12 The Captive’s Rise

Will did not know just how long they had been traveling, having lost count of the days, but he knew they had come an immense distance, perhaps a thousand miles, maybe more, because the hardy Indian ponies always went at a good pace, and he felt that the distance between him and every white settlement must be vast.

The sun at first hurt the eyes that had been bandaged so long in daylight, but as the optic nerves grew less sensitive and they could take in all the splendor of the world, he had never before seen it so beautiful. He was like one really and truly blind for years who had suddenly recovered his sight. Everything was magnified, made more vivid, more intense, and his joy, captive though he was, was so keen that he could not keep from showing it.

“You find it pleasant to live,” said Heraka.

“Yes,” replied the lad frankly, “I don’t mind admitting to you that I like living. And I like seeing, too, in the bright sunshine, when I’ve been so long without it. You warned me, Heraka, that I would not know my fate, nor whence nor when it might come, but instinct tells me that it’s not coming yet, and as one who can see again I mean to enjoy the bright days.”

“Wayaka is but a youth. If he were older he would fear more.”

“But I’m not older. This, I suppose, is where we mean to stay awhile?”

“It is. It is one of our hidden valleys. Beyond the stretch of forest is a Sioux village, and there you will stay until your fate befalls you.”

“I imagine, Heraka, that you did not come here merely to escort me. So great a chief would not take so long a ride for one so insignificant as I am. You must have had another motive.”

“Though Wayaka is a youth he is also keen. It is part of a great plan, of which I will tell you nothing, save that the Sioux are a mighty nation, their lands extending hundreds of miles in every direction, and they gather all their forces to push back the whites.”

“Then your long journey must be diplomatic. You travel to the farthest outskirt in order to gather your utmost forces for the conflict.”

Heraka smiled rather grimly.

“Wayaka may be right,” he said. “He is a youth of understanding, but in the village beyond the wood you are to stay until you leave it, but you will not know in what manner or when you will depart from it.”

Will inferred that his departure might be for the happy hunting grounds rather than for some other place, but it could not depress him. He was too much suffused with joy over his release from his long blindness and with the splendor of the new world about him to feel sadness. For a while nothing can weigh down the blind who see again. It was surely the finest valley in the world into which they had come!

Heraka gave the word and he and his men rode forward toward the strip of wood that he had indicated. All the ponies, although strong and wiry, were thin and worn by their long journey, and some of the Indians, despite their great endurance, showed signs of weariness. Little as they displayed emotion, their own eyes had lighted up at sight of the pleasant place into which they had come.

Will could not tell the length of the valley owing to its curving nature, but he surmised that it might possibly be twenty miles, with a general average width of perhaps two or three. All around it were high mountains, and on the distant and loftier ones the snow line seemed to come further down than on those he had seen with his comrades. Quick to observe and to draw conclusions the fact was another proof to him that they had been traveling mostly north. The trees in the valley were chiefly of the coniferous type, fir, pine and spruce. Despite the warmth of the air all things wore for him a northern aspect, but he made no comment to Heraka.

They reached the strip of wood, and one of the warriors uttered a long cry that was answered instantly from a point not far ahead. Then young Indian lads came running, welcoming them with shouts of joy, and, with this escort, they rode into the village, which was well placed in a grassy opening in the very center of the forest.

Will saw an irregular collection of about a hundred tepees, all conical, most of them made from the skin of the buffalo, though in some cases the hides of bear and elk had been used. All were supported on a framework of poles stripped of their bark. The poles were about twenty feet in length, fastened in a circle at the bottom and leaning toward a common center, where they crossed at a height of twelve or thirteen feet. The diameter of the tepees at the bottom was anywhere from fifteen to twenty feet, and hence they were somewhat larger than the usual Sioux lodges.

All the tepees had an uncommon air of solidity, as if the poles that made their framework were large, strong, and thrust deep in the earth. The covering skins were sewed together with rawhide strings as tight and secure as the work of any sailor. One seam reaching about six feet from the ground was left open and this was the doorway, over which a buffalo hide or other skin could be lashed in wintry or stormy weather.

