7 His Greatest Speech

It was the candidate’s eighth speech that day, but Harley, who was in analytical mood, could see no decrease either in his energy or spontaneity of thought and expression. The words still came with the old dash and the old power, and the audience always hung upon them, the applause invariably rising like the rattle of rifle-fire. They had started at daylight, hurrying across the monotonous Western plains, in a dusty and uncomfortable car, stopping for a half-hour speech here, then racing for another at a second little village, and then a third race and a third speech, and so on. Nor was this the first day of such labors; it had been so week after week, and always it lasted through the day and far into the darkness, sometimes after midnight. But there was no sign to tell of it on the face of the candidate, save a slight redness around the edge of the eyelids, and a little hoarseness between the speeches when he talked to his friends in an ordinary tone.

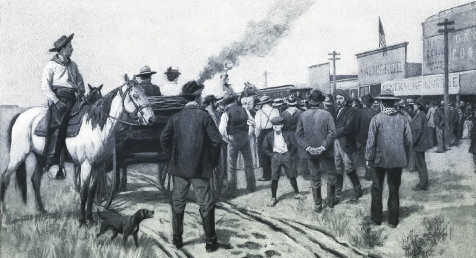

The village in which Grayson was speaking was a tiny place of twelve or fifteen houses, all square, unadorned, and ugly, standing in the centre of an illimitable prairie that rolled away on either side exactly like the waves of the sea, and with the same monotony. It was a weather-beaten gathering. The prairie winds are not good for the complexion, and the cheeks of these people were brown, not red. On the outskirts of the crowd, still sitting on their ponies, were cowboys, who had ridden sixty miles across the Wyoming border to hear Grayson speak. They were dressed exactly like the cowboys of the pictures that Harley had seen in magazine stories of the Western plains. They wore the sombreros and leggings and leather belts, but there was no disorder, no cursing, no shouting nor yelling. This was a phase that had passed.

They listened, too, with an eagerness that few Eastern audiences could show. This was not to them an entertainment or anything savoring of the spectacular; it was the next thing to the word of God. There was a reverence in their manner and bearing that appealed to Harley, and he read easily in their minds the belief that Jimmy Grayson was the greatest man in the world, and that he alone could bring to their country the greatness that they wished as much for the country as for themselves. Churchill sneered at this tone of the gathering, but Harley took another view. These men might be ignorant of the world, but he respected their hero-worship, and thought it a good quality in them.

They heard the candidate tell of mighty corporations, of a vague and distant place called Wall Street, where fat men, with soft, white fingers and pouches under their eyes, sat in red-carpeted offices and pulled little but very strong strings that made farmers on the Western plains, two thousand miles away, dance like jumping-jacks, just as the fat men wished, and just when they wished. These fat men were allied with others in Europe, pouchy-eyed and smooth-fingered like themselves, and it was their object to own all the money-bags of the world, and gather all the profits of the world’s labor. Harley, watching these people, saw a spark appear in their eyes many times, but it was always brightest at the mention of Wall Street. That both speaker and those to whom his words were spoken were thoroughly sincere, he did not doubt for a moment.

Grayson ceased, the engine blew the starting signal, the candidate and the correspondent swung aboard, and off they went. Harley looked back, and as long as he could see the station the little crowd on the lone prairie was still watching the disappearing train. There was something pathetic in the sight of these people following with their eyes until the last moment the man whom they considered their particular champion.

It was but an ordinary train of day cars, the red plush of the seats now whitened by the prairie dust, and it was used in common by the candidate, the flock of correspondents, and a dozen politicians, the last chiefly committeemen or their friends, one being the governor of the state through which they were then travelling.

Harley sought sleep as early as possible that night, because he would need all his strength for the next day, which was to be a record-breaker. A tremendous programme had been mapped out for Jimmy Grayson, and Harley, although aware of the candidate’s great endurance, wondered how he would ever stand it. They were to cut the state from southeast to northwest, a distance of more than four hundred miles, and twenty-four speeches were to be made by the way. Fresh from war, Harley did not remember any more arduous journey, and, like an old campaigner, he prepared for it as best he could.

