10 The Test of Steel

Guthrie would have slept late the next morning had it not been for the call of his hostess to breakfast, set for a certain hour, at which time all must come or go without. His first inquiry was for the Senator. What had become of him, and what was he going to do? Mr. Pike was to preach the funeral sermon of his brother, and the woman pointed to the low log church just at the base of the mountain.

Guthrie felt again a deep thrill of sympathy for this man who was trying so hard to lead an enlightened life, but whom association and circumstance tried in so fiery a crucible. “Where does Mr. Pike live?” he asked, and they pointed out to him a large frame house, standing near the creek. It was the only one in the place not of logs, and Guthrie had not observed it the night before. The immediate impression it made was of superiority to its surroundings, just as he knew that its owner had raised himself above the people among whom he was born.

Guthrie, acting upon his impulse of sympathy, approached the house, and noticing that others were entering the door, fell in with the crowd after the mountain custom and passed inside. The people with whom he went included both men and women all with the mountain stamp upon their faces, and all solemn and gloomy. Some of the women were crying.

Mr. Pike stood at the door of a large room in the centre of which rested the coffin of his brother. The Senator’s face was pale, but his features were firm and composed, and his long, black frock coat was buttoned tightly about his body. He shook hands with the people one by one, and, when he came to Guthrie, he said simply, “I am glad that you are here, Mr. Guthrie, to share our grief.”

Guthrie, by the necessity of his career, had become familiar with scenes of sorrow, and he had looked many times upon the victims of violent death; but none stirred him more deeply than this gathering of the rude mountaineers about their dead. Scarcely a word was said. He heard only the moving of feet and the soft crying of the women.

Four men lifted the coffin presently, and bore it from the house toward the church. The Senator followed, bare-headed, and just behind and after him came the people in double file—a procession of mourners. Guthrie fell into line beside a young mountaineer, and hat in hand followed on.

The day was not like its predecessor; the sun no longer gilded the mountains; instead heavy, leaden clouds were trooping up from the southwest. Guthrie felt once the touch of a wet snowflake on his face.

The solemn procession entered the church, and the coffin, the body within, was placed at the foot of the pulpit. The people sat on the rude wooden benches, filling them to the last seat. Then the Senator ascended the pulpit, and preached the funeral sermon of his brother.

Mr. Pike was not a regularly ordained minister, but he possessed the gift of eloquence, and, in the mountains, where religion fills so large a share of discussion, he often preached. The secret of his great power over these people, as Guthrie saw, lay in his superiority of character and culture, his readiness of speech, and his capacity for the happy phrase. He had, in this moment of grief and tension, a rapt and solemn air as of one who is an interpreter between this world and the next

Mr. Pike spoke of the hereafter as a place of safety and rest—the simile was inevitable in the mountains where vigilance was the best guard against danger—and he described our path in this life as beset with thorns. Short were the days of man and full of sorrow! It was only in the hereafter that joy true and lasting came. Then he spoke simply of his brother, so many years younger than himself—who had always been but a boy to him—and of his sudden end—without a moment’s warning! He made no threats against those who had slain his brother—he never called their names; but through all his sermon ran an indefinable note which seemed to say, “Vengeance is the Lord’s—but man may be his instrument,” and Guthrie knew that Mr. Pike felt in his heart he was “the man.”

The Senator talked on. All hung on his words. These were his people, and he swayed them alike as he inclined to vengeance or to the blessings of the hereafter. Guthrie, too, followed, both his sympathy and his interest keeping him intent upon every sentence that fell from the speaker’s lips. Once he glanced through the window, and saw that clouds darker and heavier than ever were filing in solemn procession across the sky. Now and then a snowflake struck the glass, and the wall of the mountain looked black and threatening.

The quality in the speaker’s sermon that seemed to indicate the note of vengeance appeared again, and Guthrie saw its effect on the faces of the audience which grew black and lowering; but in a moment Mr. Pike shifted to the peace of the hereafter, and in another minute or two closed. Then he made a short prayer touching in its simplicity and pathos, and descended from the pulpit.

The solemn procession began its march again, and passed out of the church to the foot of the mountain where the burial took place; after which the crowd dispersed slowly, leaving the Senator and Guthrie together. Guthrie knew that they burned with curiosity about him, and later would ask him questions, especially as they saw that Mr. Pike and he were friends. However, for the present, they let him alone.

The Senator stood a little while beside the freshly-turned earth as if in silent prayer, and then turning away put on his hat, and held out his hand to Guthrie.

“Mr. Guthrie,” he said, “I did not want you to come, but since you are here, I am glad of it. Somehow, you seem to me to represent that other world beyond the mountains, and, in your person, it mourns beside my brother’s grave. I thank you.”