At present all the tepees were open, and Will saw many squaws and children about. Just beyond the village and at the edge of the forest ran a considerable creek, evidently fed by the melting snows on the high mountains, and, on extensive meadows of high grass beyond the creek, grazed a great herd of ponies, fat and in good condition. Will decided at once that it was a village of security and abundance. The mountains must be filled with game, and the creek was deep enough for large fish.

He had been left unbound as they descended into the valley and, deciding that he must follow a policy of boldness, he leaped off the pony when they entered the village, just as if he were coming back home. But the old squaws and the children did not give him peace. They crowded around him, uttering cries that he knew must be taunts or jeers. Then they began to push and pull him and to snatch at his hair. Finally an old squaw thrust a splinter clean through his coat and into his arm. The pain was exquisite, but, turning, he took her chin firmly in one hand and with the other slapped her cheeks so severely that she would have fallen to the ground if it had not been for the detaining grasp on her chin.

The crowd, with the instinct for the rough that dwells in all primitive breasts, roared with laughter, and Will knew that his bold act had brought him a certain measure of public favor. Heraka with a sharp word or two sent all the women and children flying, and then said in tones of great gravity to Will:

“Here you are to remain a prisoner, the prisoner of all the village, until we choose your fate. You will stay in a tepee with Inmutanka, but everybody will watch you, the men, the women, the girls and the boys. Nothing that you do can escape their notice, and you will not have the slightest chance of flight.”

“If I am to be anybody’s guest,” said Will, “I’d choose to be old Dr. Inmutanka’s. He has a soul in his body.”

“You are not a guest, you are a slave,” said Heraka.

Will did not appreciate the full significance of his words then, because Inmutanka was showing the way to one of the smaller tepees and he entered it, finding it clean and commodious. The ground was covered with bark, over which furs and skins were spread and there was a place in the center for a fire, the smoke to ascend through a triangular opening in the top, where it was regulated by a wing worked from the outside.

Inmutanka, who undoubtedly had a kind heart, pointed to a heap of buffalo robes in the corner, and Will threw himself upon them. All the enormous exhaustion of such a tremendous journey suddenly became cumulative and he slept until Inmutanka awoke trim a full fifteen hours later. Then he discovered that the old Indian really knew a little English, though he had hidden the fact before.

“You eat,” he said, and gave him fish, venison and some bread of Indian corn, which Will ate with the huge appetite of the young and strong.

“Now you work,” said Inmutanka, when he had finished.

Will stared at him, and then he remembered Heraka’s words of the day before that he was a slave. He was assailed by a sickening sensation but he pulled himself together bravely, and, having become a wise youth, he resolved that he would not make his fate worse by vain resistance.

“All right,” he said, “what am I to do?”

“You be pony herd now.”

“Well, that isn’t so bad.”

Inmutanka led the way across the creek, or rather river, and Will saw that the herd on the meadows was quite large, numbering at least a thousand ponies, and also many large American horses, captured or stolen. They grazed at will on the deep grass, but small Indian boys carrying sticks watched them continually. “You take your place here with boys,” said Inmutanka, “and see that ponies don’t run up and down valley.”

He gave him a stick and left him with the little Sioux lads. Will considered the task extremely light, certainly not one that had a savor of slavery, but he soon found that he was surrounded by pests. The Indian boys began to torment him, slipping up behind him, pulling his hair and then darting away again, throwing stones or clods of earth at him, and seeking to drive ponies upon him.

Will’s heart was suffused with anger. They were younger and smaller than he, but they had an infinite power to vex or cause pain. Nevertheless he clung to his resolution. He refused to show anger, and while it was by no means his disposition to turn one cheek when the other was smitten, he exhibited a patience of which he had not believed himself capable. He also showed a power that they did not possess. When some of the younger and friskier ponies sought to break away from the main herd and race up the river he soothed them by voice and touch and turned them back in such an amazing manner that the Indian boys brought some of the older warriors to observe his magic with horses.

Will saw the men watching, but he pretended not to notice. Nevertheless he felt that fate, after playing him so many bad tricks, was now doing him a good turn. He would exploit his power with animals to the utmost. Indians were always impressed with an unusual display of ability of any kind, and they felt that its possessor was endowed with magic. He walked freely among the ponies, which would have turned their heels on the Indian lads, and stroked their manes and noses.

