5 On the Great River

They remained just within the edge of the forest, but, despite the lack of moonlight, they could see far over the surface of the river. It seemed to be an absolutely clean sweep of waters, as free from boats as if man had never come, but, after long looking, Henry thought that he could detect a half dozen specks moving southward. It was only for a moment, and then the specks were gone.

“I’m sure it was the Spanish boats,” said Henry, “and I think they’ve given up the hunt.”

“More’n likely,” said Sol, “an’ I guess it’s about time fur us to pull across an’ pick up Paul an’ Tom an’ Jim. They’ll wonder what hez become o’ us. An’ say, Henry, won’t they be s’prised to see us come proudly sailin’ into port in our gran’ big gall-yun, all loaded down with arms an’ supplies an’ treasures that we hev captured?”

Sol spoke in a tone of deep content, and Henry replied in the same tone:

“If they don’t they’ve changed mightily since we left ’em.”

Both, in truth, were pervaded with satisfaction. They felt that they had never done a better night’s work. They had a splendid boat filled with the most useful supplies. As Sol truthfully said, it was one thing to walk a thousand miles through the woods to New Orleans and another to float down on the current in a comfortable boat. They had cause for their deep satisfaction.

They pulled with strong, steady strokes across the Mississippi, taking a diagonal course, and they stopped now and then to look for a possible enemy. But they saw nothing, and at last their boat touched the western shore. Here Sol uttered their favorite signal, the cry of the wolf, and it was quickly answered from the brush.

“They’re all right,” said Henry, and presently they heard the light footsteps of the three coming fast.

“Here, Paul, here we are!” called out Sol a few moments later, “an’ min’, Paul, that your moccasins are clean. We don’t allow no dirty footsteps on this magnificent, silver-plated gall-yun o’ ours, an’ ez fur Jim Hart, ef the Mississippi wuzn’t so muddy I’d make him take a bath afore he come aboard.”

Henry and the shiftless one certainly enjoyed the surprise of their comrades who stood staring.

“I suppose you cut her out, took her from the Spaniards?” said Paul.

“We shorely did,” replied Sol, “an’, Paul, she’s a shore enough gall-yun, one o’ the kind you told us them Spaniards had, ’cause she’s full o’ good things. Jest come on board an’ look.”

The three were quickly on the boat and they followed Sol with surprise and delight, as he showed them their new treasures one by one.

“You’ve named her right, Sol,” said Paul. “She is a galleon to us, sure enough, and that’s what we’ll call her, ‘The Galleon.’ When we have time, Sol, you and I will cut that name on her with our knives.”

They tied their boat to a sapling and kept the oars and themselves aboard. Tom Ross volunteered to keep the watch for the few hours that were left of the night. The others disposed themselves comfortably in the boat, wrapped their bodies in the beautiful new Spanish blankets, and were soon sound asleep.

Tom sat in the prow of the boat, his rifle across his knees, and his keen hunting knife by his side. At the first sign of danger from shore he could cut the rope with a single slash of his knife and push the boat far out into the current.

But there was no indication of danger nor did the indefinable sixth sense, that came of long habit and training, warn him of any. Instead, it remained a peaceful night, though dark, and Tom looked contemplatively at his comrades. He was the oldest of the little party and a man of few words, but he was deeply attached to his four faithful comrades. Silently he gave thanks that his lot was cast with those whom he liked so well.

The night passed away and up came a beautiful dawn of rose and gold. Tom Ross awakened his comrades.

“The day is here,” he said, “an’ we must be up an’ doin’ ef we’re goin’ to keep on the trail o’ them Spanish fellers.”

“All right,” said Shif’less Sol, opening his eyes. “Jim Hart, is my breakfus ready? Ef so, you kin jest bring it to me while I’m layin’ here an’ I’ll eat it in bed.”

“Your breakfus ready!” replied Jim Hart indignantly. “What sort uv nonsense are you talkin’ now, Sol Hyde?”

