8 The Mountain Ram

It snowed for two days and two nights without ceasing, and then turned so cold that the snow froze over, a covering like glass forming upon it. Will broke a way to the stable, where he talked to the animals and fed them with the hay which had been cut with forethought. With the help of the others he also opened a path down to a little stream flowing into the lake, where the horses and mules were able to obtain water, spending the rest of the time in the cavern.

The men usually had a small fire and they passed the time while they were snowed in in jerking more meat, repairing their clothes and doing a hundred other things that would be of service later on. Brady stored his traps in a remote corner of the cavern, hiding them so artfully that it was not likely anyone save the four would ever find them.

“I shall have no further use for them for a long time,” he said, “but after we reach our gold I mean to return here and get them.”

Will, who noticed his grammatical and good English, rather unusual on the border, asked him how he came to be a fur hunter.

“Drift,” he replied. “You would not think it, but it was my original intention to become a schoolmaster. An excursion into the west made me fall in love with the forest, the mountains, solitude and independence. I’ve always taken enough furs for a good living, and I’m absolutely my own master. Moreover, I’m an explorer and it gives me a keen pleasure to find a new river or a new mountain. And this northwest is filled with wonders. After we find the gold and my beaver colony, I’m going to write a book of a thousand pages about the wonders I’ve seen.”

“I never saw anybody that wrote a book,” said the Little Giant with the respect of the unlettered for the lettered, “an’ I confess I ain’t much of a hand at readin’ ’em, but when I’m rich ez I expect to be a year or two from now, an’ I build my fine house in St. Looey, I mean to have a room full of ’em, in fine leather an’ morocco bindin’s.”

“Will you read them?” asked Will.

“Me read ’em! O’ course not!” replied the Little Giant. “I’ll hire a man to read ’em, an’ he kin keep busy on them books while I’m away on my long huntin’ trips.”

“But that won’t be you reading ’em.”

“What diff’unce does that make? All a book asks is to be read by somebody, en’ ef it’s read by my reader ’stead o’ me it’s jest the same.”

The days confirmed them in their choice of Brady as the fourth partner in the great hunt. Despite his rather stern and solemn manner he was at heart a man of most cheerful and optimistic temperament. He had, too, a vast fund of experience and he knew much of the wilderness that was unknown to others.

“What do you think of our plan of going straight ahead as soon as we can travel, and passing over the left shoulder of the White Dome?” asked Boyd.

“It’s wisest,” replied Brady thoughtfully. “I’ve heard something of this Felton, with whom you had such a sanguinary encounter, and I’m inclined to think from all you tell me that he has had a hint about the mine. He has affiliated with the Indians and he can command a large band of his own, white men, mostly murderous refugees from the border, and the worst type of half breeds. It’s better for us to keep as long as we can in the depths of the mountains despite all the difficulties of travel there.”

On the fifth day it turned much warmer and rained heavily, and so violent were the changes in the high mountains that there was a tremendous manifestation of thunder and lightning. They watched the display of electricity with awe from the door of the cavern, and Will saw the great sword blades of light strike more than once on the rocks of the topmost peaks.

“I think,” said Brady devoutly, “that we have been watched over. Where else in the mountains could we have found such a refuge for our animals and ourselves?”

“Nowhere,” said the Little Giant, cheerfully, “an’ I want to say that I’m enjoyin’ myself right here. We four hev got more o’ time than anythin’ else, an’ I ain’t goin’ to stir from our nice, comf’table home ’til the travelings good.”

The others were in full agreement with him, and, in truth, delay was absolutely necessary as a march now would have been accompanied by new and great dangers, snow slides, avalanches, and the best of the paths slippery with mud and water. When the rain ceased, although a warm sun that followed it hastened the melting of the snow, Will released the animals from the stable and with pleasure saw them run about among the trees, where the snow had melted and sprigs of hardy grass were again showing green against the earth. After they had drunk at the lake and galloped up and down awhile, they began to nibble the grass, while Will walked among them and stroked their manes or noses, and was as pleased as they were. Brady’s three horses were already as firm friends of his as the earlier animals.

“Did you ever notice that boy’s ways with hosses an’ mules?” said the Little Giant to Brady. “He’s shorely a wonder. I think he’s got some kind o’ talk that we don’t understand but which they do. My critters and Boyd’s would quit us at any time fur him, an’ so will yours.”

“I perceive it is true, my friend, and so far as my horses are concerned I don’t grudge him his power. Now that the snow has gone and the greenness is returning this valley truly looks like the land of Canaan. And it is well for us to be outside again. People who live the lives that we do flourish best in the open air.”