The warriors went away without saying anything. The Indian boys returned to the village shortly after noon, but their place was taken by a fresh band, while Will remained on duty. Nor was he allowed to leave until long after twilight, when, surprised to find how weary he was, he dragged his feet to the tepee of Inmutanka, where he had venison, pemmican and water.

“Not so bad,” he said to the old Indian. “I believe I’m a good herd for ponies, though I’d rather do it riding than walking.”

“To-morrow you scrape hides with squaws,” said Inmutanka.

Will was disappointed, but he recalled that after the threat of Heraka he should not expect to get off with such an easy task as the continual herding of ponies. Scraping hides would be terribly wearying and it would be a humiliation to put him with the old squaws. Nevertheless his heart was light. The fate of the white captive too often was speedy and horrible torture and death. He felt that the longer they were delayed, less was the likelihood that he would ever have to suffer them at all.

He was awakened at dawn, and as soon as he had eaten he was put to his task. Fresh buffalo hides were stretched tightly and staked upon the ground, the inner side up, and he and a dozen old squaws began the labor of scraping from them the last particles of flesh with small knives of bone.

He cut his hands, his back ached, the perspiration streamed from his face, and the squaws, far more expert than he, jeered at him continually. Warriors also passed and uttered contemptuous words in an unknown language. But Will, clinging to his resolution, pretended to take no notice. Long before the day was over every bone in him was aching and his hands were bleeding, but he made no complaint. When he returned to the tepee Inmutanka put a lotion on his hands.

“It good for you, but must not tell,” he said.

“I wouldn’t dream of telling,” said Will fervently. “God bless you, Inmutanka. If there’s any finer doctor than you anywhere in the world I never heard of him.”

But he had to go back to the task of scraping the skins early in the morning, and for a week he labored at it, until he thought his back would never straighten out again. He recalled that first day with the pony herd. The labor there was heaven compared with that which he was now doing. Perhaps he had been wrong to show his power with animals: If he had pretended to be awkward and ignorant with horses they might have kept him there.

He made no sign, nor did he give any hint to Inmutanka that he would like a change. He judged, too, that he had inspired a certain degree of respect and liking in the old Indian who put such effective ointment on his hands every night that at the end of a week all the cuts and bruises were healed. Moreover, he had learned how to use the bone scrapers with a sufficient degree of skill not to cut himself.

But he was still a daily subject of derision for the warriors, women and children. It was the little Indian boys who annoyed him most, often trying to thrust splinters into his arms or legs, although he invariably pushed them away. He never struck any of them, however, and he saw that his forbearance was beginning to win from the warriors, at least, a certain degree of toleration.

When the scraping of the skins was finished he was set to work with some of the old men making lances. These were formidable weapons, at least twelve feet long, an inch to an inch and a half in diameter, ending in a two-edged blade made of flint, elk horn or bone, and five or six inches in length. The wood, constituting the body of the lance, had to be scraped down with great care, and the prisoner toiled over them for many days.

Then he began to make shields from the hide that grew on the neck of the buffalo, where it was thickest. When it was denuded of hair the hide was a full quarter of an inch through. Then it was cut in a circle two or two and a half feet in diameter and two of the circles were joined together, making a thickness of a full half inch. Dried thoroughly the shield became almost as hard as iron, and the bullet of the old-fashioned rifle would not penetrate it.

He also helped to make bows, the favorite wood being of osage orange, although pine, oak, elm, elder and many other kinds were used, and he was one of the toilers, too, at the making of arrows. Mounted on his wiry pony with his strong shield, his long lance, his powerful bow and quiver of arrows, the Sioux was a formidable warrior, and Will understood how he had won the overlordship of such a vast area.

A month, in which he was subjected to the most unremitting toil, passed, yet his spirit and body triumphed over it, and both grew stronger. He felt now as if he could endure anything and he knew that he would be called upon to endure much.

His youth and his plastic nature caused him to imitate to a certain extent, and almost unconsciously, the manners and customs of those around him. He became stoical, he pretended to an indifference which often he did not feel, and he never spoke of the friends who had disappeared so suddenly from his life, even to old Inmutanka. The “doctor,” as Will called him, was improving his English by practice, and Will in return was learning Sioux fast both from Inmutanka and from the people in the village. He knew the names of many animals. The buffalo was Pteha, the bear was Warankxi, the badger, Roka; the deer, Tarinca; the wolf, Xunktokeca.