“Why, ain’t you the ship’s cook?” said Sol in a hurt tone, “an’ oughtn’t you to be proud o’ bein’ head cook on a splendiferous new gall-yun like this? I’d a-thought, Jim, you’d be so full o’ enthusiasm over bein’ promoted that you’d have had ready fur us the grandest breakfus that wuz ever cooked by a mortal man fur mortal men. It wuz sech a fine chance fur you.”

“I think we can risk a fire,” said Henry. “The Spaniards are far out of sight, and warm food will be good for us.”

After they had eaten, Henry poured a few drops of the Spanish liquor for each in a small silver cup that he found in one of the lockers.

“That will hearten us up,” he said, but directly after they drank it Paul, who had been making an exploration of his own on the boat, uttered a cry of joy.

“Coffee!” he said, as he dragged a bag from under a seat, “and here is a pot to boil it in.”

“More treasures,” said Sol gleefully. “That wuz shorely a good night’s work you an’ me done, Henry!”

There was nothing to do but boil a pot of the coffee then and there, and each had a long, delicious drink. Coffee and tea were so rare in the wilderness that they were valued like precious treasures. Then they packed their things and started, pulling out into the middle of the stream and giving the current only a little assistance with the oars.

“One thing is shore,” said Shif’less Sol, lolling luxuriously on a locker, “that Spanish gang can’t git away from us. All we’ve got to do is to float along ez easy ez you please, an’ we’ll find ’em right in the middle o’ the road.”

“It does beat walkin’,” said Jim Hart, with equal content, “but this is shorely a pow’ful big river. I never seed so much muddy water afore in my life.”

“It’s a good river, a kind river,” said Paul, “because it’s taking us right to its bosom, and carrying us on where we want to go with but little trouble to us.”

It was to Paul, the most imaginative of them all, to whom the mighty river made the greatest appeal. It seemed beneficent and kindly to him, a friend in need. Nature, Paul thought, had often come to their assistance, watching over them, as it were, and helping them when they were weakest. And, in truth, what they saw that morning was enough to inspire a bold young wilderness rover.

The river turned from yellow to a lighter tint in the brilliant sunlight. Little waves raised by the wind ran across the slowly-flowing current. As far as they could see the stream extended to eastward, carried by the flood deep into the forest. The air was crisp, with the sparkle of spring, and all the adventurers rejoiced.

Now and then great flocks of wild fowl, ducks and geese, flew over the river, and they were so little used to man that more than once they passed close to the boat.

“The Spaniards are too far away to hear,” said Henry, “and the next time any wild ducks come near I’m going to try one of these fowling pieces. We need fresh ducks, anyway.”

He took out a fowling piece, loaded it carefully with the powder and shot that the locker furnished in abundance and waited his time. By and by a flock of wild ducks flew near and Henry fired into the midst of them. Three lay floating on the water after the shot, and when they took them in Long Jim Hart, a master on all such subjects, pronounced them to be of a highly edible variety.

Paul, meanwhile, took out one of the small swords and examined it critically.

“It is certainly a fine one,” he said, “I suppose it’s what they call a Toledo blade in Spain, the finest that they make.”

“Could you do much with it, Paul?” asked Shif’less Sol.

“I could,” replied Paul confidently. “Mr. Pennypacker served in the great French war. He was at the taking of Quebec, and he learned the use of the sword from good masters. He’s taught me all the tricks.”

“Maybe, then,” said Sol laughing, “you’ll have to fight Alvarez with one o’ them stickers. Ef sech a combat is on it’ll fall to you, Paul. The rest of us are handier with rifle an’ knife.”

“It’s never likely to happen,” said Paul.

The morning passed peacefully on, and the glory of the heavens was undimmed. The river was a vast, murmuring stream, and the five voyagers felt that, for the present, their task was an easy one. A single man at the oars was sufficient to keep the boat moving as fast as they wished, and the rest occupied themselves with details that might provide for a future need.

Paul brought out one of the beautiful small swords again, and fenced vigorously with an imaginary antagonist. Jim Hart took a captured needle and thread and began to mend a rent in his attire. Henry lifted the folded tent from the locker and looked carefully at the cloth.