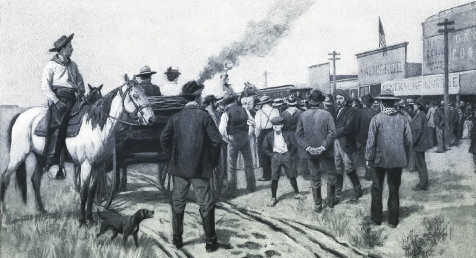

It was not yet daylight when they were awakened for the start of the great day. A cold wind moaned around the hamlet as they ate their breakfast, and then hastened, valise in hand, and still half asleep, to the train, which stood steam up and ready to be off. They found several men already on board, and Churchill, when he saw them, uttered the brief word, “Natives!” They were typical men of the plains, thin, dry, and weather-beaten, and the correspondents at first paid but little attention to them. It was common enough for some local committeeman to take along a number of friends for a half-day or so, in order that they might have a chance to gratify their curiosity and show their admiration for the candidate.

But the attention of Harley was attracted presently by one of the strangers, a smallish man of middle age, with a weak jaw and a look curiously compounded of eagerness and depression.

The stranger’s eye met Harley’s, and, encouraged by his friendly look, he crossed the aisle and spoke to the correspondent.

“You are one of them newspaper fellers that travels with Grayson, ain’t you?” he asked.

Harley admitted the charge.

“And you see him every day?” continued the little man, admiringly.

“Many times a day.”

“My! My! Jest to think of your comin’ away out here to take down what our Jimmy Grayson says, so them fellers in New York can read it! I’ll bet he makes Wall Street shake. I wish I was like you, mister, and could be right alongside Jimmy Grayson every day for weeks and weeks, and could hear every word he said while he was poundin’ them fellers in Wall Street who are ruinin’ our country. He is the greatest man in the world. Do you reckon I could get to speak to him and jest tech his hand?”

“Why, certainly,” replied Harley. He was moved by the little man’s childlike and absolute faith and his reverence for Jimmy Grayson as a demigod. It was not without pathos, and Harley at once took him into the next car and introduced him to Grayson, who received him with the natural cordiality that never deserted him. Plover, the little man said was his name—William Plover, of Kalapoosa, Choctaw County. He regarded Grayson with awe, and, after the hand-shake, did not speak. Indeed, he seemed to wish no more, and made himself still smaller in a corner, where he listened attentively to everything that Grayson said.

He also stood in the front row at each stopping-place, his eyes fixed on Grayson’s face while the latter made his speech. The candidate, by-and-by, began to notice him there. It is often a habit with those who have to speak much in public to fix the eye on some especially interested auditor and talk to him directly. It assists in a sort of concentration, and gives the orator a willing target.

Grayson now spoke straight to Plover, and Harley watched how the little man’s emotions, as shown in his face, reflected in every part the orator’s address. There was actual fire in his eyes, whenever Grayson mentioned that ogre, Wall Street, and tears rose when the speaker depicted the bad condition of the Western farmer.

“Wouldn’t I like to go on to Washington with Jimmy Grayson when he takes charge of the government!” exclaimed Plover to Harley when this speech was finished—“not to take a hand myself, but jest to see him make things hum! Won’t he make them fat fellers in Wall Street squeal! He’ll have the Robber Barons squirmin’ on the griddle pretty quick, an’ wheat’ll go straight to a dollar a bushel, sure! I can see it now!”

His exultation and delight lasted all the morning; but in the afternoon the depressed, crushed feeling which Harley had noticed at first in his look seemed to get control.

Although his interest in Grayson’s speeches and his devout admiration did not decrease, Plover’s melancholy grew, and Harley by-and-by learned the cause of it from another man, somewhat similar in aspect, but larger of figure and stronger of face.

“To tell you the truth, mister,” said the man, with the easy freedom of the West, “Billy Plover—and my cousin he is, twice removed—my name’s Sandidge—is runnin’ away.”

“Running away?” exclaimed Harley, in surprise. “Where’s he running to, and what’s he running from?”

“Where he’s runnin’ to, I don’t know—California, or Washington, or Oregon, I guess. But I know mighty well what he’s runnin’ away from; it’s his wife.”

“Ah, a family trouble?” said Harley, whose delicacy would have caused him to refrain from asking more. But the garrulous cousin rambled on.

