The Retreat of the Ten

They stopped at noon beside a shallow brook, more mud than water, to rest, and to eat a little of the cold food in their knapsacks. When the brief meal was ended, Chilton, the Kentuckian, strolled out on the prairie and looked about him.

Except the horses, his was the only upright figure within the circle of the horizon. Far off to the left were patches of squat, thorny bushes, and nearer by ran a fringe of ragged and desolate weeds. Overhead burned a coppery sun, swinging low, and the chief impression upon his mind was that of desolation and loneliness.

“Have I been fighting four years for this?” murmured Chilton.

His eyes followed the circle of the horizon, but everywhere he saw the same—the rolling brown plains, the scanty grass, the desolate weeds and thorn-bush, all shriveling in the fierce rays of the sun. Then he walked back to the brookside.

“How far is it to the border, Chilton?” asked Hicks, the oldest of the party, a thick-set Mississippian of fifty.

“Bloodgood says we ought to make it in three days of hard riding, and he knows the country.”

“So we can,” said Bloodgood, the Texan, “if the horses don’t give out. Texas is a big state and it has good country and bad. This isn’t part of the good.”

“I should think not,” said Chilton, looking again at the sweep of desolation about them. “Let the Yankees have it and welcome, for they’ll take it anyhow. Everything’s Yankee now from the St. Lawrence to the Rio Grande.”

Young Hicks stirred in his sleep and rolled over, where the sun had a fair aim at his face. Old Hicks, his father, put the boy’s broad-brimmed hat over his eyes, and, protected from the glare, he slept peacefully on.

The Dupuy brothers, the South Carolinians, rose and began to buckle the girths of their horses. McCormick, the Florida cracker, a long, thin, yellow man, followed them, and the bustle of the start began.

“Wake the boy,” said Chilton. “We’d better be going.”

“It’s time to mount again, Frank,” said old Hicks, shaking his son, “and then ho for Mexico!”

“Hurrah for Mexico!” said the boy, with enthusiasm, “and may the deuce take this country, since we couldn’t keep the Yankees out of it! I We’ll never live on this soil or under the Yankee flag again! Let’s take an oath on it, pledge our faith to one another. No, let’s sign an agreement.”

The proposal was boyish like the proposer, but it found favor with the sullen and defiant temper of the men.

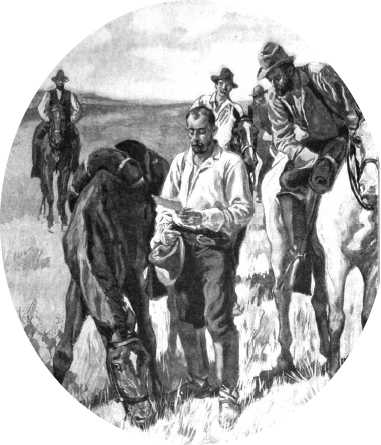

“Good enough,” said Chilton. “I have a note-book and the stub of an old lead pencil, and I guess they’ll do.”

So he drew up a rude statement that the undersigned had served four years in the Confederate army, and, being still loyal to their cause, refused to live in the Yankee republic. Moreover, they took an oath to do all they could to break it up. Then they swore and signed, the whole ten, the boy first and Chilton last. Chilton folded the paper carefully and put it in an inside pocket of his waistcoat, where he also carried a little purse of American gold.

Then they mounted their horses and rode on. The formal oath of renunciation pleased them and soothed their sullen and angry tempers. These men, one of them fifty years old, began to build air-castles—castles in Mexico.

“If enough of the old Confederates would only go down there,” said Taylor, the Georgian, “we might establish, with the start that the country already has, a power which would offset that of the Yankees.”

“It’s not impossible,” said Chilton, meditatively. “We are not the only Southerners on the way to Mexico, and as we succeed others will be drawn after us. In a year or two we ought to have at least fifty thousand Confederates about us, and we’ll be enough to run things. We’ll establish a new power, a great empire, in Mexico.”

Their spirits swelled so high that they broke into a gallop, Bloodgood, the Texan, in the lead, as he was to be the guide to the frontier. They rose from the prairie rather late the next morning. The day was gray and not promising. Young Hicks noticed a raw damp in the air that made him shiver. They ate breakfast, and, mounting, refreshed themselves with a gallop, and then built more castles in Mexico. But the gray in the air thickened into a mist, and the sun looked pale and sick. Young Hicks shivered and wrapped his army blanket around his shoulders.