“I think that with this and a pole or two we might fix up a sail if we needed it,” he said. “We don’t know anything about sails, but we can learn by trying.”

Tom Ross was at the oars, but Shif’less Sol lay back on a locker, closed his eyes, and said:

“Jest wake me up, when we git to New Or-lee-yuns. I could lay here an’ sleep forever, the boat rockin’ me to sleep like a cradle.”

They saw nothing of the Spanish force, but they knew that such a flotilla could not evade them. Having no reason to hide, the Spaniards would not seek to conceal so many boats in the flooded forest. Hence the five felt perfectly easy on that point. About noon they ran their own boat among the trees until they reached dry land. Here they lighted a fire and cooked their ducks, which they found delicious, and then resumed their leisurely journey.

The afternoon was as peaceful as the morning, but it seemed to the sensitive imagination of Paul that the wilderness aspect of everything was deepening. The great flooded river broadened until the line of water and horizon met, and Paul could easily fancy that they were floating on a boundless sea. An uncommonly red sun was setting and here and there the bubbles were touched with fire. Far in the west dark shadows were stealing up.

“Look,” Henry suddenly exclaimed, “I think that the Spanish have gone into camp for the night!”

He pointed down the stream and toward the western shore, where a thin spire of smoke was rising.

“It’s that, certain,” said Tom Ross, “an’ I guess we’d better make fur camp, too.”

They pulled toward the eastern shore, in order that the river might be between them and the Spaniards during the night and soon reached a grove which stood many feet deep in the water. As they passed under the shelter of the boughs they took another long look toward the spire of smoke. Henry, who had the keenest eyes of all, was able to make out the dim outline of boats tied to the bank, and any lingering doubt that the Spaniards might not be there was dispelled.

“When they start in the morning we’ll start, too,” said Henry.

Then they pushed their boat further back into the grove. Night was coming fast. The sun sank in the bosom of the river, the water turned from yellow to red and then to black, and the earth lay in darkness.

“I think we’d better tie up here and eat cold food,” said Henry.

“An’ then sleep,” said Shif’less Sol. “That wuz a mighty comf’table Spanish blanket I had last night an’, Jim Hart, I want to tell you that if you move ’roun’ to-night, while you’re watchin’, please step awful easy, an’ be keerful not to wake me ’cause I’m a light sleeper. I don’t like to be waked up either early or late in the night. Tain’t good fur the health. Makes a feller grow old afore his time.”

“Sol,” said Henry, who was captain by fitness and universal consent, “you’ll take the watch until about one o’clock in the morning and then Paul will relieve you.”

Jim Hart doubled up his long form with silent laughter, and smote his knee violently with the palm of his right hand.

“Oh, yes, Sol Hyde,” he said, “I’ll step lightly, that is, ef I happen to be walkin’ ’roun’ in my sleep, an’ I’ll take care not to wake you too suddenly, Sol Hyde. I wouldn’t do it for anything. I don’t want to stunt your growth, an’ you already sech a feeble, delicate sort o’ creetur, not able to take nourishment ’ceptin’ from a spoon.”

“Thar ain’t no reward in this world fur a good man,” said the shiftless one in a resigned tone.

They ate quickly, and, as usual, those who did not have to watch wrapped themselves in their blankets and with equal quickness fell asleep. Shif’less Sol took his place in the prow of the boat, and his attitude was much like that of Tom Ross the night before, only lazier and more graceful. Sol was a fine figure of a young man, drooped in a luxurious and reclining attitude, his shoulder against the side of the boat, and a roll of two blankets against his back. His eyes were half closed, and a stray observer, had there been any, might have thought that he was either asleep or dreaming.

But the shiftless one, fit son of the wilderness, was never more awake in his life. The eyes, looking from under the lowered lids, pierced the forest like those of a cat. He saw and noted every tree trunk within the range of human vision, and no piece of floating debris on the surface of the flooded river escaped his attention. His sharp ears heard, too, every sound in the grove, the rustle of a stray breeze through the new leaves, or the splash of a fish, as it leaped from the water and sank back again.