The warm days lasted and all the snow melted, save where it lay perpetually on the crest of the White Dome. Often they heard it thundering in masses down the slopes. The whole earth was soaked with water, and swift streams ran in every gulch and ravine and canyon. Will, although he was impatient to be up and away, recognized now how thoroughly necessary it was to wait. The mountains in such a condition were impassable, and the valley was safe, too, because for the time nobody could come there either.

Big game wandered down again and Brady shot another large grizzly bear, the skin of which they saved and tanned, thinking it might prove in time as useful as the first. Another deer was added to their larder, and they also shot a number of wild fowl. But as the hills began to dry their minds returned with increasing strength to the great mine, hidden among far-away peaks. All were eager to be off, and it was only the patience coming from experience that delayed the start.

The valley dried out rapidly. The snow, deep as it had been, did not seem to have done any harm to the grass, which reappeared fresher and stronger than ever, forming a perfect harvest for the horses and mules. Then the time for departure came and they began to pack, having added considerably to their stores of skins and cured meats.

Brady also had been exceedingly well equipped for a long journey, and the temporary abandonment of his traps gave them a chance to add further to their food supplies. All four of them, in addition to their food, carried extra weapons, including revolvers, rifles, and a fine double-barreled shotgun for every one. The two caverns, the one for the men and the other for the horses, they left almost as they had fitted them up.

“We may come here ag’in,” said the Little Giant. “It’s true that Felton’s men an’ the Sioux also may come, but I don’t think it’s ez likely, ’cause the Sioux are mostly plains warriors, an’ them that ain’t are goin’ down thar anyhow to fight, while the outlaws likely are ridin’ to the west huntin’ fur us.”

“Anyway,” said Stephen Brady, in his deep, bass voice, “we’ll trust to Providence. It’s amazing how events happen in your favor when you really trust.”

Although eager to be on their way, they felt regret at leaving the valley. It had given them a snug home and shelter during the storm, and the melting of the snow had acted like a gigantic irrigation scheme, making it greener and fresher than before. As they climbed the western slope it looked more than ever a gem in its mountain setting. Will saw far beneath him the blue of lake and the green of grass, and he waved his hand in a good-bye, but not a good-bye forever.

“I expect to sleep there again some day,” he said.

“It’s a fine home,” said Brady, “but we’ll find other lakes and other valleys. As I have told you before, I have trapped for years through these regions, and they contain many such places.”

They pressed forward three more days and three more nights toward the left shoulder of the White Dome, which now rose before them clear and dazzlingly bright against the shining blue of the sky. The air was steadily growing colder, owing to their increasing elevation, but they had no more storms of rain, sleet or snow. They were not above the timber line, and the vegetation, although dwarfed, was abundant. There was also plenty of game, and in order to save their supplies they shot a deer or two. On the third day Will through his glasses saw a smoke, much lower down on their left, and he and the Little Giant, descending a considerable distance to discover what it meant, were able to discern a deep valley, perhaps ten miles long and two miles broad, filled with fine pastures and noble forest, and with a large Indian village in the centre. Smoke was rising from at least a hundred tall tepees, and several hundred horses were grazing on the meadows.

“Tell me what you can about them,” said the lad, handing the glasses to the Little Giant.

“I think they’re Teton Sioux,” said Bent, “an’ ez well ez I kin make out they’re livin’ a life o’ plenty. I kin see game hangin’ up everywhar to be cured. Sometimes, young William, I envy the Indians. When the weather’s right, an’ the village is in a good place an’ thar’s plenty to eat you never see any happier fellers. The day’s work an’ huntin’ over, they skylark ’roun’ like boys havin’ fun with all sorts o’ little things. You wouldn’t think they wuz the same men who could enjoy roastin’ an enemy alive. Then, they ain’t troubled a bit ’bout the future, either. Termorrer kin take care o’ itself. I s’pose that’s what downs ’em, an’ gives all the land some day to the white man. Though I hev to fight the Indian, I’ve a lot o’ sympathy with him, too.”

“I feel the same way about it,” said Will. “Maybe we won’t have any more trouble with them.”

The Little Giant shook his head.

“We may dodge ’em in the mountains, though that ain’t shore,” he said, “but when we go down into the plains, ez we’ve got to do sooner or later, the fur will fly. I’m mighty glad we picked up Steve Brady, ’cause fur all his solemn ways he’s a pow’ful good fightin’ man. Now, I think we’d better git back up the slope, ’cause warriors from that village may be huntin’ ’long here an’, however much we may sympathize with the Indians we’re boun’ to lose a hull lot o’ that sympathy when they come at us, burnin’ fur our scalps.”

