6 The Medicine Lodge

Okapa uttered a name. A young warrior, bare to the waist, stepped forward, entering the circular space within the ropes. He called a second name, and a second warrior responded in like manner, then a third and fourth, and so on until his list was complete with twelve. These were to be the dancers. One was chosen for every one hundred persons—men, women, and children—in the band. Therefore, this village had a population of twelve hundred.

The dancers, all young men, stood close together, awaiting the signal. They had been taking strange compounds, like drugs, that the Indians make from plants, and their eyes were shining with wild light. Their bodies already moved in short, convulsive jerks. Any dancer who did not respond to his name would have been disgraced for life.

After a few moments Okapa called six more names, with a short delay after every one. Six powerful warriors, fully armed with rifle, tomahawk, and knife, responded, and took their position beside the ropes, but outside the ring. They were the guard, and the guard was always half the number of the dancers.

Now the breathing of the multitude became more intense and heavy, like a great murmur, and Okapa handed to every one of the dancers a small whistle made of wood or bone, in the lower end of which was fastened a single tail feather of the chaparral cock or road runner, known to the Indians as the medicine bird. The dancers put the little whistles in their mouths, then the shaman arranged them in a circle facing the center. The crowd in the medicine lodge now pressed forward, uttering short gasps of excitement, but the guards kept them back from the ropes.

To the boy at the slit between the buffalo skins it was wild, unreal, and fantastic beyond degree, some strange, mysterious ceremony out of an old world that had passed. He saw the bare chests of the warriors rising and falling, the women as eager as the men, a great mass of light coppery faces, all intense and bent forward to see better. He knew that the air in the medicine lodge was heavy, and that its fumes were exciting, like those of gunpowder. Parallel with the dancers, and exactly in the center of their circle, hung the hideously carved and painted joss or wooden image. The twelve looked fixedly at it.

The shaman, standing on one side but within the circle, uttered a short, sharp cry. Instantly the twelve dancers began to blow shrilly and continuously upon their whistles, and they moved slowly in a circle around and around toward the right, their eyes always fixed upon the joss. The multitude broke into a wild chant, keeping time to the whistles, and around and around the dancers went. The shaman, stark naked, his whole body painted in symbols and hieroglyphics, never ceased to watch them. To Philip’s eyes he became at once the figure of Mephis-topheles.

It was difficult for Phil afterward to account for the influence this scene had over him. He was not within the medicine lodge. Where he lay outside the fresh cool air of the night blew over him. But he was unconscious of it. He saw only the savage phantasmagoria within, and by and by he began to have some touch of the feeling that animated the dancers and the crowd. An hour, two hours went by. Not one of the men had ceased for an instant to blow upon his whistle, nor to move slowly around and around the wooden image, always to the right. The dance, like the music, was monotonous, merely a sort of leaping motion, but no warrior staggered. He kept his even place in the living circle, and on and on they went. Perspiration appeared on their faces and gleamed on their naked bodies. Their eyes, wild and fanatical, showed souls steeped in superstition and the intoxication of the dance.

Many of those in the crowd shared in the fierce paroxysm of the hour, and pressed forward upon the ropes, as if to join the dancers, but the armed guard thrust them back. The dancers, their eyes fixed on the joss, continued, apparently intending to go around the circle forever. The air in the lodge, heavy with dust and the odors of oil and paint and human beings, would have been intolerable to one just coming from the outside, but it only excited those within all the more.

Phil’s muscles stiffened as he lay on the bough, but his position against one of the wooden scantlings that held the buffalo skins in place was easy, and he did not stir. His eyes were always at the slit and he became oppressed with a strange curiosity. How long could the men maintain the dancing and singing? He was conscious that quite a long time had passed, three or four hours, but there was yet no faltering. Nor did the chant of the crowd cease. Their song, as Phil learned later, ran something like this:

There were four or five verses of this, but as soon as they were all sung, the singers went back to the beginning and sang them again and again in endless repetition, while the twelve little whistles shrilled out their piercing accompaniment. The wind began to blow outside, but Phil did not feel it. Heavy clouds and vapors were drifting past, but he did not notice them, either. Would this incantation, for now it was nothing else, go on forever? Certainly the shaman, naked and hideously painted, presided with undiminished zest at this dance of the imps. He moved now and then about the circle of dancers, noting them sharply, his eye ready for any sign of wavering, whether of the spirit or the body.