The hours dragged after one another, one by one, but Shif’less Sol was not unhappy. He was really quite willing to keep the watch, and, as Tom Ross had done, he regarded his sleeping comrades with pride, and all the warmth of good fellowship.

The night was dark, like its predecessor. The moon’s rays fell only in uneven streaks, and revealed a singular scene, a forest standing knee deep, as it were, in water.

Shif’less Sol presently took one of the blankets and wrapped it around his shoulders. A cold damp pervaded the atmosphere, and a fog began to rise from the river. The shiftless one was a cautious man and he knew the danger of chills and fever. His comrades were already well wrapped, but he stepped softly over and drew Paul’s blanket a little closer around his neck. Then he resumed his seat, maintaining his silence.

Shif’less Sol did not like the rising of the river fog. It was thick and cold, it might be unhealthy, and it hid the view. His circle of vision steadily narrowed. Tree trunks became ghostly, and then were gone. The water, seen through the fog, had a pallid, unpleasant color. Eye became of little use, and it was ear upon which the sentinel must depend.

Shif’less Sol judged that it was about midnight, and he became troubled. The sixth sense, that comes of acute natural perceptions fortified by long habit, was giving him warning. It seemed to him that he felt the approach of something. He raised himself up a little higher and stared anxiously into the thick mass of white fog. He could make out nothing but a little patch of water and a few ghostly tree trunks near by. Even the stern of the boat was half hidden by the fog.

“Wa’al,” thought the shiftless one philosophically, “ef it’s hard fur me to find anything it’ll be hard fur anything to find us.”

But his troubled mind would not be quiet. Philosophy was not a sufficient reply to the warning of the sixth sense, and, leaning far over the edge of the boat, he listened with ears long trained to every sound of the wilderness. He heard only the stray murmur of the wind among the leaves—and was that a ripple in the water? He strained his ears and decided that it was either a ripple or the splash of a fish, and he sank back again in his seat.

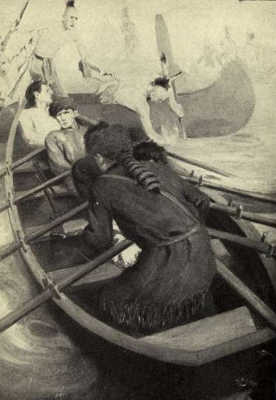

Although he had resumed his old position, the shiftless one was not satisfied. The feeling of apprehension, like a mysterious mental signal, was not effaced. That thick, whitish fog was surcharged with an alien quality, and slowly he raised himself up once more. Hark! was it the ripple again? He rose half to his feet, and instantly his eye caught a glimpse of something brown upon the edge of the boat. It was a human hand, the brown, powerful hand of a savage.

The glance of Shif’less Sol followed the hand and saw a brown face emerging from the water and fog. Quick as a flash he fired. There was a terrible, unearthly cry, the hand slipped from the boat and the head sank from view.

“Up! up! boys!” cried Sol in thunderous tones. “We’re attacked by swimmin’ savages!”

He snatched up one of the double-barreled pistols and fired at another head on the water. The others were awake in an instant and rose up, rifles in hand. But they saw only a splash of blood on the stream that was gone in a moment, then the thick, whitish fog closed in again, and after that silence! But they knew Sol too well to doubt him, and the momentary red splash would have converted even the ignorant.

“Lie low!” exclaimed Henry. “Everybody down behind the sides of the boat! They may fire at any time!”

The boat was built of thick timber, through which no bullet of that time could go, and they crouched down, merely peeping over the edges and presenting scarcely any target. They had their own rifles and the extra fowling pieces and pistols were made ready, also.

But nothing came from the great pall of whitish fog, and the silence was chilly and heavy. It was the most uncanny thing in all Paul’s experience. Beyond a doubt they were surrounded by savage enemies, but from which side they would come, and when, nobody could tell until they were at the very side of the boat.