“Correct,” laughed Will, and as fast as they could climb they rejoined the others, telling what they had seen. Brady showed some apprehension over their report.

“I’ve noticed that mountain sheep and goats are numerous through here, and while Indians live mostly on the buffalo, yet they have many daring hunters in the mountains, looking for goats and sheep, and maybe in the ravines for the smaller bears, the meat of which they love.”

“And you think we may be seen by some such hunters?” said Will.

“Perhaps so, and in order to avoid such bad luck I suggest that we seek still greater height.”

They agreed upon it, though the Little Giant grumbled at the hard luck that compelled them to scale the tops of high mountains, and they began at once a perilous ascent, which would not have been possible for the horses had they not been trained by long experience. They also entered a domain of bad weather, being troubled much by rain, heavy winds and occasional snows, and at night it was so cold that they invariably built a fire in some ravine or deep gully. Will calculated that they were at least ten thousand feet above the sea level, and that the White Dome, which was now straight ahead, must be between three and four thousand feet higher. They reckoned that they could circle the peak on the left at their present height, and they made good progress, as there seemed to be fewer ravines and canyons close to the dome.

Nevertheless, as they approached they came to a dip much deeper than usual, but it was worth the descent into it, as they found there in the sheltered spaces plenty of grass for the horses, and they were quite willing to rest also, as every nerve and muscle was racked by the mountain climbing. Still holding that time was their most abundant possession, the hunter suggested that they spend a full day and night in the dip, and all the others welcomed the idea.

Will, being younger than the others, had more physical elasticity, and a few hours restored him perfectly. Then he decided to take his rifle and go up the dip looking for a mountain sheep, and the others being quite willing, he was soon making his way through the short bushes toward the north. He prided himself on having become a good hunter and trailer, and even here in the heart of the high mountains he neglected no precaution.

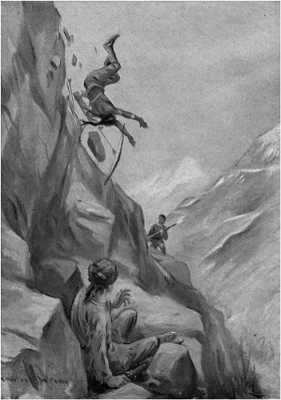

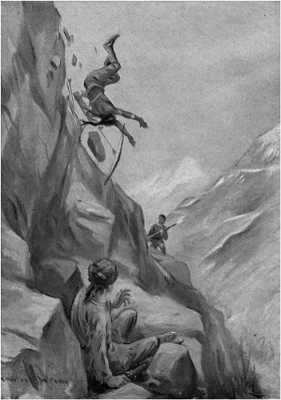

The dip extended about two miles into the north and then it began to rise rapidly, ending at last in huge, craggy rocks, towering a thousand feet overhead, and Will considered himself in great luck when he saw a splendid ram standing upon one of these stony pinnacles.

The sheep, sharply outlined against the rock and the clear sky, looked at least double his real size, and Will, anxious to procure fresh game, and feeling some of the hunter’s ambition, resolved to stalk him. The animal reminded him of a lookout, and perhaps he was, as he stood on his dizzy perch, gazing over the vast range of valley, and the White Dome that now seemed so near.

The lad reached the first rocky slope and began slowly to creep in a diagonal line that took him upward and also toward the sheep. It was difficult work to keep one’s footing and carry one’s rifle also, but his pride was up and he clung to his task, until his muscles began to ache and the perspiration came out on his face. He was in fear lest the sheep would go away, but the great ram stood there, immovable, his head haughtily erect, a monarch of his tribe, and Will became thoroughly convinced that he was a watchman.

His repeating rifle carried a long distance, but he did not want to make an uncertain shot, and he continued his laborious task of climbing which yielded such slow results. The sheep took no notice of him, still gazing over valley and ranges and at the White Dome. If he saw him, the lad was evidently in his eyes a speck in a vast world and not worth notice. Will felt a sort of chagrin that he was not considered more dangerous, and, patting his rifle, he resolved to make the ram realize that a real hunter was after him.

He crawled painfully and cautiously around a big rock and something whirring by his ear rang sharply on the stone. He saw to his amazement a long feathered arrow dropping away from the target on which it had struck in vain, and then roll down the side of the mountain.