One can get along with a surprisingly small vocabulary, and one also learns fast when he is surrounded by people who do not speak his own language. In six weeks Will had quite a smattering of the Sioux tongue. He still lived in the lodge of Inmutanka, who was invariably kind and helpful, and Will soon had a genuine liking for the good old doctor. It pleased him to wait upon Inmutanka as if he were a son.

It was, on the whole, well for the lad that he was compelled to work, because after the day’s labors were over and he had eaten his supper, he fell asleep from exhaustion, and slept without dreams. Thus he was not able to think as much as he would have done about his present condition, the great quest that he had been compelled to abandon, and those whom he had lost. Yet he could not believe, despite what Heraka had said, that Boyd, Brady and the Little Giant were lost. But he had many bitter moments. Often the humiliations were almost greater than he could bear, and it seemed that his quest was over forever.

These thoughts came most at night, but renewed courage would always reappear in the morning. He was too young, too strong, to feel permanent despair, and his body was growing so tough and enduring that, in his belief, if a time to escape ever came, he would be equal to it. But it was obvious that no such time was at hand. There were several hundred pairs of eyes in the village and he knew that every pair above five years of age watched him. Nothing that he did escaped their attention. Somebody was always near him, and, if he attempted flight, the alarm would be given before he went ten yards, and the whole village would come swarming upon him. So he wisely made no such trial, and seemed to settle down into a sort of content.

He saw no more then of Heraka, who had evidently gone away to the great war with the white men, But he saw a good deal of the chief of the village, an old man named Xingudan, which in Sioux meant the Fox. Xingudan’s face was seamed with years, though his tall figure was not bent, and Will soon learned that his name had been earned. Xingudan, though he seldom went on the war path now, was full of craft and guile and cunning. The village under his rule was orderly and more far-seeing than Indians usually are.

The Sioux began to strengthen their lodges and to accumulate stores of pemmican. The maize in several small, sheltered fields farther down the valley was gathered carefully. The boys brought in bushels of nuts, and Will admired the industry and ability of Xingudan. It was evident that winter was coming, although the touch as yet was only that of autumn.

It was a magnificent autumn that the lad witnessed. The foliage in the mountains glowed in the deepest and most intense colors that he had ever seen, reds, yellows, browns and shades between. Far up on the slopes he saw great splotches of color blazing in scarlet, and far beyond them in the north the white crests of dim and towering mountains. He was strengthened in his belief that he was far to the north of the fighting line, although his conclusion was based only upon his own observations. No Indian, not even a child, had ever spoken to him a word to indicate where he was. He inferred that silence upon that point had been enjoined and that old Xingudan would punish severely any infraction of the law. Even Inmutanka, so kind in other respects, would never give forth a word of information.

As the autumn deepened, the lad’s mind underwent another strange change, or perhaps it was not so strange at all. Youth must adapt itself, and he began to feel a certain sympathy and friendliness with the young Sioux of his own age. He also began to see wild life at its best, that is, under the circumstances most favorable to happiness.

The village was full of food, the hunting had never been better, and the forest had yielded an uncommon quantity of fruits and nuts. All the primitive wants were satisfied, and there was no sickness. After dark the youths of the village roamed about, playing and skylarking like so many white lads of their own age, but the girls as soon as the twilight came remained close in the lodges. Will saw a kind of happiness he had never looked upon before, a happiness that was wholly of the moment, untroubled by any thoughts of the future, and therefore without alloy. He saw that the primitive man when his stomach was full, and the shelter was good could have absolute physical joy. Strangely enough he found himself taking an interest in these pleasures, and by and by he began to share in them to a minor degree.

The river afforded a fine stretch of water, and the Indians had large canoes which they now used freely for purposes of sport. These boats were made of strong rawhide, generally about thirty feet long, although one was a full fifty feet, and they also had several boats shaped like huge bowls, made with a frame of wicker and covering it, the strongest buffalo hide, sewed together with unbreakable rawhide strings. They called these round boats watta tatankaha, which Will learnt meant in English bull boats. Just such boats as these were used on the Tigris, and the Euphrates, the oldest of rivers known to civilized man.