The cold increased rapidly and the wind began to blow. It raised clouds of dust and sand which turned into curious shapes, and, whirling after one another across the plain, passed out of sight. The horses snorted with fright and cold. The Ten rode in a close huddle, men and horses rubbing against one another, for the sake both of comradeship and of prudence. They came to a low hill which bore a patch of dwarfed trees and interlacing thorn-bushes, and behind it they found some shelter from the storm, now sweeping the prairie with all the fury of a simoom in the Sahara. The sand and dust were driven before the wind in thick clouds, but most of it passed over their heads now, though it made a whistling and shrieking noise like the sound of flying bullets in battle. The cold was bitter and reached the bone. Rain began to fall, but soon changed to showers of hail which beat upon the men and cut their faces. It was as dark as night.

They remained silent, shivering in their wet clothes, until the norther began to abate. The whistle and shriek of the wind died, the air ceased to be a compound of sand and dust, and the sun, breaking a way at last through the clouds, poured a flood of light over the earth which melted the sheets of hail and turned the temperature in an hour from midwinter to midsummer.

“This is bad on those who have fresh-cured wounds,” said Old Hicks to Chilton. He looked anxiously as he spoke at Young Hicks, whose face was pinched and white.

“The boy will stand it all right,” said Chilton, confidently. “He’s a tough sapling, he is.”

Old Hicks seemed to be reassured somewhat, and the Ten rode on. The sunshine was bright enough, and the air warm enough, but Young Hicks was strangely quiet. Presently his teeth began to rattle together.

“He has a chill, a bad one,” said Old Hicks to Chilton.

“Then we must stop and doctor him; it’s the wet clothes,” replied Chilton.

They built a fire of dead bushes, fallen last year, which they coaxed into a blaze, but it did no good; the boy was in the grip of a chill of the very strongest kind, and following the usual course, the icy cold of his body soon began to change to a heat equally fierce.

“We’ve got to camp,” said Chilton to the others. “We can’t go on with the boy in this fix.”

The lad’s fever rose so high that he became delirious, and talked about his home in northern Mississippi which he had not seen in three years.

“Who’s there?” asked Chilton of Old Hicks—meaning the place of which the boy talked.

“Nobody but the old lady.”

“The old lady?”

“Of course, you don’t know—his grandmother, I mean, his mother’s mother. His mother died when he was born, and the old lady raised him. She’s up there now, spry and stout, if she is seventy. It’s up in the hills; not much of a place, but the house is clean and warm, and there’s plenty of green grass, and a spring of cool water running out of the hill back of the house. The old lady wrote me that the war hadn’t touched it.”

“We’ll find better in Mexico,” said Chilton, stoutly.

Bloodgood, the Texan, who had gone for an antelope, came back in an hour, without the game but with something very much more surprising—a party of ranchmen who had been selling cattle on the Mexican border and were now returning northward with their profits.

They traveled in comfortable style and had a wagon loaded with provisions, to which they invited the Ten to help themselves. They produced, too, some quinine from their medicine-chest, with which they dosed Young Hicks, and said he would be all right next day.

The two parties became so fraternal that they pitched their camp together for the night. The leader of the ranchmen, a big, brown-faced man named Allen, offered to take charge of the camp until morning, and Chilton, being weary, was content, and sought sleep, which he soon found. He was awakened once in the night by the sound of men talking, so he thought, but he was so sleepy that it was merely a vague impression, and he closed his eyes again in a moment.

The ranchmen said they would start first in the morning, as they were traveling in a hurry, and when Chilton arose a half dozen of them and the wagon were disappearing over a swell of the earth.

“We’ll eat our breakfast as we go along,” said Allen. “Good-by!”

“We’ll do the same,” said Chilton, and he and his comrades mounted their horses and rode in the other direction. He was silent for half an hour, thinking, and then he said, suddenly:

“How’s the boy?”

There was silence for at least a minute, and then everybody looked at Old Hicks. The man was fifty years old and brown, but a flush came in his face.