He knew, too, that the arrow had passed within a few inches of his ear, aimed with deadly purpose, and for a moment or two his blood was cold within his veins. Instantly he turned aside and flattened himself against a stony upthrust. As he did so he heard the ring on the rock again and a second feathered arrow tumbled into the void.

His first emotion was thankfulness. He lay in a shallow hollow now and it was not easy for any arrow to reach him there. He was unharmed as yet, and he had the great repeating rifle which should be a competent answer to arrows. Some loose stones were lying in the hollow, and he cautiously built them into a low parapet, which increased his protection. Then, peeping over the stones, he tried to discover the location of his enemy or enemies, if they should be plural, but he saw only the valley below with its touch of sheltered green, the vast rocky sides about it, and over all the towering summit of the White Dome. There was nothing, save the flight of the feathered arrows, to indicate that a human being was near. Far out on the jutting crag the mountain sheep still stood, a magnificent ram, showing no consciousness of danger or, if conscious of it, defying it. Will suddenly lost all desire to take his life, due, perhaps, to his own resentment at the effort of somebody to take his own.

He believed that the arrows had come from above, but whether from a point directly overhead or to the right or to the left he had no way of telling. It was a hidden foe that he had to combat, and this ignorance was the worst feature of his position. He did not know which way to turn, he did not know which road led to escape, but must lie in his narrow groove until the enemy attacked.

He had learned from his comrades, experienced in the wilderness and in Indian warfare, that perhaps the greatest of all qualities in such surroundings was patience, and if it had not been for such knowledge he might have risked a third arrow long ago, but, as it was, he kept perfectly still, flattening himself against the cliff, sheltered by the edge of the natural bowl and the little terrace of stones he had built. He might have fired his rifle to attract the attention of his comrades, but he judged that they were at the camp and would not hear his shot. He would fight it out himself, especially as he believed that he was menaced by but a single Indian, a warrior who perhaps had been stalking the mountain sheep also, when he had beheld the creeping lad.

Great as was the strength of the youth’s will and patience, he began to twist his body a little in the stony bowl and seek here and there for a sight of his besieger. He could make out stony outcrops and projections above him, every one of which might shelter a warrior, and he was about to give up the quest when a third arrow whistled, struck upon the ledge that he had built and, instead of falling into the chasm, rebounded into the bowl wherein he lay.

The barb had been broken by the rock against which it struck so hard, though the shaft, long, polished and feathered, showed that it had been made by an artist But he did not know enough about arrows to tell whether it was that of a Sioux or of a warrior belonging to some other tribe. Looking at it a little while, he threw it into the chasm, and settled back to more waiting.

The day was now well advanced and a brilliant sun in the slope of the heavens began to pour fiery shafts upon the side of the cliff. Will had usually found it cold at such a height, but now the beams struck directly upon him and his face was soon covered with perspiration. He was assailed also by a fierce, burning thirst, and a great anger lay hold of him. It was a terrible joke that he should be held there in the hole of the cliff by an invisible warrior who used only arrows against him, perhaps because he feared a shot from a rifle would bring the white lad’s comrades.

If the Indian would not use a rifle because of the report, then the case was the reverse with Will. He had thought that the men were too far away to hear, but perhaps the warrior was right, and raising the repeating rifle he sent a bullet into the void. The sharp report came back in many echoes, but he heard no reply from the valley. A second shot, and still no answer. It was evident that the three were too distant to hear, and, for the present, he thought it wise to waste no more bullets.

The power of the sun increased, seeming to concentrate its rays in the little hollow in which Will lay. His face was scorched and his burning thirst was almost intolerable. Yet he reflected that the heat must be at the zenith. Soon the sun would decline, and then would come night, under the cover of which he might escape.

He heard a heavy, rolling sound and a great rock crashed into the valley below. Will shuddered and crowded himself back for every inch of shelter he could obtain. A second rock rolled down, but did not come so near, then a third bounded directly over his head, followed quickly by another in almost the same place.

It was a hideous bombardment, but he realized that so long as he kept close in his little den he was safe. It also told him that his opponent was directly above him, and when the volleys of rocks ceased he might get a shot.

The missiles poured down for several minutes and then ceased abruptly. Evidently the warrior had realized the futility of his avalanche and must now be seeking some other mode of attack. It caused Will chagrin that he had not seen him once during all the long attack, but he noticed with relief that the sun would soon set beyond the great White Dome. The snow on the Dome itself was tinged now with fire, but it looked cool even at the distance, and assuaged a little his heat and thirst. He knew that bye and bye the long shadows would fall, and then the grateful cold of the night would come.