“It’s a trouble, and it ain’t a trouble,” he continued. “It’s the weather and the crops, or maybe because Billy ain’t had no weather nor no crops, either. You see, he’s lived for the last ten years on a quarter-section out near Kalapoosa, with his wife, Susan, a good woman and a terrible hard worker, but the rain’s been mighty light for three seasons, and Billy’s wheat has failed every time. It’s kinder got on his temper, and, as they ain’t got any children to take care of, Billy he’s been takin’ to politics. Got an idea that he can speak, though he can’t, worth shucks, and thinks he’s got a mission to whack Wall Street, though I ain’t sure but what Wall Street don’t deserve it. Susan says he ain’t got any business in politics, that he ought to leave that to better men, an’ stay an’ wrastle with the ground and the weather. So that made them take to spattin’.”

“And the upshot?”

“Waal, the upshot was that Billy said he could stand it no longer. So last night he raked up half the spare cash, leavin’ the rest and the farm and stock to Susan, an’ he loped out. But first he said he had to hear Jimmy Grayson, who is mighty nigh a whole team of prophets to him, and, as Jimmy’s goin’ west, right on his way, he’s come along. But to-night, at Jimmy’s last stoppin’-place, he leaves us and takes a train straight to the coast. I’m sorry, because if Susan had time to see him and talk it over—you see, she’s the man of the two—the whole thing would blow over, and they’d be back on the farm, workin’ hard, and with good times ahead.”

Harley was moved by this pathetic little tragedy of the plains, the result of loneliness and hard times preying upon the tempers of two people. “Poor devil!” he thought. “It’s as his cousin says; if Susan could only be face to face with him for five minutes, he’d drop his foolish idea of running away and go home.”

Then of that thought was born unto him a great idea, and he immediately hunted up the cousin again.

“Is Kalapoosa a station on the telegraph line?” he asked.

“Oh yes.”

“Would a telegram to that point be delivered to the Plover farm?”

“Yes. Why, what’s up?”

“Nothing; I just wanted to know. Now,can you tell me what time to-night, after our arrival, a man may take a train for the coast from Weeping Water, our last stop?”

“We’re due at Weepin’ Water,” replied the cousin, “at eleven to-night, but I cal’late it’ll be nigher twelve when we strike the town. You see, this is a special train, runnin’ on any old time, an’ it’s liable now and then to get laid out a half an hour or more. But, anyhow, we ought to beat the Denver Express, which is due at twelve-thirty in the mornin’, an’ stops ten minutes at the water-tank. It connects at Denver with the ’Frisco Express, an’ I guess it’s the train that Billy will take.”

“Does the Denver Express stop at Kalapoosa?”

“Yes. Kalapoosa ain’t nothin’ but a little bit of a place, but the Pawnee branch line comes in there, and the express gets some passengers off it. Say, mister, what’s up?”

But Harley evaded a direct answer, having now all the information he wished. He went back to the next car and wrote this despatch:

KALAPOOSA.

SUSAN PLOVER,—Take to-day’s Denver Express and get off to-night at Weeping Water. You will find me at Grayson’s speaking, standing just in front of him. Don’t fail to come. Will explain everything to you then.

William Plover.

Harley looked at this message with satisfaction. “I guess I’m a forger,” he mused; “but as the essence of wrong lies in the intention, I’m doing no harm.”

He stopped at the next station, prepaid the message, and, standing by, saw with his own eyes the operator send it. Then he returned to the train and resumed his work with fresh zest.

And he had plenty to do. He had seen Jimmy Grayson make great displays of energy, but his vitality on this terrible day was amazing. On and on they went, right into the red eye of the sun. The hot rays poured down, and the dust whirled over the plain, entering the car in clouds, where it clothed everything—floors, seats, and men alike—until they were a uniform whitey-brown. It crept, too, into Harley’s throat and stung his eyelids, but at each new speech the candidate seemed to rise fresher and stronger than ever, and at every good point he made the volleys of applause rose like rifle-shots.

Harley, at the close of a speech late in the day, sought his new friend, Plover. The little man was crushed down in a seat, looking very gloomy. Harley knew that he was thinking of Kalapoosa, the spell of Grayson’s eloquence being gone for the moment.

“Tired, Mr. Plover?” said Harley, putting a friendly hand on his shoulder.

“A little bit,” replied Plover.

“But it’s a great day,” continued Harley. “I tell you, old man, it’s one to be remembered. There never was such a campaign. The story of this ride will be in all the papers of the United States to-morrow.”