Guthrie gave the Senator’s hand a sympathetic clasp, and then the two walked together among the trees. He saw that Mr. Pike must speak to some one, must find somewhere an outlet for his feelings, and he listened in silence and sympathy. A secret of his popularity with men of influence and power was this ability to listen well.

The Senator talked of his brother and himself, of the mountains and the world beyond, and Guthrie listened, absorbed. Both forgot the clouds and the falling snow. The flakes fell faster and larger. Already the new grave behind them was covered, and, had they looked to see, they would have found that the crests of the peaks and the ridges were lost in the mists. The damp winds from the southwest came on a front of snow.

But neither Guthrie nor the Senator yet noticed. The stoicism of the mountaineer in this moment of grief and in the company of the warm, human sympathy that Guthrie gave him was broken at last. He told how he had struggled to stop the feud, how he had tried to rise above the feelings of passion and revenge, and to train his people also to set their minds on higher objects. He was borne up, there in the capital, by the comradeship and friendship of men who had seen more of the world than he, and he had believed that, through his efforts, peace would last in his part of the mountains. Then came messengers telling of threatened trouble, and informing him that the Dilgers would seek to renew the strife. He had not believed, he had looked upon it as a false alarm, and the messages were renewed, more emphatic than ever; then came the news of his brother’s death, and he had tried to endure it like a Christian man, preaching Christian resignation to himself.

This and much more he poured forth, often disjointed or half-finished, but as clear as water to Guthrie. He saw the dual nature struggling in the man—the old mountain doctrine, an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, the inheritance of birth, and through all the years of his boyhood deemed a matter of course, and the new principles of peace learned in manhood. He was now face to face with the most powerful test, and Guthrie thrilled once more with sympathy for this man whom he liked so much, and to whom fate had been so unkind.

Their walk led them far into the forest, which extended along the base of the mountains, a wood of tall oak and beech with a dense growth of underbrush. The two men followed a path which seemed to be fairly well-trodden like a mountain trail. Guthrie looked up, and was surprised to find the boughs covered with snow. The skies cleared for the moment, and shone in vivid blue; beneath this, the trees veiled in snow were cones of white. The forest was silent, save for the occasional soft drop of snow or the cracking of a dry branch under its weight. The air once more was pure and fresh.

Guthrie looked back, and the hamlet was lost among the trees. The two, absorbed, the one in talk and the other in listening, had passed deep into the forest. To all intents, it was still the primeval wilderness in its winter robe of white. Save themselves there was no sign of a human being or a human habitation. All around them under the trees stretched the snow, white and untrodden. Seemingly the world was wrapped in a great peace—but it was only for a moment.

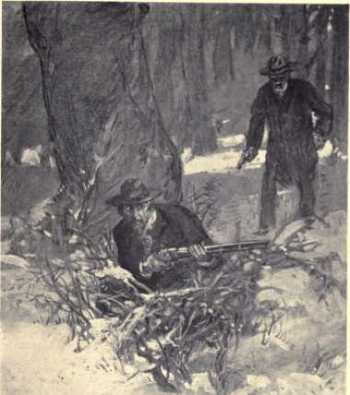

The Senator suddenly grasped Guthrie by the arm and exclaimed, “Did you not hear a footstep?” But Guthrie heard nothing; the forest ear was more acute than his. The next instant, the hand of the Senator tightened on his arm, and he was dragged down in the snow. Then he heard a sharp report that sounded to him like the cracking of a great whip, and a buzz as of something passing with lightning speed over their heads. He looked up and saw a brown, evil face, fifty yards away thrust from behind a tree-trunk, and a pair of brown hands lowering a rifle barrel. He heard the Senator exclaim, “Pete Dilger!” and he sprang to his feet. He knew from what he had heard in the village that Pete Dilger was the worst of all the Dilgers.

The Senator was up before him, and Guthrie was stunned by the change in his friend. Every trace of the civilised man had disappeared from his face. He was crouched like an Indian in ambush, and a huge self-acting revolver was held in his right hand. The high and sharp cheek-bones looked higher and sharper than ever, and the cruel black eyes glittered with the passion and joy of revenge. His hat had fallen off, and the long, straight black hair, sweeping back from his brow, continued the likeness of the Indian.

But, even in this tense moment, the man was not forgetful of his friend. Sweeping Guthrie back with his left hand, he cried: “Go back! You have nothing to do with this!” Then he ran into the forest, directly toward the point where the ambushed marksman had lain, and Guthrie caught a glimpse of Dilger seeking a new place of concealment. Then the trees shut both from his view, and he was alone.