The first sign of relenting toward the captive lad was when he was allowed to withdraw from the hard work of strengthening a lodge to take a place alone in one of the bull boats and navigate it with a paddle down the river, at a place where it had a depth past fording. The stream was swift here and, despite his knowledge of ordinary curves, the round craft overturned with him before he had gone twenty feet, amid shouts of laughter from the Sioux gathered on either bank.

The water flowing down from the mountains was very cold, but Will scorned to cry for help. He was a powerful swimmer and he struck out boldly for the round boat, which was floating ahead. He had held on to the paddle all the while and, by a desperate struggle, he managed to right his craft and pull himself into it again. He was so much immersed in his physical struggle that he did not know the Indian children were pelting him with sticks and clods of earth, and were shouting in amusement and derision. But the warriors were grave and silent.

Another struggle and the round boat overturned again. But he held on to the paddle and recovered it a second time. A new and desperate contest between him and the boat followed, but in the end he was victor and paddled it both down and up-stream in a fairly steady manner. Then he brought it into the landing where he was received in a respectful silence.

In his struggles to succeed Will had taken little notice of the coldness of the waters, but when he went back to the lodge he had a severe chill, followed by a high fever. Then old Inmutanka proved himself the doctor that Will called him by using a remedy that either killed or cured.

Inmutanka gave the lad a sweat bath. He made a heap of stones and built a big fire upon them, feeding it until their heat was very great. Then he scraped away the fuel and put up a framework made of poles, covered with layers of skins. These layers were six or seven feet above the stones. Will was placed in a skin hammock under the layers and suspended about two feet above the hot stones. Water was then poured on these, until a dense steam arose. When Inmutanka thought that Will had stood it as long as he could, he withdrew him from the hot steam bath, although medicine men sometimes left their patients in too long, allowing them to be scalded to death.

In Will’s case it was cure, not kill. The fever quickly disappeared from his system and though it left him very weak he recovered so rapidly that in a few days he was as strong as ever, in fact, stronger, because all the impurities had been steamed out of his system, and the new blood generated was better than the old. He learned, too, from Inmutanka that he had won respect in the village by his courage and tenacity, and that many were in favor of lightening his labors, although the Fox was as stern as ever.

Will was still compelled to realize that he was a slave; that he, a white lad, the heir of untold centuries of civilization and culture, was the slave of a people who, despite all their courage and other virtues, were savages. They stood where, in many respects, his ancestors had stood ten or twenty thousand years ago. Again and again, the thought was so bitter that he felt like making a run for freedom and ending it all on the Indian spear. But the thought would change, and with it came the hope that some day or other the moment of escape would appear, and there was a lurking feeling, too, that his present life was not wholly unpleasant, or, at least, there were compensations.

An increased strength came with the rapid recovery from his illness. Beyond any question he had grown in both height and breadth since he had been in the mountains, and his muscles were as hard as iron. Not one of the Indian youths could exert as much direct strength as he, or endure as much.

His patience, which was now largely the result of calculation and will, began to have its visible effect upon the people. There is nothing that an Indian admires more than stoicism. The fortitude that can endure pain without a groan is to him the highest of attributes. Will had never complained, no matter how great his hardships or labors, and gradually they began to look upon him as one of their own. His face was tanned heavily by continuous exposure to all kinds of weather, his original garments were worn out, and he was now clad wholly in deerskins. A casual observer would have passed him at any time as a tall Indian youth.

One day as a mark of favor he was put back as a guard upon the herd of ponies, now considerably increased in numbers, probably by raids upon other tribes, and full of life, as they had done little all the autumn but crop the rich grass of the valley. Will found himself busy keeping them within bounds, but his old, happy touch soon returned, and the Indians, to their renewed amazement, soon saw the animals obeying him instinctively.

“It is magic,” said old Xingudan.

“Then it is good magic,” said Inmutanka, “and Wayaka is a good lad. He does not know it yet, but he is beginning to like our life. Think of that, O, Xingudan.”

“You were ever of soft heart, O, Inmutanka,” said Xingudan, as he turned away.