“Allen said it wasn’t right for the boy to go on with us,” he answered, apologetically. “Besides, he was talking a lot about the old lady and the place back there on the hill. Well, he’s in the ranchmen’s wagon, lying very comfortable on some bags of meal, going north.”

“But he swore,” said Chilton.

“It don’t count; he’s under twenty-one,” replied Old Hicks, guiltily.

The Nine rode on in silence.

Chilton presently pulled out the piece of paper which contained the agreement and scratched out Young Hicks’s name.

“What are you doing?” asked Carter, the Tennesseean.

“I’m keeping our names out of bad company,” replied Chilton.

Old Hicks heard him, but said nothing, though the flush came again to his face.

Chilton, Bloodgood and others began to discuss the country, which had improved somewhat, but seemed very unfamiliar to Bloodgood. He believed they had wandered from the right direction, and when he examined a rude map which he carried, he was convinced of it.

“There’s nothing to do,” he said, “but to ride southward, and if we keep going we’re sure to come to the Rio Grande at last.”

Water was necessary for the night’s camp, but they saw none; and taking the most conspicuous mound he could find as a center of operations, Chilton sent every man off from it in a direct line, like the spokes radiating from the hub of a wheel, each to return at the end of an hour to the hub. He did not find any, but as he rode back toward the mound at the end of an hour, Carter, coming from the west, hailed him with a shout of triumph, and Chilton’s mind was at rest.

“It runs out of a hillside not more than two miles from here,” said Carter.

All the others had failed, but Carter’s discovery was enough.

“Hello!” Chilton suddenly exclaimed in surprise; “there are only eight of us!”

Each man looked over the little party, and then all said as if by one impulse:

“Old Hicks!”

“What’s that bit of white on the hill there?” asked Carter.

Paul Dupuy dismounted and picked up a scrap of paper, held in place by a thorn.

“There’s writing on it,” he announced.

“What does it say?” asked Chilton.

“‘Luck be with you,’” read Dupuy.

Chilton rode back a little distance in their path on the plain, and saw mixed with the hoof-prints those of one horse going in the other direction.

“He’s gone, boys; we won’t see him anymore,” said Chilton, when he came back.

“I suppose that a man has to look after his son,” said Taylor, the Georgian, to McCorinick.

It was a snug little place that Carter had found, a tiny rivulet spouting out of a hillside and trickling away across the prairie. After all, men and horses, had drunk from the stream, the men tethered the horses in the green grass by the waterside.

As usual, they set a watch, which Paul Dupuy was to keep the first half of the night, and Taylor the second half. It was past one in the morning when Paul Dupuy awakened Taylor and called upon him to take the relief.

“Not a bad spot, eh, Paul?” said Taylor, the Georgian, to Dupuy. “If this hill were a little higher and there were a few more trees, it might pass for a patch of North Georgia, where I used to live.”

“We’re going to build an empire in Mexico, and you won’t see Georgia any more,” replied Dupuy.

“That’s true,” replied Taylor. “I never had much in Georgia, anyway. It was a two-roomed log house, and about twenty acres, I guess. There were ten acres more, but I’d been lawing over it and the case wasn’t settled. That ten acres was claimed by Bill Moore, my neighbor, the meanest man that was ever born, and he went to law. The case had been going on ten years, when he enlisted in the Yankee army and I joined the rebs.”

“What became of him?” asked Dupuy.

“Why, he went back there, of course,” replied Taylor, “for he was too mean a man to get killed. And—thunderation! he’ll be winning that ten-acre suit while I’m off building empires in Mexico.” He said not another word, but taking his rifle in hand, began his duties of sentinel and strode up and down, his eyes somber.

Chilton was first to awake, the light of a brilliant morning sun shining on his eyes.

“Up, boys!” he shouted, and then added: “Hey there, Taylor, all quiet through the night? Here, what the devil has become of Taylor? Why, the man’s gone!”

“His horse is gone, too,” said Bloodgood.

Chilton swore.

“What’s this?” called Kidd, pointing to a tree.

Cut rudely in the soft bark of a tree with the keen point of a knife were some words. Chilton read them aloud:

“Gone to win that ten-acre case.”

He looked around for a meaning, and seeing the light of understanding on Paul Dupuy’s face, said, loudly and sharply:

“Well?”

Dupuy told the story of the ten-acre suit as he had heard it, for the first time, from Taylor the night before.

