questions you ask, Dan Mason!” exclaimed Settle. “How do you expect fellows who have been fighting for a month without a break to keep track of such little things as the days of the week?”

His pronouncement was received with approval by the majority, but a third man—Johnston—who took the question to heart, asserted that it was Friday, whereupon Settle, being compelled to return to the issue, staked his faith upon the day being Sunday. Johnston maintained that it was Friday, and both found supporters, while others held that it was neither Friday not Sunday, but were divided in choice between the remaining days of the week. Then a dispute arose and waxed hot. It was at its height when it occured to Settle to ask why they debated with such spirit a question that was unimportant.

“What difference, Dan, does it make what day of the week it is?” he said to Mason.

“It makes a lot,” replied Mason. “I want to tell you in the first place, boys, that this little book I’m studying so hard is an almanac. I’ve been keeping track of the days, and this is Saturday, and, what’s more than that, it’s the 24th of December. Now, Tom Settle, just you tell me what’s coming.”

Settle uttered a low whistle.

“Boys,” he exclaimed, “it’s Christmas night coming across yonder!”

There was a trace of awe in his tone as he pointed toward the east where the red sun was sinking and the had begun to gather on the horizon. A silence fell over the group and soon extended to the whole camp. Hardened by war, immersed in constant fighting and drawing a free breath this day for the first time in a month, these men had lost all track of time. So Mason’s sudden announcement came with all the greater force. Peaceful memories rushed upon them like a torrent, and the silence in the great camp endured. The minds of these men—boys most of them were in years, though old in experience—went back to other Christmas nights, when there was no thought of war and all was peace on earth and good will among men. They thought then of those who were left behind them, and they spoke softly and without oaths.

Lower sank the sun. It seemed ever after to Mason when he thought of that night that it was a globe of intense, molten fire. Its rays lay blood red on the hills, but the shadows continued to creep up nevertheless. It was gone by and by, and the east was in a darkness which soon extended to the four quarters of the heavens. Christmas night had begun, and the sentinels on their beats called, “All’s well!”

“Ought to be snow tonight. It’s Christmas,” said Settle.

“You have your wish,” replied Mason. “Didn’t you notice the clouds before the dark came? Here’s your snow.”

Settle looked at the heavens, and a broad flake settled upon his upturned face. It was followed by another, and then many more, and in five minutes they were falling down on the camp like a great white veil. The ground was soon covered, and the flakes continued to come down until the snow lay several inches deep. But it ceased by and by, and a clear silver moon shone in the cold, pale heavens. It was very beautiful to Mason, who had in his soul a little of the poetry of his native hills. This was the grace of God after a month of battle. He sat in the lee of a tent and looked at the white expanse of the earth and the dim line of the horizon.

The content of the soldiers did not decrease. It was a well sheletered and well provisioned army, and this was what they wished. The solemnity which they had felt at first began to wear away, and their spirits rose. The camp was filled with jest and laughter. Bright flames, flickering over the the snow, shot up from a hundred fires, and beside each some good story was told, The camp was luminous with light and good feeling.

A clear voice was uplifted presently, and some one began to sing. It was a song of Christmas:

It was a trained voice that sang, and presently others joined. The pure strain rose over the hushed camp, and the sentinels, walking back and forth in the snow, trod softly. More hymns followed, all that the soldiers knew, and then they sang the same over again. Mason listened for a long time, but by and by he arose and walked toward the outer edge of the camp.

“Good fellow, Mason,” said Settle, following the Kentuckian with his eyes, “but, like all the Kentuckians of the hills, he’s a powder flash when you touch him on a sore spot. I’d rather have any man than Dan Mason hunting me with his gun.”

“I ain’t got anything but cause to like him,” said Johnston. “I recollect how he took me off the field of Shiloh when I had that bullet through my leg and couldn’t walk. Didn’t seem to mind the bullets any more than he would hailstones.”