Will’s tasks were as long as ever, but they changed greatly in character. He was no longer compelled to work with the women and children, save when the tending of the herds brought him into contact with the boys, but there he was now an acknowledged chief. A distemper appeared among the ponies and the Sioux were greatly alarmed, but Will, with some simple remedies he had learned in the East, stopped it quickly and with the loss of but two or three ponies. Old Xingudan gave him no thanks save a brief, “It is well,” but the lad knew that he had done them a great service and that they were not wholly ungrateful.

He had proof of it a little later, when he was allowed to take part in the trapping and snaring of wild beasts, although he was always accompanied by three or four Indian youths, and was never permitted to have any weapon.

But he showed zeal, and he enjoyed the freedom, although it was only that of the valley and the slopes. He learned to set traps with the best of them, and became an adept in the taking and curing of game. All the while the autumn was deepening and wild life was becoming more endurable. The foliage on slopes and in the valley that had burned in fiery hues, now began to fade into yellow and brown. The winds out of the north grew fierce and cutting, and on the vast and distant peaks the snow line came down farther and farther.

“Waniyetu (winter) will soon be here,” said old Inmutanka.

“The village is in good condition to meet it,” said Will.

“Better than most villages of our people,” said Inmutanka. “The white man presses back the red man because the red man thinks only of today, while the white man thinks of tomorrow too. The white man is not any braver than the red man, often he is not as brave, and he is not as cunning, but when the Indian’s stomach is full his head goes to sleep. While the plains are covered with the buffalo in the summer, sometimes our people starve to death in the winter.”

“I suppose, doctor,” said Will, “that one can’t have everything. If he is anxious about the future he can’t enjoy the present.”

The old Sioux shook his head and remained dissatisfied.

“The buffalo is our life,” he said, “or, at least, the life of the Sioux tribes that ride the Great Plains. Manitou sends the buffalo to us. Buffaloes, in numbers past all human counting, are born by the will of Manitou under the ground and in the winter. When the spring winds begin to blow they come from beneath the earth through great caves and they begin their march northward. If the Sioux and the other Indian nations were to displease Manitou he might not send the buffalo herds out through the great caves, and then we should perish.”

Will afterward discovered that this was a common belief among the Indians of the plains. Some old men claimed to have seen these caves far down in Texas, and it was quite common for the ancients of the tribes to aver that their fathers or grandfathers had seen them. Most of them held, too, to the consoling belief that however great the slaughter of buffaloes by white man and red, Manitou would continue to send them in such vast numbers that the supply could never be exhausted, although a few such as Inmutanka had a fear to the contrary.

Inmutanka, as became his nature, was provident. The lodge that he and Will inhabited was well stored with pemmican, with nuts and a good store of shelled corn. It also held many dried herbs and to Will’s eyes, now long unused to civilization, it was a comfortable and cheerful place. A fire was nearly always kept burning in the centre, and he managed to improve the little vent and wind vane at the top in such a manner that the smoke was carried off well, and his eyes did not suffer from it.

Then a fierce, cold rain came, blown by bitter winds and stripping the last leaf from the trees. At Will’s own suggestion, vast brush shelters had been thrown up near the slopes. Crude and partial though they were, they gave the great pony herd much protection, and when old Xingudan inspected them carefully he looked at Will and said briefly: “It is good.”

Will felt that he had taken another step into favor, and it was soon proved by a lightening of his labors and an increase in his share of the general amusements. Life was continually growing more tolerable. The black periods were becoming shorter and the bright periods were growing longer. The evenings had now grown so cold that the young Sioux spent them mostly in the lodges, Will devoting a large part of his time to learning the language from Inmutanka, who was a willing teacher. As he had much leisure and the Sioux vocabulary was limited he could soon talk it fluently.

All the while the winter deepened and Will, seeing that he would have no possible chance of escape for many months, resigned himself to his captivity. The fierce rain that lasted two days, was followed by snow, but the Indians still hunted and brought in much game, particularly several fine elk of the great size found only in the far northwest. They stood as tall as a horse, and Will judged that they weighed more than a thousand pounds apiece.

Then deeper snow came and he could hear it thundering in avalanches on the distant slopes. He was quite sure now that they were even farther north than he had at first supposed, and that probably they would be snowed in all the winter in the valley, a condition to which the Indians were indifferent, as they had good shelter and plenty of food. They began to make snow-shoes, but Will judged that they would be used for hunting rather than for travel. There was no reason on earth that he knew why the village should move, or any of its people abandon it.