He moved a little, flexed his muscles, grown stiff by his cramped position, and as he did so he caught a glimpse of a figure on the south face of the wall. But it was so fleeting he was not sure. If he had only brought his glasses with him he might have decided, but he was without them, and he concluded finally that it was merely an optical illusion. He and the Indian had the mountain walls to themselves, and the warrior could not have moved around to that point.

In spite of his decision his eyes at length wandered again to that side of the wall, and a second time he thought he caught a glimpse of a human figure creeping among the rocks, but much nearer now. Then he realized that it was no illusion. He had, in very truth, seen a man, and as he still looked a rifle was thrust over a ledge, a puff of fire leaping from its muzzle. From a point above him came a cry that he knew to be a death yell, and the body of a warrior shot downward, striking on the ledges until it bounded clear of them and crashed into the valley below.

Then the figure of the man who had fired the shot stepped upon a rocky shelf, held aloft the weapon with which he had dealt sudden and terrible death, and cried in a tremendous voice:

“Come forth, young William! Your besieger will besiege no more! Ef I do say it myself, I’ve never made a better shot.”

It was the Little Giant. Never had the sight of him been more welcome, and raising himself stiffly to his feet and moving his own rifle about his head, Will shouted in reply:

“It was not only your greatest shot, but the greatest shot ever made by anybody.”

“Stay whar you are,” cried Bent. “You’re too stiff an’ sore to risk climbin’ jest yet. I’ll be with you soon.”

But it was almost dark before the Little Giant crept around the face of the cliff and reached the hollow in which the lad lay. Then he told him that he had seen some of the rocks falling and as he was carrying Will’s glasses he was able to pick out the warrior at the top of the cliff. The successful shot followed and the siege was over.

Night had now come and it was an extremely delicate task to find their way back to the valley, but they made the trip at last without mishap. Once again on level ground Will was forced to sit down and rest until a sudden faintness passed. The Little Giant regarded him with sympathy.

“You had a pretty tough time, young William, thar’s no denyin’ that,” he said. “It’s hard to be cooped up in a hole in a mountainside, with an enemy shootin’ at you an’ sendin’ avalanches down on you, an’ you never seein’ him a-tall.”

“I never saw him once until he plunged from the cliff with your bullet through him.”

“Wa’al, it’s all over now, an’ we’ll go back to the camp. The boys had been worryin’ ’bout you some, and I concluded I’d come out an’ look fur you, an’ ef it hadn’t been fur my concludin’ so I guess you’d been settin’ thar in that holler a month from now, an’ the Indian would hev been settin’ in a holler above you. At least I hev saved you from a long waitin’ spell.”

“You have,” said Will with heartfelt emphasis, “and again I thank you.”

“Come on, then. I kin see the fire shinin’ through the trees an’ Jim an’ Steve cookin’ our supper.”

Will hurried along, but his knees grew weak again and objects swam before his eyes. He had not yet recovered his strength fully after passing through the tremendous test of mental and physical endurance, when he lay so long in that little hollow in the side of the mountain. The Little Giant was about to thrust out a hand and help sustain him, but he did not do so, remembering that it would hurt the lad’s pride. The gold hunter, uneducated, spending his life in the wilds, had nevertheless a delicacy of feeling worthy of the finest flower of civilization.

Will was near to the fire now and the pleasant aroma of broiling venison came to him. Boyd and Brady were moving about the flames, engaged in pleasant homely tasks, and all his strength returned. Once more his head was steady and his muscles strong.

“I made a long stay,” he called cheerfully to them, “too long, I fear, nor do I bring a mountain sheep back with me.”

The sharp eyes of the hunter and the trapper saw at once in his pallid face and exaggerated manner that something unusual had happened, but they pretended to take no notice.

“Did you see any sheep?” asked Boyd.

“Yes,” replied the lad, “I had a splendid view of a grand ram, standing high on a jutting stone over the great valley.”

“What became of him?”

“I don’t know. I became so busy with something else that I forgot all about him, and he must have gone away in the twilight. An Indian in a niche above me began firing arrows at me, and I had to stick close in a little hollow in the stone so he couldn’t reach me. If the Little Giant hadn’t come along, and made another of his wonderful shots I suppose I’d be staying there for a week to come.”

“Tom can shoot a little,” said Boyd, divining the whole story from the lad’s few sentences, “and he also has a way of shooting at the right time. Now, you sit down here, Will, and eat these steaks I’m broiling, and I’ll give you a cup of coffee, too, just one cup though, because we’re sparing our coffee as much as we can now.”