“He’s that way to his friends,” resumed Settle, who had grown talkative, “but it’s just as I tell you. He don’t love his enemies, and I don’t know whether a man ought to, either. Ever hear about the quarrel between him and Tom Markham over a girl just before the war came on? Markham lived close by, and it was hot between ’em. They say Markham wasn’t fair—played some low down trick—I don’t know exactly what it was, for the war began just then, and Dan and I came away to it, while Markham joined the other side.”

The others bent their heads nearer, eager to listen to a good story, while Settle proceeded with further details. Mason continued his walk meanwhile to the farthest edge of the camp. His mind had gone back to the same story that Settle was telling. He was thinking of Markham and of the girl over whom they had quarreled. The hot blood leaped to his head, and, clinching his fist, he shook it in the darkness. Had Johnston seen him then he would have felt the truth of Settle’s words that Mason was not a man who “loved his enemies.”

In truth, it was never part of Mason’s code to love his enemies. It had been taught to him in his native mountains to exact an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. Even now, as he thought of Markham and the great wrong that he had suffered from him, he longed for the time where the war would end and he might seek his revenge. He bore no animosity toward the soldiers on the other side except this particular one—Markham. He fought the others from a sense of duty, and, the war over, he could be good friends with them. But there could be no forgiveness for Markham. Again he clinched his hand and shook it in the darkness. His sense of the wrong done him was as keen as ever. Two years of incessant campaigning had not diminished it, and when the excitement and danger of each great battle were over he found that the memory of it would come back to him as strong as before.

Mason stood at the northern rim of the camp. The sentinel who walked the beat there was a friend of his and nodded at him as he passed. The moon shone brighter and clearer than ever in the cloudless skies, and Mason, looking back at the camp, saw it brilliant with many lights. Clear and sweet still came the words of the hymn:

Then the song ceased suddenly as a half dozen rifle shots rang boldly in the night air. Mason stopped quite still, and all his thoughts passed abruptly from peace to war. He looked forward toward another hill, divided by a shallow but wide valley from the one on which the camp lay—a hill on which clusters of bushes grew here and there, affording a cover for daring riflemen. He had marked the place from the first and noted what a good cover it would be for annoying sharpshooters if the enemy were not fifty miles away. Now it seemed that at last some skirmishers were not as much as a mile away. While he looked he saw some jets of flames from the bushes and heard the crack of three or four more rifle shots.

“Join these men, Mason,” said an officer, “and clear those skirmishers out of the bushes. It ought to have been done before we settled into the camp. A picket of ours should be there now.”

But Mason did not wait to hear the officer’s grumbling. He went mechanically about the business upon which he had been ordered, shouldering his rifle and falling in with the party of twenty who were to clear the bushes. He was a good man for such work, a master of woodcraft, cool, cautious and afraid of nothing.

The disturbance in the camp was only momentary. The soldiers were accustomed to such trifles. A few rifle shots fired from ambush could not annoy for more than five minutes men who had gone through many great battles. Nor did the thought of his task lay heavy upon the mind of Mason. Accustomed to such duties, he would perform it presently and return to his place with his comrades. It was merely mechanical.

They made a wide circuit around the valley and approached the hostile hill from the rear. Then they lay close to the earth and listened for sounds of their enemies, but they heard none—only the distant hum of their own camp and the notes of a Christmas hymn rising in the cold night.

“We’d better separate here and surround them,” said the commander of the little troop. And the men spread out like a fan, Mason taking his way up a little gully. He was creeping on hands and knees like an Indian. All the instincts of the Kentuckian of the mountains were aroused in him. The flame was in his blood, and he was now the hunter after prey.

Forward he went, searching the interlacing bushes with his keen eyes, his rifle at the cock and every muscle tense and ready for action. His stained and dark uniform would have made a blot on the snow, but he kept to the cover of the bushes, and no one looking there would have known that a man was passing.

