The Phantom Foursome

I searched with great care through the short, wiry grass, and, in the manner of golfers on such occasions, used unbridled speech. I had followed the flight of the ball when I drove from the tee, noting the very slight pull—I generally drive a low, straight ball with a long carry—and, making due calculation for the little curve, I expected to walk at once to the spot where it lay.

But it was not there, nor anywhere within a radius of eight or ten yards. It was impossible that, with an eye trained by years on the links, I could miss it in such short grass, and under the circumstances I was warranted in drawing rather freely on the golfer’s vocabulary. It was a fine new ball, too. All balls of the same brand are just alike to the novice, but to the veteran there is a difference; now and then he finds one that has a fine springy feeling — one that makes a better response than usual to both wood and iron, and such was mine. I knew that I had a treasure, and I was not willing to give it up, especially when the drive was at least two hundred and ten yards, and if I did not find it I should lose the hole to Longworth, who takes a handicap of fourteen in our club, and who had never driven two hundred yards in his life.

“Why don’t you help me?” I exclaimed, with bitter sarcasm. “I hope you don’t think it very sporty to win the hole on the lost ball!”

Longworth was leaning on his driver, making no effort whatever to trace the ball, and my rather blunt attack was lost upon him, as they always are—Longworth is so even-tempered that he is scarcely human.

“I am not helping you,” he implied, quietly, “because I know it is useless. You will never find that ball.”

“All you know about it,” I said scornfully, widening my circle. “It’s bound to be here. I followed it, and I’m not going to give up, without a good hunt, the best ball that a club of mine has touched in a month.”

I continued the search, keeping my eyes on the grass and quoting an expressive jingle that always runs through my head on such occasions: “O! for an aut that would aut when it auto; And O! for a golf ball that would answer when I call!” But it was no good, the ball was hidden as completely as if the earth had swallowed it up.

I glanced up at Longworth, somewhat annoyed because he steadily refused to help me—we had no caddies. He was paying no attention to me at all, but was gazing at the massive stone ruins of the old fort and the silvery bosom of Lake Champlain beyond. I knew then that his mind was in the past. Longworth is a good deal of an amateur historian, and he had plenty of play for his fancy here on the Fort Ticonderoga golf-links, where the chapters of history cluster so thickly.

“I know that it has changed hands in war seven times,” I exclaimed, using bitter sarcasm again, “and that four nations have fought in it or about it—Indian, French, British, and American; but all that is of less importance than my lost golf-ball.”

“Drop it, Anderson,” said Longworth, quietly; “you’re wasting time. You’ll never find that golf-ball. Balls lost on the Fort Ticonderoga golf-links are never found. I know.”

I looked at him in surprise—he had spoken with emphasis. “Why not?” I asked. “There are no thieving caddies about. I haven’t seen a boy on the links.”

“It’s just as I tell you,” he replied; “let it go, like a good fellow, and we’ll move on to the next tee. I don’t want the hole; we’ll throw it out altogether.”

His manner was rather queer and it impressed me. I knew that Longworth would not speak in such a way without good cause, and, reluctantly abandoning that beautiful new golf-ball, I went on with him.

“Isn’t it grand?” he said, waving his hand in a wide circle.

I haven’t Longworth’s keen taste for the story of old times, but it all appealed to me too. Before us were the lonely stone walls that tell so much, and a herd of peaceful brown cows were grazing inside the ditch, probably right where Montcalm and Amherst and others had stood in times gone by, and had given directions to officers and men.

The links run between the fort itself and the earthworks where Montcalm inflicted such a heavy repulse on the English and Americans, and the golf-player has to follow directly in the path of armies and nations. In passing I had noticed these earthworks with interest. They stand just as they were thrown up a hundred and fifty years ago, save that they are now covered with bushes, and sometimes smart young trees grow from the crest.

We paused at the next tee and looked about us. I do not have the artistic temperament, but I felt the influence of the scene. The waters of Lake Champlain bore a faint tint of red in the late afternoon sun, and a slight mist was rising from them. To the eastward the Green Mountains, peak on peak and ridge on ridge, floated in a blue haze, and to the westward the vast maze of the Adirondacks loomed in silent grandeur through the same haze. Moreover, we were alone on the links, and neither of us had spoken in the last five minutes.

“That was your hole,” I said. I knew that I could beat him anyhow or I might not have been so generous about it.“You’ve got to take it. A lost ball is a lost ball, and one ought always to play by the rules, so it’s your honour.”