Guthrie stood on the spot where the Senator, foreseeing the shot, had pulled him down. The paralysis of the moment passed, and he tried to choose a course. He had no doubt that the Dilgers now identified him as a Pike follower, because he was in the company of Mr. Pike. The Senator was right when he had told him to stay away.

Guthrie had all an enlightened man’s horror of strife and bloodshed, but he thought nothing then of the way that he had suddenly been projected into this mountain feud. All his thoughts were of the Senator. Would there be a duel between him and Dilger, or would Dilger lead him into an ambush? He was tempted for the moment, to follow them by their tracks in the snow, but that would be folly in an unarmed man, and he obeyed his second impulse to hurry to the village and secure help for the Senator. He did not realise in the moment of excitement and suspense that he had become an ally of the Pikes, nor would he have stopped, had he realised it.

He ran a few steps, and then he stopped again. Unarmed though he was, he could not leave the Senator alone in a struggle! even if he procured help in the village, all would be over before he could arrive. He looked about him, and saw again the world in white—the world of mid-winter, deep, still, and cold, but a cold that sent the blood leaping through the veins, cleared the brain, and doubled the strength of every nerve and muscle.

Hills and valleys were covered with snow, soiled by no human foot. There was no sound in the forest save the crack of some bough breaking beneath the load of snow.

Guthrie stood at his full height, and inhaled deep draughts of the cold, pure air, feeling that he was a strong man in a world of strong men and could care for himself. A bough fifty yards away broke with a crack louder than the rest, and its weight of snow fell with a soft, crushing sound.

He saw a heavy stick lying at his feet, and he stooped to pick it up for lack of a better weapon. Again he did not realise that some of his own civilisation was slipping from him, and he was becoming the hunter—the hunter of men.

As he bent down to pick up the stick, he heard a slight noise, and his eyes wandered around the circle of the horizon until they reached a clump of bushes on his right. There they stopped, and the hand that held the club remained suspended in the air.

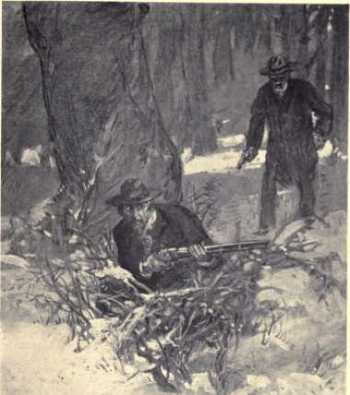

The surprise was so sudden, so terrible, that Guthrie felt for an instant as if his veins had become empty of blood and he were a lifeless thing. He took only one brief glance, but he saw distinctly every feature of Dilger—the leathern face, the black, exultant eyes, and above all the rifle held in steady hands. He knew that Dilger took him for an ally of the Pikes. And what else was he now? He was at the mercy of a merciless man.

Guthrie, by a supreme effort, recovered command of himself. One glance at the cruel, taunting face had shown him that the mountaineer, with the instincts of the savage would wish to enjoy his triumph, to play a few moments with his victim before sending the fatal bullet. So he pretended not to see, and sinking to his knees began to brush the snow off the stick. Perhaps the Senator might come! Mr. Pike might save him; it was a faint chance, the shred of a hope, rather; but the soul of Guthrie clung desperately to it.

His eyes, in spite of himself and his will, wandered from the stick, and were dazzled by the flood that the sun poured over the snow. The world, tantalising him, suddenly grew brighter. There was a new and deeper tint of blue in the sky; the snow gleamed like marble; countless silver rays flashed from the slopes.

Guthrie went on mechanically with his task, but his brain grew dizzy. The world was in a whirl. His mind ran back through the dim, discoloured mist that is called the past, and then tried to enter the future. But, out of the vagueness, rose one fact, clear and distinct, and it was the knowledge that he wanted to live.

He cast a glance from under his bent brows at the mountaineer and saw him still standing there at the edge of the thicket with his rifle levelled, savage, implacable, never dreaming of mercy.

Another swift glance, and he saw a figure appear in the forest on the left, a tall man wrapped in a long black coat—the Senator. He knew that Dilger, intent upon his victim, had missed the approach of his real enemy. But the Senator, the skilful and wary, would see, and Guthrie waited. The faint hope, that was scarcely a hope, sprang up.

Would he be in time? If only fate would give him ten seconds! If not that, five! Five would be enough, but the Senator might miss, even if he were first! But that was impossible! He ought not to wrong his faithful comrade so.