Will ate and drank with a great appetite, and then he told more fully of his adventure with the foe whom he had never seen until the Little Giant’s bullet sent him spinning into the void.

“He’d have got you,” said Brady thoughtfully, “if Tom hadn’t come along.”

“You know we wuz worried ’bout him stayin’ so long,” said the Little Giant, “an’ so I went out to look fur him. It wuz lucky that I took his glasses along, or I might never hev seen him or the Sioux. I don’t want to brag, but that wuz one o’ my happy thoughts.”

“You had nothing to do with taking the glasses, Tom Bent,” said Brady seriously.

“Why, it wuz my own idee!”

“Not at all. The idea was in your head but it was not put there by your own mind. It was put there by the Infinite, and it was put there because Will’s time had not yet come. You were merely an instrument, Tom Bent.”

“Mebbe I wuz. I’m not takin’ any credit to myself fur deep thinkin’ an’ I ’low you know more ’bout these things than I do, Steve Brady, since you’ve had your mind on ’em so much an’ so long. An’ ef I wuz used ez an instrument to save Will, I’m proud that it wuz so.”

Will, who was lying on the turf propped up by his elbow before the fire, looked up at the skies, which were now a clear silver, in which countless stars appeared to hang, lower and larger than he had ever seen them before. It was a beautiful sky, and whether it was merely fate or chance that had sent the Little Giant to his aid he felt with the poet that God was in his heaven, and, for the time at least, all was right with his world.

“You got a good sight of the Indian, did you, Tom?” asked Boyd.

“I saw him plain through the glasses. He wuz a Sioux. I couldn’t make no mistake. Like ez not he wuz a hunter from the village we saw on the slope below, an’ whar one hunter is another may not be fur away.”

“Thinking as you do,” said Boyd, “and thinking as I do the same way you do, I think we’d better put out our fire and shift to another part of the valley.”

“That’s a lot of ‘thinks,’” said Brady, “but it seems to me that you’re both right, and I’ve no doubt such thoughts are put into our minds to save our lives. Perhaps it would be best for us to start up the slopes at once, but if our time is coming tonight it will come and no flight of ours will alter it.”

Nevertheless they took the precaution to stamp out the last coal, and then moved silently with the animals to another part of the dip. While they were tethering their horses and mules there in a little glade all the animals began to tremble violently and it required Will’s utmost efforts to soothe them. The acute ears of Brady detected a low growling on their right, not far from the base of the cliff.

“Come, Tom,” he said to the Little Giant. “You and I will see what it is, and be sure you’re ready with that rifle of yours. You ought to shoot beautifully in this clear moonlight.”

They disappeared among the bushes, but returned in a few minutes, although the growling had become louder and was continuous. Both men had lost a little of their ruddiness.

“What was it?” asked Will.

“It wuz your friend, the Sioux warrior who held you in the cliff so long,” replied the Little Giant, shuddering. “Half a dozen big mountain wolves are quarrelin’ ’bout the right place to bury him in. But, anyway, he’s bein’ buried, an’ mighty fast too.”

Will shuddered also, and over and over again. In fact, his nervous system had been so shaken that it would not recover its full force for a day, and the others, trained to see all things, noticed it.

“You soothe them animals ag’in, young William,” said the Little Giant, “an’ we’ll spread the blankets fur our beds here in the bushes.”

Bent again showed supreme judgment, as in quieting the fears of the horses and mules for the second time Will found that renewed strength flowed back into his own nervous system, and when he returned to the fireless camp his hand and voice were once more quite steady.

“There is your bed, William,” said Brady. “You lie on one blanket, put the other over you, and also one of the bearskins. It’s likely to be a dry and cold night, but anyway, whether it rains or snows, it will rain or snow on the just and the unjust, and blankets and bearskin should keep you dry. That growling in the bushes, too, has ceased, and our friend, the Sioux, who sought your life, has found a dreadful grave.”

Will shuddered once more, but when he crept between the blankets his nerves were soothed rapidly and he soon fell asleep.

The three men kept watch and watch through the night, and they saw no Indian foe. Once Boyd heard a rustling in the bushes, and he made out the figure of a huge mountain wolf that stood staring at them for a moment. The horses and mules began to stir uneasily, and, picking up a stone, the hunter threw it with such good aim that the wolf, struck smartly on the body, ran away.

The animals relapsed into quiet, and nothing more stirred in the bushes, until the leaves began to move under the light breeze that came at dawn.