The brief breakfast was eaten in silence, and then they left the place, the horses turning reluctant eyes toward the green grass and fresh water. After the noon halt, Kidd, the Arkansan, rode up by the side of Chilton, who was in the lead, Chilton liked the man, who was the wildest and roughest of all the party, but who had a certain air of gaiety and humor about him. He came from a frontier portion of Arkansas near the Choctaw line, and throughout the war had been a valiant, even rash soldier.

“Will these Mexicans fight?” he asked Chilton. “I don’t want to be any emperor over people who haven’t got sand.”

“Pretty well,” replied Chiiton. “My father was in the Mexican war and I’ve heard him talk about ’em. I guess if they’re well led, they’ll stand up.”

“There’s a crowd of fellows up in Arkansaw I’d like to have down there with us,” said Kidd, reflectively.

“They’d fight, I suppose,” said Chilton, with a smile.

“Fight!” replied the Arkansan, responding readily to the intended provocation. “I reckon they would! That’s what they’ve been raised on. Why, Chilton, I fought in the feud with the Jewells before I was fourteen years old, and kept on fighting in it until the war came up and both sides went to that; and I reckon if I was back in Arkansaw I’d be fighting in it again, for the Jewells will begin just where they left off, sure!”

He stopped short, kicked his horse in the side, and swore one of his choicest oaths.

“What’s the matter, Kidd?” asked Chilton.

“To think of it!” burst out the Arkansan. “The feud will be raging more than ever because of its four years’ rest, and me, the best fighting-man the Kidds have got, down in Mexico two thousand miles from the scenes of slaughter, building up a throne or some such fool thing for myself! Why, it’s cowardice, rank treason in me!”

“Kidd, what do you mean? What are you talking about?” exclaimed Chilton, stopping his horse and reining him across the path.

“I mean that I’m going to ride straight to Arkansaw!” said Kidd, also stopping his horse. “To Jericho with Mexico and all Mexicans! Do you think they can fight that feud there in Arkansaw without me? If you do, I don’t. Good-by. Don’t any of you boys try to stop me, because it isn’t well for friends to quarrel and hurt one another!”

He waved his hand to his comrades and rode on the back track, the figure of the horse and man growing smaller and smaller until it became a mere black mark against the horizon, and then nothing.

“We are only six now,” said Carter, presently; “but at any rate, we are six men loyal and true.”

They began to talk again of the Rio Grande, which they hoped to reach in a day or so, and they built new castles in Mexico until they stopped for the night. After supper, McCormick produced from his saddle-bags an old and battered little accordion with which he could produce the semblance of a tune or two. With the darkness and the lone prairie as a background adding to the music a certain weirdness and a touch of softness which it had not, the effect was not so bad. Felix Dupuy was lying on his blanket, the light from the camp-fire flickering faintly over his face. He and his brother were of a Huguenot family of Charleston, many generations on American soil, but still French in looks from head to heel, slim, dark and neat. Felix was the youngest of the Ten, next to Young Hicks, and the cracked music of the old accordion seemed to make him forgetful of the prairie. His brother, two years older, was watching him closely, but said nothing until the end of the fifth tune.

“We’ve danced by that many a time in old Charleston, eh, Felix?” said Paul.

“That’s true,” said Felix, “but those good old times can’t come again. The Yankees have Charleston now.”

“But the same people that built up Charleston before will have to build it up again,” said Paul. “The dancing and the music will go on just as they did before the war. Maybe they are going on this very minute. It would be fine, Felix, to walk there again on the old Battery in the cool of the evening with the sea-breeze on your face, and see the pretty girls in white dresses with the red roses in their hair.”

Chilton and Carter kept the watch that night, and when the first bar of sunlight shot up in the east, the six arose and ate their breakfast, all talking freely except Felix Dupuy, who seemed abstracted and gloomy. Then five of them rode briskly away to the south, but Felix Dupuy, the sixth, rode in the other direction.

“Look at Felix Dupuy!” said Bloodgood.

“He’s left us!”

“Is your brother crazy?” Chilton asked of Paul Dupuy.

“Felix was thinking too much about Charleston last night,” replied Paul, his voice full of excuse for his brother, “and he is really out of his head, like a man with a fever. If one were to talk with him sensibly, his mind would clear up and he’d come back.”