“Ain’t he great! Ain’t he great!” exclaimed Plover, brightening into enthusiasm. “And don’t he hit Wall Street some awful whacks?”

“He certainly is great,” replied Harley. “But you wait until we get to Weeping Water. That’s the last stop, and he’ll just turn himself loose there. You mustn’t miss a word.”

“I won’t,” replied Plover. “I’ll have time, because the Denver Express, on which I’m going to ’Frisco, don’t leave there till twelve-forty. No, I won’t miss the big speech at Weeping Water.”

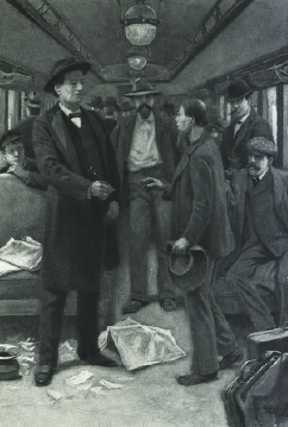

They reached Weeping Water at last, although it was full midnight, and they were far behind time, and together they walked to the speaker’s stand.

Harley saw Plover in his accustomed place in the front rank, just under the light of the torches, where he would meet the speaker’s eye, his face rapt and worshipful. Then he looked at his watch.

“Twelve-fifteen,” he said to himself. “The Denver Express will be here in another fifteen minutes, and Susan will fall on the neck of her Billy.”

Then he stopped to listen to Grayson. Never had Harley seen him more earnest, more forcible. He knew that the candidate must be sinking from physical weakness—his pale, drawn face showed that—but his spirit flamed up for this last speech, and the crowd was wholly under the spell of his powerful appeal.

Harley met, presently, the cousin, Sandidge.

“This is Grayson’s greatest speech of the day,” Harley said, “and how it must please Mr. Plover!”

“That’s so,” replied Sandidge; “but Billy’s all broke up over it.”

“Why, what’s the matter?” asked Harley, in sudden alarm.

“The Denver Express is nearly two hours and a half late—won’t be here until three, and at Denver it’ll miss the ’Frisco Express; won’t be another for a day. So Billy, who’s in a hurry to get to the coast—the old Nick’s got into him, I reckon—is goin’ by the express on the B. P.; the train on the branch line that goes out there at two-ten connects with it, and so does the accommodation freight at two-forty. It’s hard on Billy—he hates to miss any of Jimmy Grayson’s speeches, but he’s bound to go.”

Harley was touched by real sorrow. He drew his pencil-pad from his pocket, hastily wrote a few lines upon it, pushed his way to the stage, and thrust what he had written into Mr. Grayson’s hands. The speaker, stopping to take a drink of water, read this note:

Dear Mr. Grayson,—The Denver Express is two hours and a half late. For God’s sake speak until it comes; you will hear it at three, when it pulls into the station.

It is a matter of life and death, and while you are speaking don’t take your eye off the little man with the whiskers, who has been with us all day, and who always stands in front and looks up at you.

I’ll explain everything later, but please do it. Again I say it’s a matter of life and death.

John Harley.

Grayson looked in surprise at Harley, but he caught the appealing look on the face of the correspondent. He liked Harley, and he knew that he could trust him. He knew, moreover, that what Harley had written in the note must be true.

Grayson did not hesitate, and, nodding slightly to Harley, turned and faced the crowd, like a soldier prepared for his last and desperate charge. His eyes sought those of the little man, his target, looking up at him. Then he fixed Plover with his gaze and began.

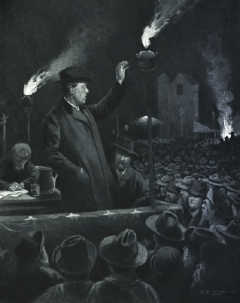

They still tell in the West of Jimmy Grayson’s speech at Weeping Water, as the veterans tell of Pickett’s rush in the flame and the smoke up Cemetery Hill. He had gone on the stage a half-dead man. He had already been speaking nineteen hours that day. His eyes were red and swollen with train dust, prairie dust, and lack of sleep. Every bone in him ached. Every word stung his throat as it came, and his tongue was like a hot ember in his mouth. Deep lines ran away from his eyes.

But Jimmy Grayson was inspired that night on the black prairie. The words leaped in livid flame from his lips. Never was his speech more free and bold, and always his burning eyes looked into those of Plover and held him.