Phil observed presently some shifting in the crowd of spectators, and then a new face appeared in the copper-colored mass. It was the face of a white man, and with a little start the boy recognized it as that of Bill Breakstone. It may seem singular, but he felt a certain joy at seeing him there. He had felt sure all the while that Breakstone was a prisoner, and now he had found him. Certainly he was in the midst of enemies. Nevertheless, the boy had gone a step forward in his search.

Breakstone was not bound—there was no need of it, a single white man in such a crowd—and Phil thought he could see pallor showing through his tan, but the captive bore himself bravely. Evidently he was brought forward as a trophy, as the chant was broken for a moment or two, and a great shout went up when he approached, except from the dancers, who circled on and on, blowing their whistles, without ceasing. Okapa walked over to Breakstone and brandished a tomahawk before his face, making the sharp blade whistle in front of his nose and then beside either cheek. Phil held his breath, but Bill Breakstone folded his arms and stood immovable, looking the ferocious shaman squarely in the face. It was at once the best thing and the hardest thing to do, never to flinch while a razor edge of steel flashed so close to one’s face that it felt cold as it passed.

Two or three minutes of such amusement satisfied the shaman, and, going back inside the ropes, he turned his attention again to the dancers. It was now much past midnight, and the slenderest and youngest of the warriors was beginning to show some signs of weakness. The shaman watched him keenly. He would last a long time yet, and if he gave up it would not occur until he fell unconscious. Then he would be dragged out, water would be thrown over him, and, when he recovered, he would be compelled to resume dancing if the shaman ordered it. Sometimes the dancers died of exhaustion. It was well to be in the good graces of the shaman.

But Phil was now watching Bill Breakstone, who was pressing back in the crowd, getting as far as possible from the ropes that enclosed the dancers. Once or twice he saw Breakstone’s face, and it seemed to him that he read there an intention, a summoning of his faculties and resolution for some great attempt. The mind of a man at such a time could hold only one purpose, and that would be the desire to escape. Yet he could not escape single-handed, despite the absorption of the Comanches in the medicine dance. There was only one door to the great lodge, and it was guarded. But Phil was there. He felt that the hand of Providence itself had sent him at this critical moment, and that Bill Breakstone, with his help, might escape.

He watched for a long time. It must have been three or four o’clock in the morning. The whistling, shrill, penetrating, now and then getting horribly upon his nerves, still went on. The wavering warrior seemed to have got his second wind, and around and around the warriors went, their eyes fixed steadily upon the hideous wooden face of the joss. Phil believed that it must be alive to them now. It was alive to him even with its ghastly cheek of black and its ghastly cheek of white, and its thick, red lips, grinning down at the fearful strain that was put upon men for its sake.

Phil’s eyes again sought Breakstone. The captive had now pushed himself back against the buffalo skin wall and stood there, as if he had reached the end of his effort. He, too, was now watching the dancers. Phil noted his position, with his shoulder against one of the wooden pieces that supported the buffalo hide, and the lad now saw the way. Courage, resolution, and endurance had brought him to the second step on the stairway of success.

Phil sat on the bough and stretched his limbs again and again to bring back the circulation. Then he became conscious of something that he had not noticed before in his absorption. It was raining lightly. Drops fell from the boughs and leaves, but his rifle, sheltered against his coat, was dry, and the rain might serve the useful purpose of hiding the traces of footsteps from trailers so skilled as the Comanches.

He dropped to the ground and moved softly by the side of the lodge, which was circular in shape, until he came to the point at which he believed Bill Breakstone rested. There was the wooden scantling, and, unless he had made a great mistake, the shoulder of the captive was pressed against the buffalo hide on the left of it. He deliberated a moment or two, but he knew that he must take a risk, a big risk. No success was possible without it, and he drew forth his hunting-knife. Phil was proud of this hunting-knife. It was long, and large of blade, and keen of edge. He carried it in a leather scabbard, and he had used it but little. He put the sharp point against the buffalo hide at a place about the height of a man, and next to the scantling on the left. Then he pressed upon the blade, and endeavored to cut through the skin. It was no easy task. Buffalo hide is heavy and tough, but he gradually made a small slit, without noise, and then, resting his hand and arm, looked through it.