He could hear the notes of the Christmas hymn swelling in a chorus of many voices, but it was unheeded. Mason now had work to do, and he meant to do it. He crept up the ravine and near the hill stopped and listened intently. He thought that he heard a soft crunch on the snow, as of some one moving behind a thick clump of bushes that grew near, but he was not sure whether it was a friend or an enemy. He approached a little, lying down on the snow, and drew himself forward with body outstretched like a snake. He heard the sound again, very faint now—so faint that it would have passed unnoticed by any ear less keen than his own.

Mason felt that it was an enemy behind the bushes–an enemy who knew that danger was approaching and would be cautious. His blood swelled with the pride of conflict and the emulation of skill. He would watch this wary foe, and his muscles became tenser than ever as he prepared for the test. He glanced only once at his rifle to see that the weapon was ready and then resumed his sliding and slow advance. He reached the clump of bushes and, laying his ear to the snow, could hear nothing. But he was confident that his foe was still on the other side. He could not have escaped unseen, and, sure alike in his courage and his judgement, he began to creep around the bushes, his finger on the trigger, ready to fire at the first glimpse. He reached the other side, but nothing was there—only a trail in the snow to show how his enemy, too, had made the circuit—and the bushes still stood between.

But Mason was not discouraged. He did not expect to catch the man without trouble. The unknown would have been a very cheap sharpshooter indeed if he had allowed himself to be overtaken so easily, and Mason felt pleased because the enemy matched against his skill and courage seemed altogether worthy of him.

He began the second circuit of the bushes, more careful now that ever, not making the slightest noise, lest his enemy should hear and take warning. When he was half way around, the sound of shots to both left and right rose, and he knew that his comrades were in battle with the other sharpshooters. But they were too far away to be seen, and he did not take his mind from his own particular part of the work. It was one of the merits of Mason that he knew how to attend to his own business.

He was as patient now as the Indians whom he imitated, creeping forward and then turning back, seeking to entrap his wary foe. But the man seemed to return with him every time and still remained hidden. Mason could not tell whether his enemy was endeavoring to escape or pursue. He laughed noiselessly at the thought that he himself might be pursued while he was pursuing. Well, it did not matter. It merely made the test of skill all the more interesting.

He heard the notes of the music again, louder and clearer than ever, and then more rifle shots. The skirmish was flaring into increased activity. He listened to it for a moment, although he never doubted that his comrades would win, But he trusted that they would not win too soon, as he wished to finish his own affair without help.

Then he turned suddenly and went swiftly back on his own track, catching a glimpse of a dark figure around the curve of the bushes. He raised his rifle and fired, but not quicker than the other man. The reports were simultaneous, and a bullet clipped the clothing on Mason’s shoulder. Whether his enemy was struck or not he did not know, and there was no sound.

Mason was annoyed. He must devise some method of finishing it quickly. He lay quite still and pondered deeply for a minute or two. Then an idea came to him. He took off his cap, placed it on the end of his gun barrel and, laying flat, thrust it out in front of him, raising it slightly in the air. He made no mistake. There was a flash, a report, and a bullet whistled through the cap. Spiriting to his feet, loaded rifle in hand, he ran forward.

His enemy, trapped so neatly, leaped up, his empty rifle still smoking at the muzzle, and ran through the thickets. Mason followed fast. The passion of the chase was upon him, and he resolved that the man should not escape. He raised his rifle once and marked a spot on the fugitive’s back where he could plant a bullet. But he did not like to do it. He would rather shoot him in a fight, face to face.

The man as he ran made desparate efforts to reload his rifle, but failed. Presently he threw it away, as if he feared that it would impede his flight. Then he ran faster. But Mason, too, increased his speed. The despairing fugitive heard the crunching footsteps on the snow moving closer and closer.

They reached a little glen, and here the fugitive sank down among some bushes, exhausted.

“Throw up your hands!” cried Mason, raising his rifle.

The man raised his hands, saying, “I yield!”

But Mason did not lower his rifle.

“Yes, you yield,” he said, “but I don’t know that I ought to spare you. I have my opinion of a man who sneaks up to a camp in the dark and shoots from ambush.”

“It’s war,” replied the man.