“How many did you see, Sol?” whispered Henry.

“Only two, but one of ’em won’t ever attack us again.”

“The others must be near by in their canoes, and the swimmers may have been scouts and skirmishers. They know where we are, but we don’t know where they are.”

“That’s so,” said Shif’less Sol, “an’ it gives ’em an advantage.”

“Which, perhaps, we can take from ’em by moving our own boat.”

Henry was about to put his plan into action, but they heard a light splash in the water to the west, and another to the north. Spots of piercing red light appeared in the fog, and many rifles cracked. Fortunately, all had thrown themselves down, and the bullets spent themselves in the wood of the boat’s side. Henry and Sol and Tom fired back at the flashes, but more rifle shots came out of the fog, and those on the boat had no way of telling whether any of their bullets had hit.

“I think we’d better hold our fire,” whispered Henry between rifle shots. “It’s wasting bullets to shoot at a fog.”

The others nodded and waited. A long cry, quavering at first, and then rising to a fierce top note to die away later in a ferocious, wolfish whine came through the fog. It was uttered by many throats, and in the uncanny, whitish gloom it seemed to be on all sides of them. Then shouts and shots both ceased and the heavy silence came again.

“Now is our time,” whispered Henry. “Paul, steer southward. Jim, you and Tom row, and Sol and I will be ready with the guns. Keep your heads down as low as you can.”

Jim Hart and Tom Ross took the oars, pulling them through the water with extreme caution and slowness. All knew that sharp ears were listening in the flooded forest, and the splash of oars would bring the war canoes at once. But they were determined that the fog which was such a help to their enemies should be an equal help to them also.

Slowly the heavy boat crept through the water. Paul, at the tiller, steered with judgment and craft, and his was no light task. Now and then low boughs were lapped in the water and bushes submerged to their tops grew in the way. To become tangled in them might be fatal and to scrape against them would be a signal to their enemies, but Paul steered clear every time.

They had gone perhaps fifty yards when Henry gave a signal to stop and Jim and Tom rested on their oars. Then they heard a burst of firing behind them, and a smile of saturnine triumph spread slowly but completely over the face of Shif’less Sol.

“They’re shootin’ at the place whar we wuz, an’ whar we ain’t now,” he whispered to Henry.

“Yes,” Henry whispered back, “they haven’t found out yet that we’ve left, but they are likely to do it pretty soon. I hope now that this fog will hang on just as thick as it can. Start up again, boys.”

“’Twould be funny,” whispered Sol, “ef the savages should find us an’ chase us right into the bosoms o’ the Spaniards.”

“Yes,” replied Henry, “and for that reason I think we’d better bend around a circle and then go up stream. I’ll tell Paul to steer that way.”

They went on again, creeping through the white darkness; fifty yards or so at a time, and then a pause to listen. Henry judged that they were about a half mile from their original anchorage, when the solemn note of an owl arose, to be answered by a similar note from another point.

“They’ve discovered our departure,” he whispered, “and they’re telling it to each other. I imagine that their war canoes will now come in a kind of half circle toward the center of the river. They’ll guess that we won’t retreat toward the land, because then we might be hemmed in.”

“No doubt of it,” replied Sol, “and I think we’d better pull off toward the north now. Mebbe we kin give ’em the slip.”

Henry gave the word and Paul steered the boat in the chosen course. The forest grew thinner, showing that they were approaching the true stream, but the fog held fast. After a hundred yards or so they stopped again, and then they distinctly heard the sound of paddles to their right. It was not a great splash, but they knew it well. Paul, at the tiller, fancied that he could see the faces of the savages bending over their paddles. They were eager, he knew, for their prey, and either chance or instinct had brought them through the white pall in the right course.

The uncertainty, the fog, and the great mysterious river weighed upon Paul. He wished, for a moment, that the vapors might lift, and then they could fight their enemies face to face. He glanced at his own comrades and they had taken on an unearthly look. Their forms became gigantic and unreal in the white darkness. As Henry leaned forward to listen better his figure was distorted like that of a misshapen giant.