Phil saw little definite, only a confused mass of heads and bodies, the light of torches gleaming beyond them, and close by, almost against his eyes, a thatch of hair. That hair was brown and curling slightly, such hair as never grew on the head of an Indian. It could clothe the head of Bill Breakstone and none other. Phil’s heart throbbed once more. Courage and decision had won again. He put his mouth to the slit and whispered softly:

“Bill! Bill! Don’t move! It is I, Phil Bedford!”

The thatch of brown hair, curling slightly at the ends, turned gently, and back came the whisper, so soft that it could not have been heard more than a foot away:

“Phil, good old Phil! You’ve come for me! I might have known it!”

“Are they still looking at the dance?”

“Yes, they can’t keep their eyes off it.”

“Then now is your only chance. You must get out of this medicine lodge, and I will help you. I’m going to cut through the buffalo hide low down, then you must stoop and push your way out at the slash, when they’re not looking.”

“All right.” said Bill Breakstone, and Phil detected the thrill of joy in his tone. Phil stooped and bearing hard upon the knife, cut a slash through the hide from the height of his waist to the ground.

“Now, Bill,” he whispered, “when you think the time has come, press through.”

“All right.” again came the answer with that leaping tone in it.

Phil put the knife back in its scabbard, and, pressing closely against the hide beside the slash, waited. Bill did not come. A minute, another, and a third passed. He heard the monotonous whistling, the steady chant, and the ceaseless beat of the dancer’s feet, but Breakstone made no sound. Once more he pressed his lips to the slit, and said in the softest of tones:

“Are you coming, Bill?”

No answer, and again he waited interminable minutes. Then the lips of the buffalo skin parted, and a shoulder appeared at the opening. It was thrust farther, and a head and face, the head and face of Bill Breakstone, followed. Then he slipped entirely out, and the tough buffalo hide closed up behind him. Phil seized his hand, and the two palms closed in a strong grasp.

“I had to wait until nobody was looking my way.” whispered Breakstone, “and then it was necessary to make it a kind of sleight-of-hand performance. I slipped through so quick that any one looking could only see the place where I had been.”

Then he added in tones of irrepressible admiration:

“It was well done, it was nobly done, it was grandly done, Sir Philip of the Night and the Knife.”

“Hark to that!” said Phil, “they miss you already!”

A shout, sharp, shrill, wholly different from all the other sounds, came from within the great medicine lodge. It was the signal of alarm. It was not repeated, and the whistling and wailing went on, but Phil and Breakstone knew that warriors would be out in an instant, seeking the lost captive.

“We must run for it.” whispered Breakstone, as they stood among the trees.

“It’s too late,” said Phil. Warriors with torches had already appeared at either end of the grove, but the light did not yet reach where the two stood in the thick darkness, with the gentle rain sifting through the leaves upon them. Phil saw no chance to escape, because the light of the torches reached into the river bed, and then, like lightning, the idea came to him.

“Look over your head, Bill.” he said. “You stand under an Indian platform for the dead, and I under another! Jump up on yours and lie down between the mummies, and I’ll do the same here. Take this pistol for the last crisis, if it should come!”

He thrust his pistol into his companion’s hand, seized a bough, and drew himself up. Bill Breakstone was quick of comprehension, and in an instant he did likewise. Two bodies tightly wrapped in deerskin were about three feet apart, and Phil, not without a shudder, lay down between them. Bill Breakstone on his platform did the same. They were completely hidden, but the soft rain seeped through the trees and fell upon their faces. Phil stretched his rifle by his side and scarcely breathed.

The medicine dance continued unbroken inside. Okapa, greatest shaman of the Comanches, still stood in the ring watching the circling twelve. The symbols and hieroglyphics painted on his naked body gleamed ruddily in the light of the torches, but the war chief, Black Panther, and the other great war chief, Santana, had gone forth with many good warriors. The single cry had warned them. Sharp eyes had quickly detected the slit in the wall of buffalo skin, and even the littlest Indian boy knew that this was the door by which the captive had passed. He knew, too, that he must have had a confederate who had helped from the outside, but the warriors were sure that they could yet retake the captive and his friend also.