“Very well,” he said, and laying down his bag he teed up carefully.

This hole is about three hundred yards, and the fair green, leading down through a hollow, is quite narrow. But one hundred and twenty yards from the tee there is a little brook which one always ought to carry with his drive. I stood on one side, wondering whether Longworth would do it; he is none too sure with his drive, being addicted to the very amateurish vice of topping; but he caught the ball fairly—an accident, I suppose—and it whizzed when it left the wood. It was really a beautiful drive, straight and low, and after a flight of about a hundred yards seemed to rise for another flight, taking its second breath, as it were. Such shots as these do the soul good, and it is a chance one now and then that keeps duffers like Longworth in the game, season after season.

The ball landed in the middle of the fair green, had a long roll, and then lay still, perfectly visible, white and shining, from the tee. It was a full two hundred yards, and Longworth quietly stepped to one side, trying to hide his exultation. I knew that he might now make thirty bad drives in succession, but the memory of the good one would abide with him, and the others would be as if they had never been.

I drove, and my ball lay within a yard of Longworth’s. Then we walked deliberately down the hollow.

“It’s a sporty course,” I said, “and one can have scenery and history of the A No. 1 type thrown in free.”

“It’s unique,” he said.

We reached our balls, and, as I was away, I made a mashie pitch that landed well on the green, insuring me a four, with a possible three. Longworth took his midiron, not being expert enough for the mashie approach, and here I was sure that he would show his weakness. Any duffer can get off a screamer now and then, but it is only your true golfer who can make a succession of rattling good shots.

Just as I expected—I had noticed his bad stance—he sliced the approach, and the ball flew off to the side and into the rough, but did not penetrate it more than two yards.

“It’s your hole,” said Longworth, picking up his bag and thrusting the midiron into it.

“My hole?” I exclaimed, in stern reproof. “You’ll never be a golfer, Longworth, if you don’t show more courage than that. You might play out of the grass with a mashie or a niblick and the ball dead for the hole—one never knows what will happen. You’ve at least a chance for a half.”

“That might be true if it were not a lost ball.”

“Lost ball! Nonsense. I know exactly where it’s lying.”

“Didn’t I tell you that lost balls here are never found? And didn’t you have proof of it back there?” he replied, giving me that queer look of his again.

With that he put his bag over his shoulder and walked on toward the next tee. Well, it was his ball, and if he was willing to throw it away, and the hole too, it was not for me to object. I picked up my bag and followed him.

We were at the lowest point of the dip, and we seemed to be shut in by the lake and the two vast ranges of mountains, each in its blue haze. The mist on Lake Champlain was thickening, but the deep red of the setting sun burned through it, and the Northern twilight that lasts so long was at hand. But it was a fine time to play golf. There was no one to disturb us, no raucous shout of “Fore!” With a congenial partner one might now play his best game, and I steadied myself for an effort—the mental quality has a great deal to do with golf.

“Let’s make a record on the next hole,” I said to Longworth, and he nodded. He chose an unmarred ball from his bag and teed up.

“This must be something like the traditional Scotch mist,” he said, before he took his stance.

We had come out of the dip before reaching the tee, and I noticed now how grey the evening had turned. The surface of the lake was chill and ashen, and mists were rolling up the mountains. Everything about me, including the stone walls of the old fortress and Longworth himself, was taking on a grey, unsubstantial quality. Yet it was still admirable golf weather. One was not troubled by a glare, and it would be easy to follow the balls.

I drove, and lined it out straight and true for at least two hundred and thirty yards, the kind that delights the heart even of a scratch man—I am a scratch man in two clubs. Longworth followed with a topped ball that rolled about eighty yards, but well on the fair green. His cleek second, however, was a beauty, about one hundred and sixty yards and straight for the hole. I was giving him a stroke a hole, and I saw that I would have to look to it. As we walked on together toward my ball I calculated that with a brassy second lined out for all it was worth I might reach the green, and I took a swing or two with the club to loosen up my muscles—there had been no chance for brassy work before.

We had passed the turn and were on the homeward journey, this hole—a long one—being partly parallel with the one on which I had lost my first ball. As I took my position for the brassy shot, intending to send it two hundred yards, I happened to glance toward the tee from which I had driven the lost ball, and I was surprised to see a foursome come up for their drives.”

“Where did those fellows drop from?” I asked. “I thought we were alone on the links.”