“I suppose it’s allowed,” said Mason meditatively, “but if the say so was mine every man who does so would get a bullet. I don’t like this sharpshooting, anyway. There’s too much sneaking business about it.”

The glen in which they stood was shaded by the forests and thickets, and only a little light filtered through the branches. The sounds of the combat elsewhere had died, the fighting evidently finished. They could not hear the noises of the camp—only the sounds of the Christmas song.

“You led me a long chase around that thicket,” said Mason, laughing a little. “Three or four times I thought I had you before I worked that cap trick on you.”

“And three or four times I thought I had you,” replied the man.

“Maybe so,” replied Mason, who was too polite to dispute his assertion. Yet he was sure that it was his skill and not his luck which had achieved the victory. He noticed now that the man still remained on his knees in the snow. He seemed to be dreading a blow.

“Get up,” said Mason. “Of course when I was talking about sharpshooters I didn’t mean to practice what I was preaching. I’m going to take you a prisoner to camp, and I dare say they’ll treat you well. Come on.”

The man did not rise. He crouched even lower in the snow. Mason bent down to put his hand upon his shoulder and jerk him to his feet, but he started back before his fingers touched the kneeling figure.

“Why, you are in our uniform!” he cried, “What does it mean—a spy?” The man shivered.

Don’t take me to your camp!“ he cried. ”Before God I swear that I’m no spy. I’m just a skirmisher. I put on the uniform thinking it would be easier for me to get away if I was pursued by your troops. I swear that it’s true! I just meant to trick you!”

Mason did not believe him. He thought the tale most flimsy, and at the moment he felt little sympathy for the man. War had hardened him, and, like most soldiers, he had no pity for spies. He accepted the decree that all such should be hanged or shot when caught, and considered his prisoner a criminal whom he must take to justice. He looked at the dim figure of the kneeling man, and then he said:

“What you say may be so, but they’ll hang you as sure as my name is Dan Mason.”

The man sprang to his feet and ran. But Mason leveled his rifle, calling to him to stop or he would fire, and he added by way of precaution that he could not miss so good a target. The man sank down again in the snow, uttering a despairing cry, and Mason stood over him once more, still holding his rifle for use if needed. They were out of the shadows now, and the moonlight fell upon the face of the captive. Mason saw his features for the first time, and when he looked he uttered no threat, no exclamation, but stood perfectly still for a moment, his face turning deadly pale. Then he lifted his rifle again.

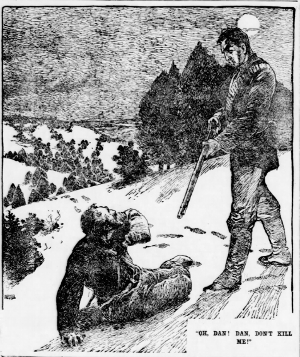

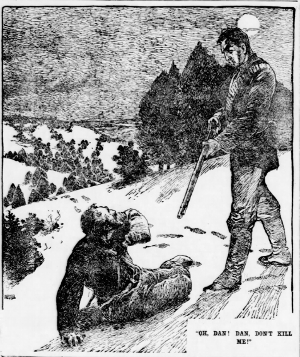

“Oh, Dan! Dan, don’t kill me!” cried the man, falling at his feet in terror and grasping the snow in his hands.

Mason’s body was rigid. Only the fingers of his right hand moved, and they played restlessly with the trigger of his rifle. He looked straight at the abject figure kneeling before him. He thrilled with powerful emotions, and triumph was strongest among them. His enemy was delivered into his hands. God was good and intended to see that he secured his just revenge. How could he doubt it when he looked at the face before him?

“Why shouldn’t I kill you, Tom Markham?” he asked. “Would you spare me if it was the other way?”

“Of course I would!” You know I would, Dan!“ replied Markham.

“You lie!” said Mason. “If you had a chance, you would shoot me like a dog.

“You have been a liar and a sneak all your life. Who should know better than I do?” Mason’s figure was still rigidly erect, only the finger that strayed so restlessly over the trigger of his rifle moving.