Black Panther, Santana, and a dozen warriors, some carrying torches, rushed into the grove. They ran by the side of the medicine lodge until they came to the slit. There they stopped and examined it, pulling it open widely. They noticed the powerful slash of the knife that had cut through the tough buffalo hide four feet to the ground. Then they knelt down and examined the ground for traces of footsteps. But the rain, the beneficent, intervening rain, had done its work. It had pushed down the grass with gentle insistence and flooded the ground until nothing was left from which the keenest Comanche could derive a clue. They ran about like dogs in the brake, seeking the scent, but they found nothing. Warriors from the river had reported, also, that they saw nobody.

It was marvelous, incomprehensible, this sudden vanishing of the captive and his friend, and the two chiefs were troubled. They glanced up at the dark platforms of the dead and shivered a little. Perhaps the spirits of those who had passed were not favorable to them. It was well that Okapa made medicine within to avert disaster from the tribe. But Black Panther and Santana were brave men, else they would not have been great chiefs, and they still searched in this grove, which was more or less sacred, examining behind every tree, prowling among the bushes, and searching the grass again and again for footsteps.

Phil lay flat upon his back, and those moments were as vivid in his memory years afterward as if they were passing again. Either elbow almost touched the shrouded form of some warrior who had lived intensely in his time. They did not inspire any terror in him now. His enemies alive, they had become, through no will of their own, his protectors dead. He did not dare even to turn on his side for fear of making a noise that might be heard by the keen watchers below. He merely looked up at the heavens, which were somber, full of drifting clouds, and without stars or moon. The rain was gradually soaking through his clothing, and now and then drops struck him in the eyes, but he did not notice them.

He heard the Comanches walking about beneath him, and the guttural notes of their words that he did not understand, but he knew that neither he nor Bill Breakstone could expect much mercy if they were found. After one escape they would be lucky if they met quick death and not torture at the hands of the Comanches. He saw now and then the reflection of the torch-lights high up on the walls of the medicine lodge, but generally he saw only the clouds and vapors above him.

Despite the voices and footsteps, Phil felt that they would not be seen. No one would ever think of looking in such places for him and Breakstone. But the wait was terribly long, and the suspense was an acute physical strain. He felt his breath growing shorter, and the strength seemed to depart from his arms and legs. He was glad that he was lying down, as it would have been hard to stand upon one’s feet and wait, helpless and in silence, while one’s fate was being decided. There was even a fear lest his breathing should turn to a gasp, and be heard by those ruthless searchers, the Comanches. Then he fell to calculating how long it would be until dawn. The night could not last more than two or three hours longer, and if they were compelled to remain there until day, the chance of being seen by the Comanches would become tenfold greater.

He longed, also, to see or hear his comrade who lay not ten feet away, but he dared not try the lowest of whispers. If he turned a little on his side to see, the mummy of some famous Comanche would shut out the view; so he remained perfectly still, which was the wisest thing to do, and waited through interminable time. The rain still dripped through the foliage, and by and by the wind rose, the rain increasing with it. The wet leaves matted together, but above wind and rain came the sound from the medicine lodge, that ceaseless whistling and beating of the dancers’ feet. He wondered when it would stop. He did not know that Comanche warriors had been known to go around and around in their dance three days and three nights, without stopping for a moment, and without food or water.

After a long silence without, he heard the Comanches moving again through the grove, and the reflection from the flare of a torch struck high on the wall of the medicine lodge. They had come back for a second search! He felt for a few moments a great apprehension lest they invade the platforms themselves, but this thought was quickly succeeded by confidence in the invisibility of Breakstone and himself, and the superstition of the Indians.

The tread of the Comanches and their occasional talk died away, the lights disappeared from the creek bed, and the regions, outside the medicine lodge and the other lodges, were left to the darkness and the rain. Phil felt deep satisfaction, but he yet remained motionless and silent. He longed to call to Breakstone, but he dreaded lest he might do something rash. Bill Breakstone was older than he, and had spent many years in the wilderness. It was for him to act first. Phil, despite an overwhelming desire to move and to speak, held himself rigid and voiceless. In a half hour came the soft, whispering question:

“Phil, are you there?”