Longworth made no reply, but I did not notice the fact at the moment.

“As we’ve got plenty of time I’ll wait until they drive,” I said. “We’re not far out of line with ’em, and it’s more than likely that at least one of the four will be wild.”

Longworth was still silent, and, dropping the head of my brassy to the ground, I waited. The four drove off with slowness and deliberation. Your practised golfer notices instinctively the style of every other golfer, and he can tell at once from his position and swing whether he is any good or not. These men, although at some distance, struck me as being rather stiff and angular, but I did not put them down as bad golfers; I credited them rather with an antique, or at least a strange, style.

All four made good drives, but the last was the best. Although a very long one, it was pulled a little and flew off toward us. I saw the ball strike on the short, close grass, bound along for twenty yards or so, and then lie white and fair right on the crest of a little ridge.

I play often on crowded links, and, while a real golfer always sticks to his own ball, the duffer, though quite innocently I will admit, sometimes plays another man’s; nor is it ever easy to convince him of his error. In order to protect myself from such novices, who roam wildly on every links, I always mark my ball with a little black cross at either pole, which is evidence that not even a woman player can dispute.

Now when the ball driven by the last man in the foursome stopped rolling and lay still on the hillock, focused in the most brilliant rays of the setting sun, I clearly saw that little black cross shining on the top of it. There, I knew, lay my lost ball.

“That’s my ball,” I said. “I’ll go over and claim it when the man comes up.”

Longworth put his hand upon my arm, and the hand felt cold through my sleeve.

“Don’t do it,” he said, earnestly. “Let him have it.”

“I think not,” I said, with irony; “and I thought you told me, Longworth, that balls lost on these links were never found?”

The pressure of his hand upon my arm increased, and he spoke again in words that were meant—if ever in his life Longworth meant anything he said.

“Anderson,” he exclaimed, “you are a friend of mine, and, to oblige me, promise me not to ask for that ball.”

“Oh, well,” I replied, “if you make a personal matter of it, I am glad to do as you ask.”

I looked at him in wonder. His face was perfectly white, but right in the middle of his forehead stood a large blue bead of perspiration. “Here is something outside of my knowledge,” I thought; and I was about to ask Longworth a question, but I reflected that there might be a personal difference between him and the foursome or some member of it, which would be no business of mine, and I refrained.

I made the brassy shot, a good one, as good as I had hoped, and we followed the ball. The foursome were coming from their tee, but their course now led somewhat away from us. The twilight or mist had increased perceptibly, but the golfer’s red coat of one of them gleamed through it. The same man wore on his head a sort of triangular red cap or hat rising to a peak. The last of the four was bare-headed. They walked briskly, but I did not hear any sound of footsteps, nor did any of the four speak.

“That’s a funny rig that fellow has on his head,” I said, meaning him of the red triangle.

“You know what fads golfers have,” replied Longworth, in a conciliatory tone.

We came up to Longworth’s ball and he took his midiron for his third shot. When he grasped the handle of the club I noticed that he trembled, and I said:

“Steady, old man; it’s no such terrible matter who wins the hole.”

He did not reply, but swung down at the ball and—missed it entirely! I was looking straight at the play, and I am confident that the head of the club passed not less than four inches above the ball. This was horrible, even for Longworth, and I could not account for it.”

“What ails you, old fellow?” I asked.

“I took my eye off the ball,” he replied, weakly; “I’ll do better next time.”

He kept his word—which in this case was not much to keep—and topped the ball about thirty yards farther on. In fact, Longworth went all to pieces—I never saw a more complete collapse on the links. On the next shot—his fifth—he dug up half a square yard of turf, topped his sixth, did the same for the seventh, which, however, reached the green, putted all the way across it, then back again, then to one side, making a most disgraceful exhibition of himself, and at last went down in twelve. I was down in five.

“If I were to get two figures on a bogie five hole,” I said, in freezing tones, “I think I should go back to the beginning of golf and start all over again.”

He took it with a little too much humility.

“I got rattled,” he said.

“So I saw,” I retorted. “Perhaps we had better hurry up a little. That foursome must have turned by this time, and they will be bearing down upon us in a minute.”

Both of us looked back, and found, as I had calculated, that the foursome had turned and were coming. Some quality in the air—it seemed to be the greyness—made them indistinct, but the four were obviously of different types. The man in the red coat and another in a suit that looked green appeared to be playing partners. These two were fair, but the other two were dark, one of them—the bare headed man—much darker than his partner, who was short and thick.