He longed to look up again, but he dared not glance at either mountaineer. He could not know which finger was nearer the trigger, but he must await, as if in unconcern, that second of difference which meant life or death to him. Nothing that he could do would alter the future by a hair.

The whiteness and glitter of the world dazzled him. The hand that held the stick became wet. He affected carelessness, and began to hum a song, unconscious of the words he spoke. He grew impatient. Better the bullet of the wrong man than to endure this terrible tension! There was still not a sound in the forest. The snow had ceased to fall from the boughs. He did not hear his own breathing.

His muscles seemed to relax, to give way. His head bent lower. He was afraid that he would fall.

The report of a pistol and a cry so close together that they seemed one, rang in his ears, and, with a wild shout of relief, excitement, and joy, his face white to the brow, Guthric sprang to his feet as the Senator, a smoking revolver in his hand, ran forward.

The relief from the tension and the expectation of death was so great that Guthrie stood for a few moments white and dizzy. Then, mechanically, he wiped the sweat from his face.

He was aroused from his stupor by the sight of Mr. Pike bent over the fallen man, every line of his face expressing the thought, “O, mine enemy, thou art delivered into my hands!”

Dilger was not dead. Guthrie could see that he was merely stunned by the bullet, as his chest rose and fell with almost regular motion, but his gaze wandered away from the face of the desperado to that of the Senator. Mr. Pike, too, was still the Indian—the garment of civilisation was yet doffed. Beneath his hand lay his mortal enemy, and all his mountain code, imbibed with the milk that he had drawn from his mother’s breast, told him to fire again.

Guthrie was still under the spell. He had been fascinated when he saw the muzzle of a rifle aimed at himself, and now he was motionless when he beheld the finger of Mr. Pike creep toward the trigger of his revolver.

Dilger lay prone and relaxed, and the blood from his wound soaked redly in the snow. Guthrie wondered where the second bullet would strike, and then he saw the muzzle of the Senator’s pistol cover the man’s heart. Like Dilger, the victor would enjoy for a moment his triumph.

The fallen man stirred, opened his eyes, and looked up. A gleam of intelligence appeared on his face as his gaze met that of his triumphant enemy, and then it became full of malignant ferocity. He was the savage still, asking no mercy, expressing only hate.

“I sent your brother on before,” he said in tones feeble but defiant.

The eyes of the Senator flashed, and his finger touched the trigger. Guthrie at that moment remembered, and the fire of the hunter died within him; all his instincts rebelled at what he was about to see.

“Mr. Pike,” he exclaimed, “you cannot kill a man who is lying at your mercy!”

“He is a murderer—you heard him—and the enemy of my people!”

But Guthrie had the gift of boldness and eloquence in great emergencies, and now he rose to the crisis. He seized the Senator’s uplifted arm, and turned the pistol away; he bade him remember who and what he was, a leader of his people, one who should set to them a great example. The Senator strove to raise the pistol again, put Guthrie held his wrist with a firm hand, and he saw the whole struggle written upon the man’s face as it passed in his mind. The old elemental impulse to kill the enemy who sought to kill him was strong within him; but the voice of a severer and better world of duty was calling in the voice of this friend, who had shared his danger and bade him to remember the new teaching. Guthrie struck the right chord when he appealed to his religion, and the second half of the mountaineer’s dual nature, his humble piety, rose in the ascendant. Gradually the flame of passion died in the Senator’s eyes, and at last he put the pistol in his pocket, and said to Guthrie:

“You do not know how much you are asking of me!”

“I can guess,” replied Guthrie. “He is a murderer, and should be hanged; but let it be done by law.”

“Yes, he shall hang,” said the Senator fiercely, “if there is justice to be had in the mountains!”

Dilger raised himself on his elbow—they had taken away his weapons—and was gazing wonderingly at his enemy, as if he could not understand his action—and perhaps he could not—but the Senator with folded arms and melancholy eyes merely gazed down at him.

Guthrie suggested that he go to the town for help while Mr. Pike remain on guard, and, as the other nodded assent, he hastened away in the snow, but he looked back once, and saw the erect, black-clothed, and melancholy figure still standing by the fallen man.

Much of Guthrie’s excitement slipped from him as he went on. The tenseness of those moments back there had been too great to last, and once more he looked with a seeing eye at the forests, the mountains, and the sky. The snow had fallen again, and the stillness of old reigned in the forest. He no longer saw a human being nor heard the sound of a footstep save his own. The scene back there might have been the phantasy of a moment, but its impression was too deep, too vivid, to pass, and he hastened on to the village.