“Then try it,” said Chilton.

Paul put his horse to the gallop and the others remained where they were, watching the experiment. Paul rapidly overtook Felix, who seemed not to hear the galloping hoofs behind him. Chilton liked the spirited way in which the elder brother pursued the younger.

Paul rode up beside Felix and the two began to talk earnestly, as the others could tell by the motions of their heads, but the brothers, still talking, rode on, side by side, never looking back until their figures grew misty on the horizon.

“Thunderation!” exclaimed Carter. “They’ve both gone!”

That was the last word spoken for many hours. At the noon halt, they saw a herd of antelope on the horizon, and it occurred to all four that fresh meat would be a good thing to have. McCormick wished the honor of shooting the antelope, and they agreed that he should get the game.

He rode away in a direction somewhat to the right of the herd. McCormick was a saturnine man. His was a solitary nature. He had lived before the war far down on the Florida peninsula, on a spot of sand among the swamps, where he could bask in the warm sunshine through winter and summer alike.

That was the life that suited McCormick, who was created for a Robinson Crusoe, and when he rode off after the antelope the sun that blazed down on him seemed to him to be the same sun that he had known in Florida. He had a little hut there on the sand-spit in which he kept his guns and ammunition and skins and other small property. He had nailed up the door when be went off to the war, and as the hut stood in the wilderness, he had no doubt it was there waiting for him just as he had left it.

The wind was singing a strange tune in the blood of McCormick. He knew all the intricate country around that home of his in the Florida marshes. In a neck of woods between two swamps an old panther roamed at nights. McCormick believed him to be the biggest of his kind in Florida, and four times he had shot at him and missed. Then the war came.

“After I’ve become a great man in Mexico, I’ll go back and see that little hut of mine and shoot that panther,” he said, unconsciously speaking aloud.

He passed over a swell of earth, and it was time to dismount and stalk the antelope. He did not dismount.

“I think I’ll go and see that hut now, and get that panther,” he said. “As well as I can make out, that house of mine in Florida is some thousands of miles east of here, slightly by north.”

He rode east slightly by north.

Chilton, Carter and Bloodgood waited a long time for the return of McCormick, or some evidence that he was still stalking the game. But the sound of no rifle-shot came to their ears; the antelope, though only dim figures against the horizon, seemed undisturbed and grazed peacefully. The three looked at one another with suspicion.

“Let’s see what has become of McCormick,” said Carter.

They rode toward the swell of earth beyond which he had disappeared, and there Bloodgood, who was an old plainsman, dismounted and examined the soft soil.

“He never left his horse’s back,” he announced, “and here goes his trail, to the east and straight away from the antelope.”

It was sufficient. Bloodgood remounted his horse and the Three continued their journey southward, silent and sad.

About the middle of the afternoon, Bloodgood checked his horse and, pointing over the prairie, announced briefly that men were coming. The others were less used than he to the plains, and for a minute or two could see nothing; then they descried dimly moving figures.

“They are Indians coming our way,” said Bloodgood.

The Indians rose fast from the plain as they were approaching at a half gallop. They were all warriors, at least twenty in number, gay with paint, gaudy feathers and bright blankets. Bloodgood uttered a joyful shout, and spurred his horse forward to meet the leader of the band, a large Indian with a fine presence and the features of an old Roman, to whom he gave welcome by the name of Red Dog. Red Dog knew Bloodgood, too, at once, and shook hands with him in the American fashion. Then they talked, and white and red camped together.

“Old Red Dog tells me,” said Bloodgood to Chilton, “that he’s started with this band on the biggest hunting-trip of his life. These men are picked warriors and hunters of the Comanche nation, and they are going to make a complete circuit after the buffalo through northern and western Texas and then into New Mexico to Santa Fé, where they’ll sell the hides.”

Chilton happened to be looking the other way then, and he did not see that Bloodgood’s eyes were glistening. He said it was time for white men and red to part and go their ways, and shaking hands again, they mounted their horses. The Indians turned their faces toward the northwest, formed a kind of hollow square, and Bloodgood was in the center of it.

“Bid your white brother farewell,” said Red Dog, with gravity and dignity, to Chilton and Carter. “He goes with us and his heart goes with us, too.”