It was Breakstone from the next tree, and never was sound more welcome. He raised himself a little, and drops of rain fell from his face.

“Yes, I’m here, Bill, but I’m mighty anxious to move.” he replied in the same low tone.

“I’m tired of having my home in a graveyard, too,” said Bill Breakstone, “though I’ll own that for the time and circumstances it was about the best home that could be found this wide world over. It won’t be more than an hour till day, Phil, and if we make the break at all we must make it now.”

“I’m with you,” said Phil. “The sooner we start, the better it will please me.”

“Better stretch yourself first about twenty times.” said Bill Breakstone. “Lying so long in one position with the rain coming down on top of you may stiffen you up quite a lot.”

Phil obeyed, flexing himself thoroughly. He sat up and gently touched the mummy on either side of him. He had no awe, no fear of these dead warriors. They had served him well. Then, swinging from a bough, he dropped lightly to the ground, and he heard the soft noise of some one alighting near him. The form of Bill Breakstone showed duskily.

“Back from the tombs,” came the cheerful whisper. “Phil, you’re the greatest boy that ever was, and you’ve done a job that the oldest and boldest scout might envy.

“I composed that rhyme while I was lying on the death platform up there. I certainly had plenty of time—and now which way did you come, Phil?”

“Under the shelter of the creek bank. The woods run down to it, and it is high enough to hide a man.”

“Then that is the way we will go, and we will not linger in the going. Let the Comanches sing and dance if they will. They can enjoy themselves that way, but we can enjoy ourselves more by running down the dark bed of a creek.”

They slipped among the wet trees and bushes, and silently lowered themselves down the bank into the sand of the creek bottom. There they took a parting look at the medicine lodge. It showed through a rift in the trees, huge and dark, and on either side of it the two saw faint lights in the village. Above the soft swishing of the rain rose the steady whistling sound from the lodge, which had never been broken for a moment, not even by the escape of the prisoner and the search.

“I was never before so glad to tell a place good-by.” whispered Bill Breakstone.

“It’s time to go,” said Phil. “I’ll lead the way, as I’ve been over it once.”

He walked swiftly along the sand, keeping well under cover of the bank, and Bill Breakstone was close behind him. They heard the rain pattering on the surface of the water, and both were wet through and through, but joy thrilled in every vein of the two. Bill Breakstone had escaped death and torture; Phil Bedford, a boy, had rescued him in face of the impossible, and they certainly had full cause for rejoicing.

“How far down the creek bed do you think we ought to go?” asked Breakstone.

“A quarter of a mile anyway,” replied Phil, “and then we can cut across the plain and enter the forest.”

Everything had been so distinct and vivid that he remembered the very place at which he had dropped down into the creek bed, when he approached the medicine lodge, and when he came to it again, he said: “Here we are,” springing up at one bound. Breakstone promptly followed him. Then a figure appeared in the dusk immediately in front of Phil, the figure of a tall man, naked save the breech cloth, a great crown of brightly colored feathers upon his head. It was a Comanche warrior, probably the last of those returning from the fruitless search for the captive.

The Comanche uttered the whoop of alarm, and Phil, acting solely on impulse, struck madly with the butt of his rifle. But he struck true. The fierce cry was suddenly cut short. The boy, with a shuddering effect, felt something crush beneath his rifle stock. Then he and Bill Breakstone leaped over the fallen body and ran with all their might across the plain toward the woods.

“It was well that you hit so quick and hard.” breathed Breakstone, “but his single yell has alarmed the warriors. Look back, they are getting ready to pursue.”

Phil cast one hurried glance over his shoulder. He saw lights twinkling among the Comanche lodges, and then he heard a long, deep, full-throated cry, uttered by perhaps a hundred throats.

“Hark to them!” exclaimed Breakstone. “They know the direction from which that cry came, and you and I, Phil, will have to make tracks faster than we ever did before in our lives.”

“At any rate, we’ve got a good start,” said Phil.

They ran with all speed toward the woods, but behind them and in other directions they heard presently the beat of hoofs, and both felt a thrill of alarm.

“They are on their ponies, and they are galloping all over the plain,” said Bill Breakstone. “Some of them are bound to find us, but you’ve the rifle, and I’ve the pistol!”

