12 The One Who Arrived

Henry ware, when his last comrade, hurt and spent, drifted away in the darkness, felt that he was alone in every sense of the word. But the feeling of failure was only momentary. He was unhurt, and the good God had not given him great strength for nothing. He still held the rifle in his left hand above his head and swam with the wide circular sweep of his right arm. The yellow waves of the Ohio surged about him and soon he heard the nasty little spit, spit of bullets upon the water near his head and shoulders. The warriors were firing at him as he swam, but the kindly dusk was still his friend, protecting him from their aim.

He would have dived, swimming under water as long as his lungs would hold air. But he did not dare to wet his precious rifle and ammunition, which he might need the very moment he reached the other shore—if he reached it.

He heard the warriors shooting, and then came the faint sound of splashes as a half dozen leaped into the water to pursue him. Henry changed the rifle alternately from hand to hand in order to rest himself, and continued in a slanting course across the river, drifting a little with the current. He did not greatly fear the swimmers behind him. One could not attack well in the water, and they were likely, moreover, to lose him in the darkness, which was now heavy, veiling either shore from him. Had it not been for the rifle it would have been an easy matter to evade pursuit. Swimming with one arm was a difficult thing to do, no matter how strong and skillful one might be. But the pursuing warriors, who would certainly carry weapons, suffered from the same disadvantage. He heard another faint report, seeming to come from some point miles away, and a bullet struck the water near him, dashing foam in his eyes. It was fired from the bank, but it was the last from that point. He was so far out in the river now that his head became invisible from the shore, and he was helped, also, by the wind, which caused one wave to chase another over the surface of the river.

Henry was now about the middle of the stream, here perhaps half a mile in width, and he paused, except for the drifting of the current, and rested upon arm and shoulder. He looked up. The sky was still darkening, and only a faint silvery mist showed where the moon was poised. Then he looked toward either shore. Both were merely darker walls in the general darkness. He did not see any of the heads of the swimming warriors on the surface of the river, and he believed that they had lost him in the obscurity.

Refreshed by his floating rest of a minute or two, he turned once more toward the Kentucky shore. It was an illusion, perhaps, but it seemed to him that he had been lying at the bottom of a watery trough, and that he was now ascending a sloping surface, broken by little, crumbling waves.

He swam slowly and as quietly as possible, taking care to make no splash that might be heard, and he was beginning to believe that he was safe, when he saw a dark blot on the yellow stream. Far down was another such blot, but fainter, and far up was its like.

They were Indian canoes, and the one before him contained but a single occupant. Henry surmised at once that they were sentinels sent there in advance of the main force, and that the trained eyes of the warriors in the canoes would pierce far in the darkness. It seemed that the way was shut before him, and that he would surely be taken. He felt for an instant or two a sensation of despair. If only the firm ground were beneath his feet he could fight and win! But the watching warrior before him was seated safely in a canoe and could pick him off at ease. Undoubtedly the sentinels had been warned by the shots that a fugitive was coming, and were ready.

But he was not yet beaten. He called once more upon that last reserve of strength and courage, and, as he floated upon his back, holding the rifle just over him, he formed his plan. He must now be quick and strong in the water, and he could not be either if one hand was always devoted to the task of keeping the rifle dry. He must make the sacrifice, and he tied it to his back with a deerskin strap used for that purpose. Then, submerged to his mouth, he swam slowly toward the waiting canoe.

It was a tremendous relief to use both hands and arms for swimming, and fresh energy and hope flowed into every vein. It was a thing terrible in its delicacy and danger that he was trying to do, but he approached it with a bold heart. He was absolutely noiseless. He made not a single splash that would attract attention, and he knew that he was not yet seen. But he could see the Warrior, who was high enough above the water to stand forth from it.

The man was a Wyandot, and to the swimming eyes, so close to the surface of the river, he seemed very formidable, a heavily-built man, naked to the waist, with a thick scalp lock standing up almost straight, an alert face, and the strong curved nose so often a prominent feature of the Indian. One brown, powerful hand grasped a paddle, with an occasional gentle movement of which he held the canoe stationary in the stream against the slow current. A rifle lay across his knees, and Henry knew that tomahawk and knife were at his belt. He not only seemed to be, but was a formidable foe.

Henry paused and sank a little deeper in the water, over his mouth, in fact, breathing only through his nose. He saw that the warrior was wary. Some stray beams of moonlight fell upon the face and lighted up the features more distinctly. It was distinctly the face of the savage, the hunter, a hunter of men. Henry marked the hooked nose, the cruel mouth, and the questing eyes seeking a victim.

He resumed his slow approach, coming nearer and yet nearer. He could not be ten yards from the canoe now, and it was strange that the Indian did not yet see him, His whole body grew cold, but whether from the waters of the river he did not know. Yet another yard, and he was still unseen. Still another yard, and then the questing eyes of the Wyandot rested on the dark object that floated on the surface of the stream. He looked a second time and knew that the head belonged to some fugitive whom his brethren pursued. Triumph, savage, unrelenting triumph filled the soul of the Wyandot. It had been his fortune to make the find, and the trophy of victory should be his. It never entered into his head that he should spare, and, putting the paddle in the boat, he raised the rifle from his knees.