“Steer straight toward the north, Paul,” he whispered. “We must shake them off somehow or other.”

Silently the boat slid through the water but they heard again those signal cries, the hoots of the owl and now they were much nearer.

“They must have guessed our course,” whispered Henry, “or perhaps they have heard the splash of an oar now and then. Stop, boys, and let’s see if we can hear their canoes.”

Their boat lay under the thick, spreading boughs of some oaks. Paul could see the branches and twigs showing overhead through the white fog like lace work, but everything else was invisible twenty feet away. All heard, however, now and then the faint splash, splash of paddles, perhaps a hundred yards distant. Henry tried to tell from the sounds how many war canoes might be in the party, and he hazarded a wild guess of twenty. As he listened, the splash grew a little louder. Obviously the canoes were keeping on the right course. Shif’less Sol wet his finger and held it up. When he took it down he whispered in some alarm to Henry:

“The wind has begun to blow, an’ it’s shore to rise. It’ll blow the fog away, an’ we’ll lay in plain sight o’ all o’ them savages.”

Henry’s instinct for generalship rose at once and he saw a plan.

“We must keep on for midstream,” he said. “We know what direction that is, and, out in open water, we’d have one advantage even over their numbers. Theirs are only light canoes, while ours is a big strong boat that will shelter us from any bullet. Pull away, boys! I’ll help Sol keep up the watch.”

The boat once more resumed its progress toward the main current. The wind, as Sol had predicted, rapidly grew stronger. The deep curtain of fog began to thin and lighten. Suddenly a canoe appeared through it and then a second.

A bullet, fired from the first canoe, whizzed dangerously near the head of Shif’less Sol. He replied instantly, but the light was so uncertain and tricky that he missed the savage at whom he had aimed. The heavy bullet instead ploughed through the side and bottom of the bark canoe, which rapidly filled and sank, leaving its occupants struggling in the water. A bullet had come from the second canoe, also, but it flew wild, and then the whitish fog, thick and impenetrable, caught by a contrary current of wind, closed in again.

“Did you hit anything, Sol?” asked Henry.

“Only a canoe, but I busted it all up, an’ they’re swimmin’ from tree to tree until they get to the bank.”

“Now, boys, pull with all your might!” exclaimed Henry, “and, Paul, you steer us clear of trees, brush, logs, and snags. They know where we are and we must get out into the stream, where there’s a chance for our escape.”

Then ensued a flight and running combat in a tricky fog that lifted and closed down over and over again. Henry put down his oars presently and took up his rifle, but Jim Hart and Tom Ross continued to pull, and Paul kept a steady hand on the tiller.

Paul’s task was the most trying of all. Highly sensitive and imaginative, this battle rolling along in alternate dusky light and white obscurity, was to him uncanny and unreal. He saw pink dots of rifle fire in the fog, he caught glimpses now and then of brown, savage faces or the prow of a canoe, and then the heavy fog would come down like a blanket again, shutting out everything.

Paul’s hand trembled. Every nerve in him was jumping, but he resolutely steered the boat while the others rowed and fought. Once he barely grazed a snag and he shivered, knowing how one of these terrible obstructions could rip the bottom out of a boat. But soon the trees and bushes almost disappeared. They were coming into open water. The fog, too, ceased to close down, and the wind began to blow steadily out of the north. Banks and streamers of white vapor rolled away toward the south. In a few minutes it would all be gone. Out of the mists behind them rose the shapes of war canoes not far away, and the fierce triumphant yell that swept far over the river sent a chill to Paul’s very marrow. Once again rose the rifle fire, and it was now a rapid and steady crackle, but the bullets thudded in vain on the thick sides of “The Galleon.”