When he returned with help, they found Dilger still on his elbow, and the Senator yet standing over him, silent and sombre. Great was the surprise of the people to find the leader of the Pikes, with the power of vengeance upon his worst enemy in his hand, and as yet unused; and mingled with this surprise was a strain by no means of approval. What had come upon the Senator? Had he lost a part of his courage? After all, was he fit for leadership? Guthrie remembered those words of the Senator’s, “You do not know how much you are asking of me!” and their truth struck home. The chief had fallen a notch in the opinion of his people.

But they took up Dilger, and carried him to the village. His wound was not serious, the mountain doctor said, and they locked him in the little log jail, to await his trial for murder. But Guthrie, as he went about the place, soon saw that other plans were afoot. They were all Pikes in Briarton, and their leader, they said, should have shot Dilger down when he had the chance; since he had not done so—well, they could supply the want of forethought; they knew too much to wait on a long trial, the testimony of perjured witnesses, and the innumerable delays that the law knows how to invent. Guthrie saw before him all the elements of a lynching, but these elements were not yet gathered into an aggressive whole, and swift action might prevent it. As there was no one but himself to take the initiative, he resolved to act.

First, however, he would see the Senator, and he went to his house. Alone in the large room where the body of his brother had rested, he found him sitting—staring out at the mountain side but not seeing it. To Guthrie’s great surprise, his whole attitude was that of one crushed; there was no triumph over the capture of his foe, but the droop of one who had failed.

Guthrie, feeling that he was in a sense the intimate friend and associate of the Senator, went up to him, and touched him on the shoulder. The older man raised his pale face.

“Mr. Guthrie,” he said, and there was pathos in his voice, “you see me in my shame. I have tried to be a man. I told you once before how I have sought to raise myself above the surroundings amid which I was born—to make myself a leader among my people, a real leader, not one who goes the way they wish him to go, but the way he thinks they ought to go.”

“And it seems to me that you are such,” said Guthrie. “I do not see wherein you have failed.”

“Out there in the forest I failed; when Dilger lay at my mercy, I would have killed him, not from motives of justice, but from revenge. Everything that I have schooled myself for twenty years to learn was swept away by the impulse of a moment. Had you not been there, I should not have held my hand; we are weak clay, Mr. Guthrie!”

Guthrie felt much sorrow, as he liked Mr. Pike and gave him his full esteem. He knew no man whom he held more highly, but, for a few moments, he said nothing, looking out of the window at the snow that was still falling. Then he glanced at Mr. Pike who had settled back in his chair, his whole figure expressive of apathy. He must be roused to action, thought Guthrie, and he spoke to him again. He told him of his fears, of the talk of a lynching, and he appealed to Mr. Pike’s pride. A flash appeared in the Senator’s eyes when he heard the news, and his figure swelled anew with life.

“That I will stop!” he exclaimed; “I did not spare Dilger to have them lynch him. My people are against me now; well, I shall give them cause!”

But Guthrie even knew better than the Senator how much he had lost in authority, and, though he did not believe he could prevent what the people in the village were meditating, yet he deemed worth while, for the Senator’s own sake, that he should try.

He saw the Senator, as he sought to persuade the people, feel all the pride of having done a right deed. The revulsion had come, and once more he was the civilised man striving for the better path. But Guthrie noted how little Mr. Pike’s words affected them, how the vengeful faces did not change, and, long before nightfall, a messenger, heavily paid, was riding over the mountains to Sayville, bearing Guthrie’s report of the news and a brief despatch to Governor Hastings, also signed by him and saying, “The leader of the Dilgers is in jail here, and will be lynched unless the militia come at once.”

Throughout that night which was dark and lowering, with a raw wind off the peaks, the people were quiet, but the next morning they began to gather again, having received fresh recruits from the surrounding country. Guthrie feared that the explosion would come at once, but then the snow began to fall, not as before slowly and lazily, but in great flakes that trod upon each other heels—so fast they came. Never before had he seen such a day. The sky was rimmed in with heavy, threatening clouds through which the sun shone with only a faint coppery tint, as if it were the faint reflection of a great fire, and, from these clouds, the snow poured and poured until the last trace of the sun was lost, and there was left only the brown sky above and the white world below.

The snow stopped never for a moment during the day nor during the night that followed, seeming rather to increase in volume, and the next day it was still coming down as fast as ever. The people, forgetting the lynching, huddled in their houses, and Guthrie, at Mr. Pike’s, looked out aghast. His messenger had not come back from Sayville—he could not; the snow already lay three feet deep on the levels and untold feet in the clefts and the ravines, and nowhere was there a break in the great white fall.

Day followed day, and the snow still heaped up around Sayville, and the imprisoned Guthrie raged at the thought of the capital and the trial of Carton now at hand, and he far away.