The Wyandot was amazed that the head, which rose only a little more than half above the water, should continue to approach him and his rifle. It came on so silently and with so little sign of propelling power that he felt a momentary thrill of superstition. Was it alive? Was it really a human head with human eyes looking into his own? Or was it some phantasy that Manitou had sent to bewilder him? He shook with cold, which was not the cold of the water, but, quieting his nerves, raised his rifle and fired.

Henry had been calculating upon this effect. He believed that the nerves of the Wyandot were unsteady and, as he saw his finger press the trigger, he shot forward and downward with all the impulse that strong arms and legs could give, the bullet striking spitefully upon the water where he had been.

It was a great crisis, the kind that seems to tune the faculties of some to the highest pitch, and Henry’s mind was never quicker. He calculated the length of his dive and came up with his lungs still half full of air. But he came up, as he had intended, by the side of the canoe.

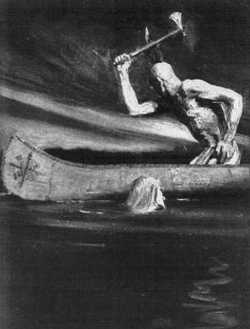

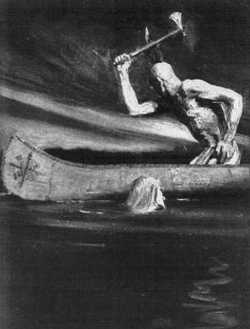

The Wyandot, angry at the dexterity of the trick played upon him, and knowing now that it was no phantasy of Manitou, but a dangerous human being with whom he had to deal, was looking over the side of the canoe, tomahawk in hand, when the head came up on the other side. He whirled instantly at the sound of splashing water and drew back to strike. But a strong arm shot up, clutched his, another seized him by the waist, and in a flash he was dragged into the river.

Henry and the warrior, struggling in the arms of each other, sank deep in the stream, but as they came up they broke loose as if by mutual consent and floated apart. Henry’s head struck lightly against something, and the fierce cry of joy that comes to one who fights for his life and who finds fortune kind, burst from him.

It was the canoe, still rocking violently, but not overturned. He reached out his hand and grasped it. Then, with a quick, light movement, he drew himself on board.

The Wyandot was fifteen feet away, and once more their eyes met. But the positions were reversed, and the soul of the Wyandot was full of shame and anger. He dived as his foe had done, but he came up several feet away from the canoe, and he saw the terrible youth with his own rifle held by the barrel, ready to crush him with a single, deadly blow. The Wyandot perhaps was a fatalist and he resigned himself to the end. He looked up while he awaited the blow that was to send him to another world.

But Henry could not strike. The Indian was wholly helpless now and, his first impulse gone, he dropped the rifle in the canoe, seized the paddle, and with a mighty sweep sent the canoe shooting toward the Kentucky shore. He had turned none too soon. Other canoes drawn by the shot were now coming from both north and south. The Wyandot turned and swam toward one of them, while Henry continued his flight.

Henry was so exultant that he laughed aloud. A few minutes before he had been swimming for his life. Now he was in a canoe, and nothing but the most untoward accident could keep him from reaching the Kentucky shore. One or two shots were fired at long range from the pursuing canoes, but the bullets did not come anywhere near him, and he replied with an ironic shout.

The Wyandot’s bullet pouch and powder horn, torn from him in the struggle, were lying in the boat. Henry promptly seized them, and reloaded the Wyandot’s rifle. Just as he finished the task his canoe struck against the shore, and, as he leaped out, he gave it a push with his foot that sent it into the current. Then carrying the Indian’s rifle in addition to his own, strapped on his back, he darted into the woods.

Once more Henry Ware trod the soil of Kain-tuck-ee, and for an instant or two he did not think of his wounded or exhausted companions behind. Nature had been so kind to him in giving him great physical power, which formed the basis of a sanguine character, that he always and quickly forgot hardships and dangers passed and was ready to meet a new emergency. The muddy Ohio was flowing from him in plentiful rills, but one rifle was loaded, and he had of dry ammunition enough to serve. Moreover, his trifling wound was forgotten. His mind responded to his triumph, and, laughing a little, he shook his captured rifle gleefully.

He stopped three or four hundred yards from the river in a dense clump of oak and elm and listened. He could hear no sound that betokened the approach of the Indians, nor did he consider further pursuit likely. They would be too busy with their intended attack on Fort Prescott to be searching the woods in the night for a lone fugitive, who, moreover, had shown a great capacity for escaping.

The night was dark and a cool wind was blowing. A less hardy body would have been chilled by the immersion in the Ohio, but Henry did not feel it. He was now studying the country, half by observation and half by instinct. It was hilly, as was natural along the course of the river, but the hills seemed to increase in height toward the north and east, that is, up the stream. It was reasonable to infer that Fort Prescott lay in that direction, as its builders would choose a high point for a site.