“Yes, it’s so, Dan,” cried Markham, “but this war will be over some day, and then you can go home, and you’ll have another chance.”

“I don’t know about that,” said Mason grimly. “I may be dead when the war is over. But at any rate you’ll never go back to tell any more lies about me.”

“It would be murder, Dan! You know it would be to kill me now, when I’m unarmed!” cried Markham.

“What right has a hound like you to talk of murder?” said Mason. I’ll be making the world to put you out of it. Besides, I’d only ridding the officers of a dirty job. You’re a spy, Tom Markham, and according to the laws of war, you’re to be put to death. I send a bullet through your head, and the thing is done neat and quick.”

He stepped back a little and cocked his rifle. The man threw up his hands again and begged for mercy. Standing farther away now, Mason could scarcely see his face. The moon was hidden now by a drifting cloud, and the shadows had come over the glen. There was no sound in the woods about them. His comrades had returned to the camp, having finished their part of the task. He looked up at the hill where the army lay. It was bright with many lights, and now and then he saw a dark tracery appear upon its luminous shield. He knew that it was the soldiers passing between him and the fires. He would be back with them soon, and there would be one scoundrel less in the world. There was satisfaction in the thought that his own hand would achieve the good work. The fierce mountain blood was hot in his veins and called for the death atonement upon the man who had done him a wrong.

The hymn had died for a little while, but now it rose again, borne aloft by a hundred voices, louder, clearer than ever and filling the night with melody. All other sounds were hushed at the distance. It alone sounded in the ears of the two men—the one who knelt and begged for mercy and the one who stood over him, cocked rifle in hand. That same sense of awe which he had felt earlier in the evening and then had shaken off began to steal over Mason again.

“Dan! Dan! Do you hear that?” suddenly cried the man.

“Yes, I hear it.”

“Do you know what it means?”

“Yes; it is Christmas night. You need not tell me that. I know it. What have you or the likes of you to do with such a night as this?”

Markham looked up into his face.

“It’s not me, Dan; it’s you that ought to think about it,” he said. “It’s murder, Dan, if you kill me—me an unarmed man. And think of it, Dan, on such a night as this—Christmas night, with that song ringing in your ears. Whenever you lay down to sleep, you’ll hear it again.”

The note penetrated all the woods and seemed to Mason to increase in fullness. It annoyed him. He wished they would stop. There had been enough of such sentiment. He was not a weak child to be turned away from his just revenge. He was merely the executioner whom this criminal deserved.

“Say your prayers, if you know any to say,” he exclaimed roughly. Your time’s short, and it’s going fast.”

“Dan, Dan, you won’t do it!”

“I will.”

“Listen how they sing, Dan! Are you any better than they are? This is the night that a man ought to forgive his enemies. You wouldn’t murder me on this of all nights in the year! Remember, Dan, that we were friends once. You won’t forget that, will you?”

“You forgot it,” said Mason.

He looked again at the kneeling figure and thought how he had longed more than two years for this moment. He had often pictured it to himself and had imagined in advance the joy which now he did not feel. How could he with the words of that song ringing in his ears? If it were only any other night!

“It’s not murder; it’s a punishment,” he said at last.

“Don’t kill me, Dan!” said the man. “Take me a prisoner to the camp.”

“And if I do,” replied Mason shortly, “they’ll hang you for a spy. Don’t forget that.”

Markham was silent.

The song did not cease. It seemed now to Mason that it was addressed to him alone. Would it be murder, and not a punishment, as Markham said? What would he think of himself in the morning? Could he return to the campfires and sit calmly by his comrades, singing of Christmas night?

“Dan!” said the man.

Mason did not answer.

The song swelled into a great volume of sound, filling all the woods and echoing about them.

Mason felt that it was calling to him, and he could not refuse to listen if he would.

“Goodby,” he said.

He turned about suddenly, leaving the kneeling man in the glen and, putting his rifle on his shoulder, walked back to camp, while over his head rolled the words of the hymn: