17 The Thread, the Key, and the Dagger

When John Bedford rose the next morning he was several years younger. He held himself erect, as became his youth, a little color had crept into the pallid face, and his heart was still full of hope. He had seen the light that Catarina had promised. Surely the world was making a great change for him, and he reasoned again that, his present state being so low, any possible change must be for the better.

But the day passed and nothing happened. Diego, the slouching soldier, brought him his food, and, bearing in mind the vague words of Catarina, he noticed it carefully while he ate. There was nothing unusual. It was the same at his supper. The rosy cloud in which his hopes swam faded somewhat, but he was still hopeful. No light had been promised for the second night, but he watched for long hours, nevertheless, and he could not restrain a sense of disappointment when he turned away.

A second day passed without event, and a third, and then a fourth. John Bedford was overcome by a terrible depression. Catarina was old and foolish, or perhaps she, too, had shown at last the cunning and trickery that he began to ascribe to all these people. He would stay in that cell all his life, fairly buried alive. A fierce, unreasoning anger took hold of him. He would have flared out at stolid Diego who brought the food, but he did not want those heavy chains put back on his ankles. His head was now healed enough for the removal of the bandage, but a red streak would remain for some time under the hair. Doubtless the hair had saved him from a fracture of the skull. Every time he put his hand to the wound, which was often, his anger against de Armijo rose. It was that cold, silent anger which is the most terrible and lasting of all.

Although he was back in the depths, John felt that the brief spell of hope had been of help to him. His wound had healed more rapidly, and he was sure that he was physically stronger. Yet the black depression remained. It was even painful for him to look through the slit at his piece of the slope, which he sometimes called his mountain garden. He avoided it, as a place of hope that had failed. On the sixth day, Diego brought him his dinner a little after the dinner hour. He was sitting on the edge of his cot and he bit into a tamale. His teeth encountered something tough and fibrous, and he was about to throw it down in disgust. Then the words of Catarina, those words which he had begun to despise, came suddenly back to him. He put the tamale down and began to eat a tortilla, keeping his eye on Diego, who slouched by the wall in the attitude of a Mexican of the lower classes, that lazy, dreaming attitude that they can maintain, for hours.

Presently Diego glanced at the loophole, and in an instant John whipped the tamale off the plate and thrust it under the cover of the cot. Then he went on calmly with his eating, and drank the usual amount of bad coffee. Diego, who had noticed nothing, took the empty tray and went out, carefully locking the heavy door behind him. Then John Bedford did something that showed his wonderful power of self-restraint. He did not rush to the bed, eager to read what the tamale might contain, but strolled to the loophole and looked out for at least a quarter of an hour. He did not wish any trick to be played upon him by a sudden return of Diego. Yet he was quivering in every nerve with impatience.

When he felt that he was safe, he returned to the cot and took out the tamale. He carefully pulled it open, and in the middle he found the tough, fibrous substance that his teeth had met. He had half expected a paper of some kind, rolled closely together, that the writing might not perish, and what he really did find caused a disappointment so keen that he uttered a low cry of pain.

He held it up in his hand. It was nothing more than a small package of thread, such as might have been put in a thimble. What could it mean? Of what possible use was a coil of fifty yards or so of thread that would not sustain the weight of half a pound? Was he to escape through the loophole on that as a rope? He looked at the loophole four inches broad, and then at the tiny thread, and it seemed to him such a pitiful joke that he sat down on the cot and laughed, not at the joke itself, but at any one who was foolish enough to perpetrate such a thing.

He tested the thread. It was stronger than he had thought. Then he put it on his knee, took his head in his two hands, and sat staring at the thread for a long time, concentrating his thoughts and trying to evolve something from this riddle. It did mean something. No one would go to so much trouble to play a miserable joke on a helpless captive like himself. Catarina certainly would not do it, and she had given him the hint about the food, a hint that had come true. He kept his mind upon the one point so steadily and with so much force that his brain grew hot, and the wound, so nearly cured, began to ache again. Yet he kept at it, studying out every possible twist and turn of the riddle. At last he tested the thread again. It was undeniably strong, and then he looked at the loophole. Only one guess savored of possibility. He must hang the thread out of the loophole.

He ate the rest of the tamale, hid the little package under his clothing, and at night, after supper, when the darkness was heavy, he threw the end of the thread through the long slot, a cast in which he did not succeed until about the twelfth attempt. Then he let the thread drop down. He knew about how many feet it was to the pavement below, and he let out enough with three or four yards for good count. Then he found that he had several yards left, which he tied around one of the iron bars at the edge of the loophole. It was a black thread, and, although some one might see it by daylight, there was not one chance in a thousand that any one would see it at night.

“Fishing,” he said to himself, as he lay down on his cot, intending to sleep awhile, but to draw in the thread before the day came. It might be an idle guess, he could not even know that the thread was not clinging to the stone wall, instead of reaching the ground, but there was relief in action, in trying something. He fell asleep finally, and when he awoke he sprang in an instant to the floor. The fear came with his waking senses that he might have slept too long, and that it was broad daylight. The fear was false. It was still night, with only the moon shining at the loophole. But he judged that most of the night had passed, and his impatience told him that if anything was going to happen it had happened already. He went to the window. His thread was there, tied to the bar and, like a fisherman, he began to pull it in. He felt this simile himself. “Drawing in the line.” he murmured. “Now I wonder if I have got a bite.”

Although he spoke lightly to himself, as if a calm man would soothe an excitable one, he felt the cold chill that runs down one’s spine in moments of intense excitement. The moonlight was good, and he watched the black thread come in, inch by inch, while the hand that drew it trembled. But he soon saw that there was no weight at the other end, and down his heart went again into the blackest depths of black despair. Nevertheless, he continued to pull on the thread, and, as it emerged from the darkness into the far end of the loophole, he thought he saw something tied on the end, although he was not sure, it looked so small and dim. Here he paused and leaned against the wall, because he suddenly felt weak in both mind and body. These alternations between hope and despair were shattering to one who had been confined so long between four walls. The very strength of his desire for it might make him see something at the end of the thread when nothing was really there.

He recovered himself and pulled in the thread, and now hope surged up in a full tide. Something was on the end of the thread. It was a little piece of paper not more than an inch long, rolled closely and tied tightly around the center with the thread. He drew up his stool and sat down on it by the loophole, where the moonlight fell. Then he carefully picked loose the knot and unrolled the paper. The light was good enough, and he read these amazing words:

“You seem to be a brave fellow like your brother; then now is the time to show your courage, and remember, also, that I can do all the talking for both of us. Talking is my great specialty.”

John leaned against the wall. His surprise and joy were so great that he was overpowered. He realized now that his hope had merely been a forlorn one, an effort of the will against spontaneous despair. And yet the miracle had been wrought. His letter, in some mysterious manner, had got through to Phil, and Phil had come. He must have friends, too, because the letter had not been written by Phil. It was in a strange handwriting. But this could be no joke of fate. It was too powerful, too convincing Everything fitted too well together. It must have started somehow with Catarina, because all her presages had come true. She was the cook, she had put the thread in the tamale. How had the others reached her?

But it was true. His letter had gone through, and the brave young boy whom he had left behind had come. He was somewhere about the Castle of Montevideo, and since such wonders had been achieved already, others could be done. From that moment John Bedford never despaired. After reading the letter many times, he tore it into minute fragments, and, lest they should be seen below and create suspicion, he ate them all and with a good appetite. Then he rolled up the thread, put it next to his body, and, for the first time in many nights, slept so soundly that he did not awake until Diego brought him his breakfast. Then he ate with a remarkable appetite, and after Diego had gone he began to walk up and down the cell with vigorous steps. He also did many other things which an observer, had one been possible, would have thought strange.

John not only walked back and forth in his cell, but he went through as many exercises as his lack of gymnastic equipment permitted, and he continued his work at least an hour. He wished to get back his strength as much as possible for some great test that he felt sure was coming. If he were to escape with the help of Phil and unknown others, he must be strong and active. A weakling would have a poor chance, no matter how numerous his friends. He had maintained this form of exercise for a long period after his imprisonment, but lately he had become so much depressed that he had discontinued it.

He felt so good that he chaffed Diego when he came back with his food at dinner and supper. Diego had long been a source of wonder to John. It was evident that he breathed and walked, because John had seen him do both, and he could speak, because at rare intervals John had heard him utter a word or two, but this power of speech seemed to be merely spasmodic. Now, while John bantered him, he was as stolid as any wooden image of Aztecs or Toltecs, although John spoke in Spanish,, which, bad as it was Diego could understand.

He devoted the last hours of the afternoon to watching his distant garden. It had always been a pleasant landscape to him, but now it was friendlier than ever. That was a fine cactus, and it was a noble forest of dwarf pine or cedar—he wished he did know which. An hour after the dark had fully come he let the thread out again.

“This beats any other fishing I ever did,” he murmured. “Well, it ought to. It’s fishing for one’s life.”

He was calmer than on the night before, and fell asleep earlier, but he had fixed his mind so resolutely on a waking time at least an hour before daylight that he awoke almost at the appointed minute. Then he tiptoed across the cold floor to the thread. Nobody could have heard him through those solid walls, but the desire for secrecy was so strong that he unconsciously tiptoed, nevertheless. He pulled the thread, and he felt at once that something heavy had been fastened to the other end. Then he pulled more slowly. The thread was very slender, and the weight seemed great for so slight a line. If it were to break, the tragedy would be genuinely terrible. He had heard of the sword suspended by a single hair, and it seemed to him that he was in some such case. But the thread was stronger than John realized—it had been chosen so on purpose—and it did not break.

As the far end of the thread approached the loophole, he was conscious of a slight metallic ring against the stone wall. His interest grew in intensity. Phil and these unknown friends of his were sending him something more than a note. He pulled with exceeding slowness and care now, lest the metallic object hook against the far edge of the loophole. But it came in safely, slid across the stone, and reached his hand. It was a large iron key, with a small piece of paper tied around it. He tore off the paper, and read, in a handwriting the same as that on the first one:

“This is the key to your cell, No. 37, but do not use it. Do not even put it in the lock until the fourth night from to-night. Then at midnight, as nearly as you can judge, unlock and go out. Let out the thread for the last time to-morrow night.”

John looked at the key and glanced longingly at the lock. He had no doubt that it would fit. But he obeyed orders and did not try it. Instead he thrust it into the old ragged mattress of his cot. He resumed his physical exercises the next day, giving an hour to them in the morning and another hour in the afternoon. They helped, but the breath of hope was doing more for him, both mind and body, than anything else. He felt so strong and active that he did not chaff Diego any more lest the Mexican, stolid and wooden though he was, might suspect something.

He let out the thread according to orders, and, at the usual time, drew in a dagger, slender and very light, but long and keen as a razor. He read readily the purpose of this. There would be much danger when he opened the door to go out, and he must have a weapon. He ran his finger along the keen edge and saw that it would be truly formidable at close quarters. Then he hid it in his mattress with the key, wound up the thread, and put it in the same place. All had now come to pass as promised, and he felt that the remainder would depend greatly upon himself. So he settled down as best he could to three days and nights of almost intolerable waiting. Dull and heavy as the time was, and surely every second was a minute, many fears also came with it. They might take it into their heads to change that ragged old mattress of his, and then the knife, the thread, and the key would be found. He would dismiss such apprehensions with the power of reason, but the power of fear would bring them back again. Too much now depended upon his freedom from examination and search to allow of a calm mind.

Yet time passed, no matter how slow, and he was helped greatly by his physical exercises, which gave him occupation, besides preparing him for an expected ordeal. Hope, too, was doing its great work. He could fairly feel the strength flowing back into his veins, and his nerves becoming tougher and more supple. Every night he looked out at the mountain slope and itemized his little garden there that he had never touched, shrub by shrub, stone by stone, not forgetting the great cactus. He told himself that he did not expect to see any light there again, because the unknown sender of messages had not spoken of another, but, deep down at the bottom of his heart, he was hoping to behold the torch once more, and he felt disappointment when it did not appear.

He tried to imagine how Phil looked. He knew that he must be a great, strong boy, as big as a man. He knew that his spirit was bold and enterprising, yet he must have had uncommon skill and fortune to have penetrated so deep into Mexico, and to preserve a hiding-place so near to the great Castle of Montevideo. And the friends with him must be molded of the finest steel. Who were they? He recalled daring and adventurous spirits among his own comrades in the fatal expedition, but as he ran over every one in his mind he shook his head. It could not be.

It is the truth that, during all this period, inflicting such a tremendous strain upon the captive, John never once tried the key in the door. It was the supreme test of his character, of his restraint, of his power of will, and he passed it successfully. The thread, the dagger, and the key lay together untouched in the bottom of the old mattress, and he waited in all the outward seeming of patience.

The first night was very clear, on the second it rained for six or seven hours. The entire mountainside was veiled in sheets of water or vapor, and John saw nothing beyond his window but the black blur. The third night was clear, but when the morning of the fourth day dawned, John thought, from the clouds that were floating along the mountain slope, it would be rainy again. He hoped that the promise would come true. Darkness and rain favor an escaping prisoner.

The last day was the most terrible of all. Now and then he found his heart pounding as if it would rack itself to pieces. It was difficult to go through with the exercises, and it was still more difficult to preserve calmness of manner in the presence of Diego. Yet he did both. Moreover, his natural steadiness seemed to come back to him as the hour drew near. His was one of those rare and fortunate natures which may be nervous and apprehensive some time before the event, but which become hard and firm when it is at hand. Now John found himself singularly calm. The eternity of waiting had passed, and he was strong and ready.

Diego brought him his supper early, and then, through his loophole, he watched the twilight deepen into the night. And with the night came the rain that the morning and afternoon clouds had predicted. It was a cold rain, driven by a wind that shrieked down the valley, and drops of it, hurled like shot the full width of the slit, struck John in the face. But he liked the cool sharp touch, and he felt sure that the rain would continue all through the night. So much the better.

John’s clothing was old and ragged, and he wore a pair of heelless Mexican shoes. He had no hat or cap. But a prisoner of three lonely years seeking to escape was not likely to think of such things.

He waited patiently through these last hours. He was compelled to judge for himself when midnight had come, but he believed that he had made a close calculation. Then he took a final look through the loophole. The wind, with a mighty groaning and shrieking, was still driving the rain down the slopes, and nothing was visible. Then, with a firm hand, he took from the bed the thread, the knife, and the key. It was not likely that he would have any further use for the thread, but for the sake of precaution he put it in his pocket. He also slipped the dagger into the back of his coat at the neck, after a southwestern fashion which allowed a man to draw and strike with a single motion.

Then, key in hand, he boldly approached the door. Some throbbings of doubt appeared, but he sternly repressed them. Giving himself no time for hesitation, he put the key in the lock and turned his hand toward the right. The key, without any creaking or scraping, turned with it. His heart gave a great leap. He did not know until now that he had really doubted. His joy at the fact showed it. But the miracles were coming true, one after another.

He turned the key around the proper distance, and he heard the heavy bolt slide back. He knew that he would have nothing to do now but pull on the door, yet he paused a few moments as one lingers over a great pleasure, in order to make it greater. He pulled, and the door came back with the same familiar slight creak that he had heard it make so often when Diego entered or left. With an involuntary gesture of one hand, he bade farewell to his cell and stepped into the long, dark corridor upon which the row of cells opened. But for the sake of precaution he locked the cell door again and put the key in his pocket.

Then he drew the slender dagger, clutched it firmly in his right hand, and stepped softly back against the wall, which was in heavy shadow, no light entering it from the narrow barred window at either end. John’s heart beat painfully, but he did not believe that the miracles which were being done in his behalf had yet ended. With his back still toward the wall, and his hand on the hilt of the dagger, he slipped soundlessly along for a few feet. His eyes, growing used to the darkness, made out the posts at the head of a stairway.

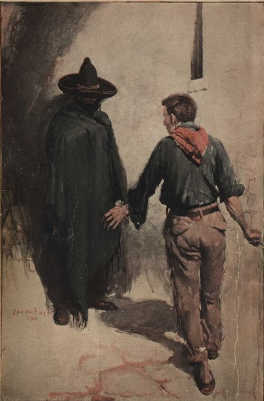

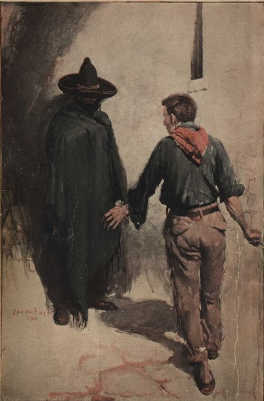

Evidently this was the way he should go, and he paused again. Then his blood slowly chilled within him. A human figure was standing beside one of the posts. He saw it distinctly. It was the figure of a tall man in a long black serape, with a dark handkerchief tied around mouth and chin after the frequent Mexican fashion, and a great sombrero which nearly met the handkerchief. He could see nothing but the narrowest strip of dark face, and in the dusk the man rose to the size of a giant. He was truly a formidable figure to one who had been three years a captive, to one who was armed only with a slender knife.

But the crisis in John Bedford’s life was so great that he advanced straight toward the ominous presence in his path. The man said nothing, but John felt as he approached that the stranger was regarding him steadily. Moreover, he made no motion to draw a weapon. John saw now that one of his hands rested on the post at the stairhead, and the other hung straight down by his side. Surely this was not the attitude of a foe! Perhaps here was merely another in the chain of miracles that had begun to work in his behalf. He advanced a step or two nearer, and the stranger was yet motionless. Another step, and the man spoke in a sharp whisper:

“You are John Bedford?”

“I am,” replied John.

“I’ve been waiting for you. Come. But first take this.”

He drew a double-barreled pistol from his pocket and handed it to John, who did as he was told. The stranger then produced from under his capacious serape another serape and a Mexican hat, which John, acting under his instructions, also put on.

“Now,” said the man, “follow me, and do what I do or what I tell you.”

“You seem to be a brave fellow like your brother; then now is the time to show your courage, and remember, also, that I can do all the talking for both of us. Talking is my great specialty.”

It seemed to John that the stranger spoke in an odd manner, but he liked the sound of his voice, which was at once strong and kind. Why should he not like a man who had come through every imaginable danger to save him from a living death!

“My brother?” whispered John in his eagerness. “Is he still near?”

“I told you I was to do all the talking,” replied the man. “You just follow and step as lightly as you can.”

John obeyed, and, after a descent of a few steps, they came to one of the heavy wooden doors, twelve feet high, but the stranger unlocked it with a key taken from the folds of that invaluable Mexican garment, the serape.

“You didn’t think I’d come on such a trip as this without making full preparations?” said the man with a slight humorous inflection. Then he added: “You’re just a plain, common Mexican, some servant or other, employed about the castle, and you continue to slouch along behind me, who may be an officer for all one knows in this darkness. But first push with me on this door. Push hard and push slowly.”

The heavy door moved back a foot or two, but that was all the stranger wanted. He slipped through the opening, and John came after him. Then the man closed and locked the door again.

“A wise burglar leaves no trail behind him,” he said, “and, although it is too dark for me to see you very well, I want to tell you, Sir John of the Cell, that your figure and walk remind me a great deal of your brother, Sir Philip of the Mountain, the River, and the Plain, as gallant a lad as one may meet in many a long day.”

A question, a half dozen of them leaped to John’s tips, but, remembering his orders, he checked them all there.

“Ah. I see,” said the stranger. “That would certainly tempt any man to ask questions, but, remembering what I told you, you did not ask them. You are of the true metal.

“At least it’s a better night, which, for the uses of poetry, is the same as day. This stairway, John, leads into the great inner court, and then our troubles begin, although we ought to return thanks all the rest of our days for the rain and the heavy darkness. The Mexican officers will see no reason why they shouldn’t remain under shelter, and the Mexican soldiers, in this case, will be glad enough to do as their officers do.”

John now followed his guide with absolute faith. The man spoke more queerly than anybody else that he had ever heard, but everything that he did or said inspired confidence.

They came to the bottom of the stairway and reached the great paved central court, with the buildings of the officers scattered here and there. They stepped into the court, and John fairly shrank within himself when the cold rain lashed into his face. He did not know until then how three years within massive walls had softened and weakened him. But he held himself erect and tautened his nerves, resolved that his comrade should not see that he had shivered.

They saw lights shining from the windows of some of the low buildings, but no human being was visible within the square.

“They’ve all sought cover,” said his rescuer, “and now is our best chance to get through one of the gates. After that there are other walls and ditches to be passed, but, Sir John of the Night, the Wall, the Rain, and the Moat, we’ll pass them. This little plan of ours has been too well laid to go astray. Just the same, you keep that pistol handy.”

John drew the serape about his thin body. It was useful for other things than disguise. Without it the cold would have struck him to the bone. His rescuer led the way across the court until they came to one of the great gates in the wall. The sentinel then was pacing back and forth, his musket on his shoulder, and at intervals he called: “Sentinela alerte!” that his comrades at other gates might hear, and out of the wind and rain came at intervals, though faintly, the responding cry, “Sentinela alerte!” John and the stranger were almost upon this man when the cry “Sentinela alerte!” came from the next gate. He turned quickly as the two dark figures emerged from the darker gloom, but the stranger, with extraordinary dexterity, threw his serape over his face, checking any cry, while his powerful hands choked him into insensibility. At the same time the stranger uttered the answering cry, “Sentinela alerte!”

“You haven’t killed him?” exclaimed John, aghast, as his rescuer let the Mexican slide to the wet earth.

“Not at all,” replied this resourceful man. “The cold rain will bring him back to his senses in five minutes and in ten minutes he will be as well as ever, but in ten minutes we should play our hand, if we ever play it,”

He drew an enormous key from the pocket of the Mexican, unlocked the gate, and, after they had passed out, locked it behind them. Then they stood on the edge of the great moat, two hundred feet wide, twenty feet deep and bank full. The man dropped the key into the water.

“Now, Sir John of the Escape,” he said, “the drawbridge is up, and if it were down it would be too well guarded for us to pass. We must swim. I don’t know how strong you are after a long life in prison, but swim you must. Life is dear, and I think you’ll swim. We’ll take off most of our clothes and tie them with our weapons on our heads. What a wild night! But how good it is for us!”

Crouching in the shadow of the wall they took off most of their clothes, and then each tied them in a package containing his weapons, also, on his head. They were secured with strips torn from John’s rags. Meanwhile, the night was increasing in wildness. John would have viewed it with awe, had not his escape absorbed every thought. The wind groaned through the gorges of the great Sierra, and the cold rain lashed like a whip. The rumblings of thunder came from far and deep valleys between the ridges.

“Now,” said the man, “we’ll drop into the moat together. But let yourself down by your hands as gently as you can, and make no splash when you strike. Now, over we go!”

The two dropped into the water, taking care not to go under, and then began to swim toward the far edge of the moat. John had been a good swimmer, but the water was very cold to his thin body. Nevertheless, he swam with a fairly steady stroke, until they were about halfway across, when he felt cramps creeping over him. But the stranger, who kept close by his side, had been watching, and he put one hand under John’s body. In water the light support became a strong one, and now John swam easily.

They reached the far edge and climbed up on the wall. Here John lay a little while, gasping, while the stranger, who now seemed a very god to him, rubbed his cold body to bring back the warmth. From a point down the bank came the cry “Sentinela alerte!” and from a point in the other direction came the answering cry, “Sentinela alerte!”

“Lie flat,” whispered his rescuer to John, “and we’ll wriggle across fifty feet of ground here until we come to a wooden wall. We’re lost if we stand up, because I think lightning is coming with that thunder.”

He spoke with knowledge, as the thunder suddenly grew louder and the air around them was tinted with phosphorescent light. It was not a flare of lightning, merely its distant reflection, but it was enough to have disclosed them, if they had been standing, to any one ten paces distant. The danger itself gave them new strength, and they quickly crossed the ground to the chevaux de frise, where they crouched against the tall cedar posts. They lay almost flat upon the ground, and they were very glad of the shelter, because the lightning was coming nearer. Now, when the lightning flashed along the mountain slopes, they saw not far away the dim figure of a soldier, and they heard distinctly his cry: “Sentinela alerte!”

“Wait until he goes back.” whispered the stranger. “Then we must climb the wall and climb it quickly. It’s fastened with cross timbers which will give us hold for both hand and foot.”

The lightning tinted the sky once more with its phosphorescent gleam, and they did not see the soldier.

“Now for it!” said the man in a sharp, commanding whisper. “Up with you and over the wall!”

John seized the crosspiece, and in another instant was on the top of a wall of cedar posts twelve feet high. He did not know until afterward that the strong hand of his rescuer had helped him up. In another instant the man was beside him, and then the lightning flared brightly, showing vividly the huge castle, the stone ramparts, the moats and the two figures, naked to the waist, sitting on top of the cedar wall.

“Sentinela alerte!” was shouted far louder than usual, and “Sentinela alerte!” came the reply in the same tone. Two musket shots were fired, and the two figures, one with a red stain on his side, sprang outward from the cedar fence into the second and smaller moat, which was only fourteen feet wide, although its outer wall was an earthwork rising very high above the water. Two or three strong strokes carried them across, and with desperate efforts they climbed up the high bank. They heard shouts, and they knew that when the lightning flared again more shots would be fired at them. It was then that John noticed the red stain on the side of his comrade, and all the reserves of mental strength that made him so much like his brother, Philip, came to his aid. He snatched the package from his head, tore it apart, threw the serape around his body and stood up, erect and defiant, pistol in hand. He would do something for this man who had done so much for him.

The lightning flared again, a long quivering stroke, and the heads of half a dozen men appeared at the crest of the chevaux de frise, not twenty feet away. But John Bedford looked at only one of them. He saw the swarthy, angry face of de Armijo. He seemed to be beckoning with his sword to his men, but a flash like that of the lightning seared John’s whole brain. He remembered how this man had struck him down, when he was chained and helpless, and he fired point blank at the angry face. De Armijo fell back with a terrible cry. He was not dead, but the bullet had plowed full length across his cheek, and he would bear there a terrible red weal all the rest of his life.

The lightning passed, and they were in complete darkness, but John felt a hand on his arm.

“Come,” whispered his rescuer. “You did that well. Prison hasn’t taken any of the manhood from you. We’re outside everything now, and the others are waiting for us.”

They fled away together in the darkness,