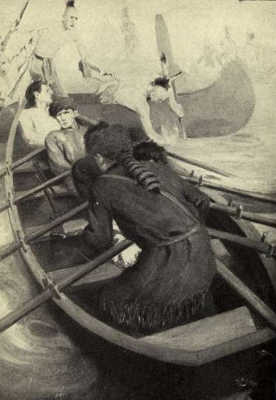

All except Paul now pulled desperately for the middle of the stream, while he, bending as low as he could, still kept a steady hand on the tiller. The triumphant shout behind them rose again, and the great stream gave it back in a weird echo. Paul suddenly uttered a gasp of despair. Directly in front of them, not thirty yards away, was a large war canoe, crowded with a dozen savages while behind them came the horde.

“What is it, Paul?” asked Henry.

“A big canoe in front of us full of warriors. We’re cut off! No, we’re not! I have it! Bend low! bend low, you fellows, and pull with all the might that’s in you!”

Paul had an inspiration, and his blood was leaping. The rifle shots still rattled behind them, but, as usual, the bullets buried themselves in the wood with a sigh, doing no harm. Four pairs of powerful arms and four powerful shoulders bent suddenly to their task with new strength and vigor. Paul’s words had been electric, thrilling, and every one felt their impulse instantly. The prow of the heavy boat cut swiftly through the water, and Paul bent still lower to escape the rifle-shots. No need for him to choose his course now! The boat was already sent upon its errand.

A wild shout of alarm rose from the war canoe, and the next instant the prow of “The Galleon” struck it squarely in the middle. There were more shouts of alarm or pain, a crunching, ripping and breaking of wood, and then “The Galleon,” after its momentary check, went on. The war canoe had been cut in two, and its late occupants were swimming for their lives. Not in vain had Paul read in an old Roman history of the battles between the fleets when galley cut down galley.

Henry, although he did not look up, knew at once what had happened, and he could not restrain admiration and praise.

“Good for you, Paul!” he cried. “You took us right over the war canoe and that’s what’s likely to save us!”

Henry was right. The other canoes, appalled by the disaster, and busy, too, in picking up the derelicts, hung back. Henry and Shif’less Sol took advantage of the opportunity, and sent bullet after bullet among them, aiming more particularly at the light bark canoes. Three filled and began to sink and their occupants had to be rescued. The utmost confusion and consternation reigned in the savage fleet, and the distance between it and “The Galleon” widened rapidly as the latter bore in a diagonal course across the Mississippi.

“They’ve had all they want,” said Henry, as he laid down his rifle and took up the oars again, “but it’s this big heavy boat that’s saved us. She’s been a regular floating fort.”

“We took our gall-yun just in time,” said Shif’less Sol jubilantly, “an’ she is shore the greatest warship that ever floated on these waters. Oh, she’s a fine boat, a beautiful boat, the reg’lar King o’ the seas!”

“Queen, you mean,” said Paul, who felt the reaction.

“No, King it is,” replied Sol stoutly. “A boat that carries travelers may be a she, but shorely one that fights like this is a he.”

The fog was gone, save for occasional wisps of white mist, but the day had not yet come, and the night was by no means light. When they looked back again they could not see any of the Indian canoes. Apparently they had retreated into the flooded forest. Henry and Sol held a consultation.

“It’s hard to pull up stream,” said Henry, “and we’d exhaust ourselves doing it. Besides, if the Indians chose to renew the pursuit, that would cut us off from our own purpose. We must drop down the river toward the Spanish camp.”

“You’re always right, Henry,” said the shiftless one with conviction. “The Spaniards o’ course, know nothin’ about our fight, ez they wuz much too fur off to hear the shots, an’, ez we go down that way, the savages likely will think that we belong to the party, which is too strong for them to attack. This must be some band that Braxton Wyatt don’t know nothin’ about. Maybe it’s a gang o’ southern Indians that’s come away up here in canoes.”

The boat swung close to the western shore, which was overhung throughout by heavy forests, and then dropped silently down until it came within two miles of the Spanish camp. There, in a particularly dark cove, they tied up to a tree, and drew mighty breaths of relief. Both Henry and Paul felt an intense gladness. Despite all the dangers and hardships through which they had gone, they were but boys.