Closer and closer pressed the crowd. The darkness still rolled up, thicker and blacker than ever. Grayson’s shoulders sank away, and only his face was visible now. The wind rose again, and whistled around the little town and shrieked far out on the lonely prairie. But above it rose the voice of Grayson, mellow, inspiring, and flowing full and free.

Harley looked and listened, and his admiration grew and grew. “I don’t agree with all he says,” he thought, “but, my God! how well he says it.”

Then he cowered in the lee of a little building, that he might shelter himself from the bitter wind that was searching him to the marrow.

Time passed. The speaker never faltered. A half-hour, an hour, and his voice was still full and mellow, nor had a soul left the crowd. Grayson himself seemed to feel a new access of strength from some hidden source, and his form expanded as he denounced the Trusts and the Robber Barons, and all the other iniquities that he felt it his duty to impale, but he never took his eyes from Plover; to him he was now talking with a force and directness that he had not equalled before. Time went on, and, as if half remembering some resolution, Plover’s hand stole towards the little old silver watch that he carried in the left-hand pocket of his waistcoat. But just at that critical moment Grayson uttered the magical name, Wall Street, and Plover’s hand fell back to his side with a jerk. Then Grayson rose to his best, and tore Wall Street to tatters.

A whistle sounded, a bell rang, and a train began to rumble, but no one took note of it save Harley. The two-ten on the branch line to connect with the ’Frisco Express on the B. P. was moving out, and he breathed a great sigh of relief. “One gone,” he said to himself; “now for the accommodation freight.”

The speech continued, but presently Grayson stopped for a hasty drink of water. Harley trembled. He was afraid that Grayson was breaking down, and his fears increased when he saw Plover’s eyes leave the speaker’s face and wander towards the station. But just at that moment the candidate caught the little man.

“Listen to me!” thundered Grayson, “and let no true citizen here fail to heed what I am about to tell him.”

Plover could not resist the voice and those words of command. His thoughts, wandering towards the railroad station, were seized and brought back by the speaker. His eyes were fixed and held by Grayson, and he stood there as if chained to the spot.

Time became strangely slow. The accommodation freight must be more than ten minutes late, Harley thought. He looked at his watch, and found that it was not due to leave for five minutes yet. So he settled himself to patient waiting, and listened to Grayson as he passed from one national topic to another. He saw, too, that the lines in the speaker’s face were growing deeper and deeper, and he knew that he must be using his last ounces of strength. His soul was stirred with pity. Yet Grayson never faltered.

The whistle blew, the bell rang, and again the train rumbled. The two-forty accommodation freight on the branch line to connect with the ’Frisco Express on the B. P. was moving out, and Plover had been held. He could not go now, and once more Harley breathed that deep sigh of relief. Twenty minutes passed, and he heard far off in the east a faint rumble. He knew it was the Denver Express, and, in spite of his resolution, he began to grow nervous. Suppose the woman should not come?

The rumble grew to a roar, and the train pulled into the station. Grayson was faithful to the last, and still thundered forth the invective that delighted the soul of Plover. The train whistled and moved off again, and Harley waited in breathless anxiety.

A tall form rose out of the darkness, and a woman, middle-aged and honest of face, appeared. The correspondent knew that it must be Susan. It could be nobody else. She was looking around as if she sought some one. Harley’s eye caught Grayson’s, and it gave the signal.

“And now, gentlemen,” said the candidate, “I am done. I thank you for your attention, and I hope you will think well of what I have said.”

So saying, he left the stage, and the crowd dispersed. But Harley waited, and he saw Plover and his wife meet. He saw, too, the look of surprise and then joy on the man’s face, and he saw them throw their arms around each other’s neck and kiss in the dark. They were only a poor, prosaic, and middle-aged couple, but he knew they were now happy and that all was right between them.

When Grayson went to his room, he fell from exhaustion in a half-faint across the bed; but when Harley told him the next afternoon the cause of it all, he laughed and said it was well worth the price.

They obtained, about a week later, the New York papers containing an account of the record-breaking day. When Harley opened the Monitor, Churchill’s paper, he read these headlines:

But when he looked at the Gazette, he saw the following head-lines over his own account:

Harley sighed with satisfaction. “That managing editor of mine knows his business,” he said to himself.