The warriors spent a part of their time making lances, bows, arrows and shields, sometimes working in a cave-like opening in the slope a little distance from the village. Will did his share of this work and grew exceedingly skilful. One very cold morning he and several others were toiling hard at the task under the critical eye of old Xingudan, who sat on a ledge wrapped in a pair of heavy blankets, Will’s fine repeating rifle lying across his knees.

Two of the warriors were sent back to the village for more materials, the others were dispatched on different tasks until finally only Will was left at work, with Xingudan watching. The Fox had seen many winters and summers, and his wilderness wisdom was great, but he was an Indian and a Sioux to the bone. He had noted the steady march of the white man toward the west, and even if the buffalo continued to come forever in countless numbers out of the vast caves in the south, they might come, in time, for the white man only and not for the red.

He regarded Will with a yellow and evil eye. Wayaka was a good lad he had proved it more than once but he was a representative of the conquering and hated race. Heraka had said that his fate, the most terrible that could be devised, must come some day, but Wayaka was not to know the hour of its coming; no sign that it was at hand must be given.

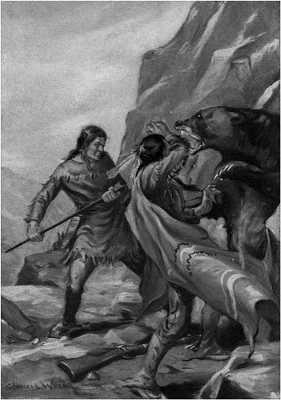

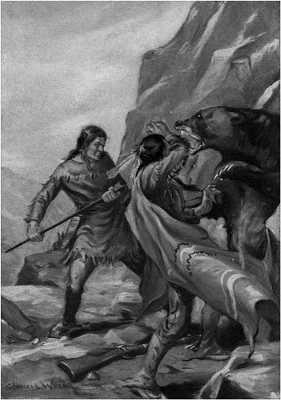

Xingudan went over again the words of Heraka, who was higher in rank than he, and he pursed his lips thoughtfully, trying to decide what he would do. Then he heard a woof and a snort, and a sudden lurch of a heavy body. He sprang to his feet in alarm. While he was thinking and inattentive, Rota (the grizzly bear), not yet gone into his winter sleep, vast and hungry, was upon him.

Xingudan was no coward, but he was not so agile as a younger man. He sprang to his feet and hastily leveling the repeating rifle fired once, twice. The Indian is not a good marksman, least of all when in great haste. One of the bullets flew wild, the other struck him in the shoulder, and to Rota that was merely the thrust of a needle, stinging but not dangerous. A stroke of a great paw and the rifle was dashed from the hands of the old chief. Then he upreared himself in his mighty and terrible height, one of the most powerful and ferocious beasts, when wounded, that the world has ever known.

Will had seen the rush of the grizzly and the defense of the chief. He snatched up a great spear, a weapon full ten feet long and with a point and blade as keen as a razor. He thrust it past Xingudan and, with all his might, full into the chest of the upreared bear. Strength and a prodigious effort driven on by nervous force sped the blow, and the bear, huge as he was, was fairly impaled. But Will still hung to the lance and continued to push.

Terrific roars of pain and anger came from the throat of the bear. A bloody foam gushed from his mouth and he fell heavily, wrenching the spear from the boy’s grasp and breaking the shaft as he fell. His great sides heaved, but presently he lay quite still, and Will, quivering from his immense nervous effort, knew that he was dead.

Old Xingudan, who had been half stunned, rose to his feet, steadied himself, and said with great dignity:

“You have saved my life, Wayaka. It was a great deed to slay Rota with only capa (a spear) and the beast, too, is one of the most monstrous that has ever come into this valley. You are no longer Wayaka, but you shall be known as Waditaka (The Brave), nor shall I forget to be grateful.” Will steadied himself and sat down on a rock, because he was somewhat dizzy after such a frightful encounter. But he was glad that it had occurred. He had no doubt that Xingudan had spoken with the utmost sincerity, and now the ruler of the village was his staunch friend.