“It is true,” called out the Texan, “but wherever you go, boys, I wish you luck.”

The chief said something to his warriors. They burst into a long and thrilling whoop, shook their rifles, waved their lances and dashed off in a wild gallop toward the northwest, the Texan as joyous as any in the wild band.

“Well,” said Chilton, looking at his comrade, “it is only you and I, Carter, Kentucky and Tennessee.”

They rode into the south, sitting erect in their saddles, their faces defiant. About dusk, they selected a camp in a little grove. The night came on, thick and dark, but the fire was a red beam in its center, and the two men sitting beside it basked in its gladness and glow.

“I’ll take a last look at the horses to see that they’re all right,” said Chilton, “and then I think we’d better roll up in our blankets and go to sleep.”

He walked toward the horses, and three yards from the fire the darkness swallowed him up. He was invisible to Carter, but looking back, Chilton could see the red gleam of the coals and the dim figure of Carter sitting beside them. He saw the Tennesseean take something out of his coat and look at it a long time. When he put it back, Chilton returned to the fire.

“Carter,” he said, and his voice was stern, “I’m ashamed of you, to be looking at a picture that way! You, with four years of desperate war just behind you and a greater career Just before you, to be giving way to sloppy sentiment!”

“I’m not ashamed of myself,” said Carter.

“Where does she live?” asked Chilton.

“In Nashville; I knew her there before the war.”

“That was four years ago.”

“But I saw her there just before the battle with Thomas.”

“I guess she has married some other fellow by this time.”

“I guess not; I know she hasn’t.”

There was a strong suggestion of defiance in the Tennesseean’s manner, and Chilton did not deem it wise to say more.

When they saddled their horses the next morning, Carter held out his hand.

“Good-by, Chilton,” he said. “Let’s part friends.”

“Going to see her, I suppose?” said Chilton.

“Yes,” replied Carter; and there was in his voice a note of defiance.

“I don’t think it’s more than one day’s ride to Mexico,” said Chilton, not taking the offered hand.

“But it’s very many days’ ride to Nashville,” said Carter, “and I must start early. See here, Chilton, we’ve been comrades in war a long time and we don’t want to part enemies, now that we have peace.”

Chilton yielded, and shook the offered hand, though reproach was in his eye.

They mounted and rode away in opposite directions, Carter to the north and Chilton to the south. Chilton never looked back. After a while, he took out a sheet of paper and tore it up; he did not want his name to be beside the others.

When Chilton said that Mexico was not more than a day’s ride away, he made his time allowance too large, for by four o’clock in the afternoon he saw a yellow streak on the horizon. The streak broadened into a bar, and then became a wide, shallow river of muddy water which he knew was the Rio Grande. Beyond that yellow river lay the Mexico which was to be the scene of his triumphs. He felt emotion and urged his horse into a trot.

In half an hour he was beside the bank of the yellow stream, and two miles down he saw a tiny steamer about the size of a launch bearing the American flag. Some customs duty, thought Chilton, for smugglers were thick along the frontier.

The river was too deep to ford, but he saw a few adobe huts near by and a large skiff tied to the bank. Two Mexicans came to his hail at one of the huts and began to prepare the boat, when he showed them a small gold coin. One of them pointed to the little steamer still plainly visible on the river.

“The Yankees!” he said, in fair English.

“Yes; what business have they around here?” asked Chilton.

“None,” replied the Mexican. “But they come, without it. We do not like them; they are cowards, robbers.”

“What’s that?” asked Chilton, sharply.

The second Mexican repeated the words of the first, and Chilton, flushing with anger, shouted, “Take it back, you liar!”

The Mexican drew a knife. Chilton, with a swift blow, struck him on the wrist, and the knife flew into the air. The second man came to the assistance of his comrade, but a fist driven into his face by the powerful arm of Chilton sent him head over heels. He sprang lightly to his feet and the two ran away. Chilton looked at their flying forms and rubbed his head thoughtfully.

“Thunderation!” he said. “After fighting four years against the Yankees, here I am, fighting for them!”

He mounted his horse and, riding to the highest point of the bank, gazed long at the Mexican shore.

“Well, it doesn’t look like a very good country, anyway,” he said, at length.

Turning his horse, he rode due north.