They came on steadily, every one of them using the short angular swing, but nearly always sending the ball straight and far. As well as I could tell at the distance, they never spoke.

“Come, Anderson,” exclaimed Longworth, hastily putting his cold hand on my arm, “we mustn’t let them overtake us.”

We went to the next tee, but here Longworth repeated his horrible exhibition, committing every fault that is possible in a golfer, topping, slicing, pulling, digging up turf, and showing a complete loss of nerve.

“I can’t play!” he exclaimed at last. “Let’s go home!”

“Not a bit of it,” I replied. “I’ve cautioned you before, Longworth, about yielding to a golfing weakness, and I’m not going to be an accessory to the crime. You’ve let yourself be rattled by that foursome which you think is pressing us, and I’m going to hold you to your work. But I’ll tell you what we’ll do. As we and the foursome are the only players on the links, we’ll cut across the green to the turn and drop in behind them. Then you won’t think they are pressing you.”

“It’s a good idea,” he said, in a tone of obvious relief, and we adopted it at once.

I was considerably annoyed. A good golfer hates to see the man with whom he is playing go to pieces; and, besides, the matter of the lost ball still rankled. One of these men, passing unnoticed across the green, must have picked it up when I was leaving the tee. If the ball had remained in the grass I certainly should have found it, and it was only deference for Longworth’s request that kept me from claiming it.

Our course led us back toward the lake, which was chillier and greyer than ever. The huge stone walls, silent and grim, looked down on its cold surface. The grazing cows were gone. The slopes of the mountains ended, half-way up, in mists. I had a lonesome feeling, and I was sorry that I had not agreed with Longworth to go home.”

“We are still on the old battlefield?” I said, looking up at the looming shadow of Mount Defiance.”

“It’s not one battlefield, but many,” said Longworth. “For fifty years four nations fought all over this place.”

In the twilight now I began to share Longworth’s vivid sense of old things, and so many of them heaped together here became an oppression to me. I had a feeling of unreality and my nerves became unsteady. I drove from the tee and made my worst top in two years, the ball rolling about twenty yards. Longworth did that most indefensible of all things on the links—he laughed at my misplay.”

“It seems that I have company,” he said.

I coldly ignored him, remaining silent until he made his drive, which was not much better than mine. Then we played our second shots. Mine was bad again, but I did not feel as much chagrin as before, because I was looking at the foursome, which was now directly ahead of us, playing, as usual, steadily and in silence.

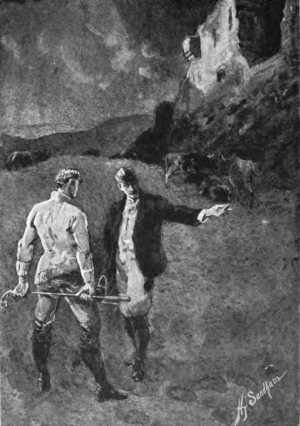

A red flame from the setting sun came through a gap in the mountains and fell full upon the four men. I saw them clearly for the first time. The red golfer’s coat of him who wore the triangular peaked hat was not a red golfer’s coat at all; but that of a soldier. I remembered the old pictures; the man in the red uniform was a British Grenadier and his partner in green was a New England Ranger. Of their antagonists, one in the white uniform with blue facings belonging to the ancient regiment La Sarre was unmistakably French, while his partner showed the swart, fierce features of a Huron.

I put my hand to my forehead, and when my fingers came away they were wet.

“You told me that four nations fought fifty years for this place?” I said to Longworth.

“Yes, four—Indian, French, English, and American.”

“So I know, so I should have known, anyhow,” I said, looking at the foursome swinging steadily on through the growing twilight.

“You understand now?” said Longworth, looking at me, white-faced.

“Yes, I understand. Longworth, I can never thank you enough for not letting me ask for that lost ball of mine.”

“Had it been necessary I should have used a club on you to keep you from doing it,” he said, grimly.

The sun sank lower, the red flame died, a sighing wind came up from the lake, and all round us the mountains were darkening fast. I looked at the shadowy walls of Fort Ticonderoga.

“Come, Longworth,” I said, “I think it’s time for us to go back to the village.”

He said nothing, but walked away swiftly with me. At the crest of the first ridge we stopped and looked back. Far ahead the phantom foursome played steadily on in the deepening twilight, and, satisfied with that one look, we stopped no more until we came to the village.