Henry began his advance, sure that the fort was not far away. The wind rose, drying his yellow hair and blowing it about his face. His clothing, too, began to dry, but he was unconscious of it. The dusky sky served him well. There were but few stars, and the moon was only half-hearted. Nevertheless, he kept well in the thickets, although he veered back toward the Ohio, and now and then he saw its broad surface turned from yellow to silver in the faint moonlight. He saw, also, two or three dark spots near the shore, moving slowly, and he knew that they were Indian canoes. Girty and his force were almost ready for the attack on the fort. A portion of the band was already crossing to the southern shore, and it was likely that the attack would be made from several sides.

Henry increased his pace and came into a little clearing partly filled with low stumps, while others that had either been partially burned or dragged out by the roots lay piled on one side. It looked like a poor little effort of man to struggle with the wilderness, and Henry smiled in the darkness. If this tiny spot were left alone, and it surely would be if Fort Prescott fell, the forest would soon claim it again. But he was glad to see it, because it was a sign that he was approaching the fort.

A little further on he came to a small field of Indian corn, the fresh green blades shimmering in the moonlight and giving forth a pleasant, crooning sound as the wind blew gently upon them. Beyond, on the crest of the hill, he saw a dark line that was a palisade, and beyond that a blur that was roofs. This obviously was Fort Prescott, and Henry examined it with the eye of a general.

The place was located well for defense, on the top of a bare hill, with the forest nowhere nearer than two hundred yards and the underbrush cut cleanly away in order that it might afford no ambush. Henry judged that a spring, rising somewhere inside the palisade, flowed down to the Ohio. He had no fault to find with the place except that it was advanced too far into the Indian country, but that single fault was most serious and might prove fatal.

The fort seemed strong and well built and it was likely that one or two sentinels were on the watch, although he could not see from the outside. One of his hardest problems was now before him, how to enter the fort and give the warning without first being fired upon as an enemy. He had no time to waste, and he decided upon the boldest course of all.

He drew all the air that he could into his lungs, and then, uttering a piercing shout, magnified both in loudness and effect by the quiet night, he rushed directly for the lowest point in the palisade. “Up! up!” he cried. “You are about to be attacked by the tribes! Up! Up! if you would save yourselves!”

Before he was half way to the palisade two heads looked over it, and the muzzles of two long rifles were thrust toward him.

“Don’t shoot!” he cried. “I’m a friend and I bring warning! Don’t you see I’m white?”

It was hard in the darkness of night to see that one so brown as he was white, but the bearers of the rifles were impressed by his forcible words and withdrew their weapons. Henry ran on, and, despite the burden of his two rifles, seized the top of the parapet with his hands and in a moment was over. As he disappeared on the inside, a rifle shot was fired from some point behind, and a bullet whistled where he had been. Henry alighted upon his feet and found facing him two men in buckskin, rifle in hand and ready for instant action. His single glance showed that they were men of resolution, not awed either by his dramatic appearance or the rifle shot fired with such evident hostile intent.

“Who are you?” asked one.

“My name is Henry Ware,” replied Henry rapidly, “and I bring you word that you are about to be attacked by a great force of the allied tribes led by the famous chiefs, Timmendiquas, Yellow Panther, and Red Eagle and the renegades, Girty, Blackstaffe, Eliot, McKee, Quarles, and Wyatt.”

It was a terrible message that he delivered, but his tone was full of truth, and both men paled under their tan. While Henry was speaking, lights were appearing in the log houses within the palisades, and other men, drawn by the shot, were approaching. One, tall, well built, and of middle age, was of military appearance, and Henry knew by the deference paid to him that he must be the chief man of the place.

“What is it?” he asked in a voice of much anxiety.

“The stranger brings news of an attack,” replied one of the sentinels.

“Of an attack by whom?”

“By Indian warriors in great force,” said Henry. “I’ve just escaped from them myself, and I know their plans. They are in the woods now beyond the clearing.”

“To the palisade, some of you,” said the man sharply, “and see that you watch well. I believe that this boy is telling the truth.”

“I would not risk my life merely to tell you a falsehood,” said Henry quietly.

“You do not look like one who would tell a falsehood for any purpose,” said the man.

He looked at Henry with admiration, and the boy’s gaze met his squarely. Nor was it lacking in appreciation. Henry knew that the leader—for such he must be—was a man of fine type.

“My name is Braithwaite, Major Braithwaite,” said the man, “and I believe that I am, in some sort, the commander of the fort which I now fear is planted too deep in the wilderness. I had experience with the savages in the French war and I know how cunning and bold they are.”

Henry learned later that he was from Delaware, that he had earned the rank of major in the great French and Indian war, and that he was brave and efficient. He had opposed the planting of the colony on the river, but, being out-voted, he had accepted the will of the majority.

Major Braithwaite acted with promptness. All the men and larger boys were now coming forth from the houses, bringing their rifles, and as he assigned them to places the Indian war cry rose in the forest on three sides of the fort, and bullets pattered on the wooden palisade.