They ran with all their might, but from two or three points the ominous beat of hoofs came closer. They were devoutly glad now of the rain and the shadowed moon that hid them from all eyes except those very near. Both Phil and Breakstone stumbled at intervals, but they would recover quickly, and continue at undiminished speed for the woods, which were now showing in a blacker line against the black sky.

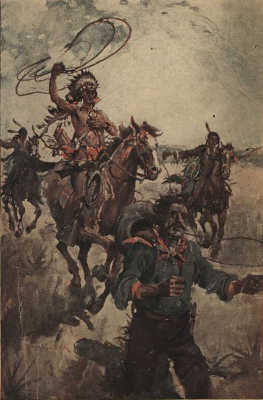

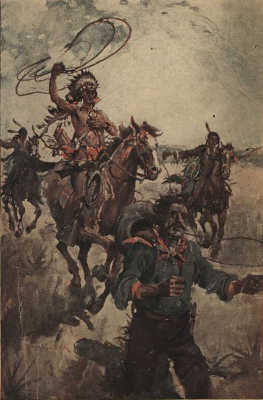

There was a sudden swift beat of hoofs, and two warriors galloped almost upon them. Both the warriors uttered shouts at sight of the fugitives, and fired. But in the darkness and hurry they missed. Breakstone fired in return, and one of the Indians fell from his pony. Phil was about to fire at the other, but the Comanche made his pony circle so rapidly that in the faint light he could not get any kind of aim. Then he saw something dark shoot out from the warrior’s hand and uncoil in the air. A black, snakelike loop fell over Bill Breakstone’s head, settled down on his shoulders, and was suddenly drawn taut, as the mustang settled back on his haunches. Bill Breakstone, caught in the lasso, was thrown to the ground by the violent jerk, but with the stopping of the horse came Phil’s chance. He fired promptly, and the Comanche fell from the saddle. The frightened mustang ran away, just as Breakstone staggered dizzily to his feet. Phil seized him by the arm.

“Come, Bill, come!” he cried. “The woods are not thirty yards away!”

“Once more unto the breach, or rather the woods!” exclaimed the half-unconscious man. “Lead on, Prince Hal, and I follow! That’s mixed, but I mean well!”

They ran for the protecting woods, Breakstone half supported by Phil, and behind them they now heard many cries and the tread of many hoofs. A long, black, snake-like object followed Bill Breakstone, trailing through the grass and weeds. They had gone half way before Phil noticed it. Then he snatched out his knife and severed the lasso. It fell quivering, as if it were a live thing, and lay in a wavy line across the grass. But the fugitives were now at the edge of the woods, and Bill Breakstone’s senses came back to him in full.

“Well done again, Sir Philip of the Knife and the Ready Mind,” he whispered. “I now owe two lives to you. I suppose that if I were a cat I would in the end owe you nine. But suppose we turn off here at an angle to the right, and then farther on we’ll take another angle. I think we’re saved. They can’t follow us on horses in these dense woods, and in all this darkness.”

They stepped lightly now, but drew their breaths in deep gasps, their hearts throbbing painfully, and the blood pounding in their ears. But they thanked God again for the clouds and the moonless, starless sky. It could not be long until day, but it would be long enough to save them.

They went nearly a quarter of a mile to the right, and then they took another angle, all the while bearing deeper into the hills. From time to time they heard the war cries of the Comanches coming from different points, evidently signals to one another, but there was no sound of footsteps near them.

“Let’s stop and rest a little,” said Bill Breakstone. “These woods are so thick and there is so much undergrowth that they cannot penetrate here with horses, and, as they know that at least one of us is armed, they will be a little wary about coming here on foot. They know we’d fight like tigers to save ourselves. ‘Thrice armed is he who hath his quarrel just,’ and if a man who is trying to save his life hasn’t got a just quarrel, I don’t know who has. Here’s a good place.”

They had come to a great oak which grew by the side of a rock projecting from a hill. The rain had been gentle, and the little alcove, formed by the rock above and the great trunk of the tree on one side, was sheltered and dry. Moreover, it contained many dead leaves of the preceding autumn, which had been caught there when whirled before the winds. It was large enough for two, and they crept into it, not uttering but feeling deep thanks.