The Spellbinder

When the special train, bearing the Presidential nominee, made its great loop down through Wyoming and Nebraska, into the central regions of Kansas, where the land rolls away like the waves of the sea and is covered in due season with fields of grain, they came once more into a country abounding in men, and passed little towns, which rose quickly one after another from the prairie.

“And this is Kansas, the home of cranks!” said Churchill.

“I think it is a good thing for a State to have cranks,” said Harley. “It indicates thought and an attempt to solve important problems. Every tree that hears much fruit has some good mixed with the bad.”

“How beautifully metaphorical and allegorical we are becoming!” exclaimed Churchill.

Harley made no rejoiner—he had grown used to Churchill’s cynicism, and returned to his old task of watching the people, who were an unfailing source of interest to him. He had early noticed the difference between the East and the West. The West, wholly detached from the Old World, while the East was not, put its stamp upon its new inhabitants much more quickly, and the whole region seemed to him to have a flavor, lacking in the older and slower East. Moreover, there could be no doubt of its democracy, because every day brought new proofs—it was as much a part of the people’s lives as the pure air of the prairies that flowed through their lungs.

The train was continually thronged with local politicians and others, anxious to see the Candidate, and at a little station in a wheat-field that seemed to have no end they picked up three men, one of whom attracted Harley’s notice at once. He was young, only twenty-four or five, with a bright, quick, eager face, and he was not dressed in the usual careless Western fashion. His trousers were carefully creased, his white shirt was well laundered, and his tie was neat. But he wore that strange combination—not so strange west of the Mississippi—a sack coat and a silk hat at the same time.

The youth was not at all shy, and he early obtained an introduction to Mr. Grayson. Harley thus learned that his name was Moore, Charles Moore, or Charlie, as those with him called him. Most men in the West, unless of special prominence, when presented to Jimmy Grayson merely shook hands, exchanged a word on any convenient topic, and then gave way to others, but this fledgling sought to hold him in long converse on the most vital questions of the campaign.

“That was a fine speech of yours you made at Butte, Mr. Grayson,” he said in the most impulsive manner, “and I indorse every word of it; but are you sure that what you said about Canadian reciprocity will help our party in the great wheat States, such as Minnesota and the Dakotas?”

The Candidate stared at him at first in surprise and some displeasure, but in a moment or two his gaze was changed into a kindly smile. He read well the youth before him. his amusing confidence, his eagerness, and his self-importance that had not yet received a rude check.

“There is something in what you say, Mr. Moore,” replied Jimmy Grayson, in the tone absolutely without condescension that made every man his friend, “but I have considered it, and I think it is better for me to stick to my text. Besides, I am right, you know.”

“Ah, yes, but that is not the point.” exclaimed young Mr. Moore. “One may be right, but one also might keep silent on a doubtful point that is likely to influence many votes. And there are several things in your speeches, Mr. Grayson. with which some of us do not agree. I shall have occasion to address the public concerning them, as you know a number of us are to speak with you while you are passing through Kansas.”

There was a flash in Jimmy Grayson’s eye, but Harley could not tell whether it expressed anger or amused contempt. It was gone in a moment, however, and the Candidate was again looking at the fledgling with a kindly, smiling, and tolerant gaze. But Churchill had thrust his elbow against Harley.

“Oh, the child of the fine and bounding West!” he murmured. “What innocence and what a sense of majesty and power!”

Harley did not deign a reply, but he made the acquaintance by and by of the men who had joined the train with Moore. One of them was a country judge named Bassett, sensible and middle-aged, and he talked freely about the fledgling, whom he seemed to have, in a measure, on his mind. He laughed at first when he spoke of the subject, but he soon became serious.

“Charlie is a good boy,” he said, “but what do you think he is, or, rather, what do you think he thinks he is?”

“I don’t know,” replied Harley.

“Charlie thinks he is a spellbinder, the greatest ever. He’s dreaming by night, and by day too, that he’s the West’s most wonderful orator, and that he’s to swing the thousands with his words. He’s a coming Henry Clay and Daniel Webster rolled into one. He’s read that story about Demosthenes holding the pebble in his mouth, to make himself talk good, and they do say that he slips away out on the prairie, where there’s nobody about, and, with a stone in his mouth, tries to beat the old Greek at his own game. I don’t vouch for the truth of the story, but I believe it.”

Harley could not keep from smiling. “Well, it’s at least an honest ambition,” he said.

“I don’t know about that,” replied the judge, doubtfully, “not in Charlie’s case, because as a spellbinder he isn’t worth shucks. He can’t speak, and he’ll never learn to do it. Besides, he’s leaving a thing he was just made for to chase a rainbow, and it’s breaking his old daddy’s heart.”

“What is it that he was made for?”

“He’s a born telegraph operator. He’s one of the best ever known in the West. They say that at eighteen he was the swiftest in Kansas. Then he went down to Kansas City, and he got along great; now he’s give up a job that was paying him a hundred and fifty a month to start this foolishness. They say he might be a great inventor, too, and here he is trying to speak on politics, when he doesn’t know anything about public questions—and he doesn’t know how to talk, either. I don’t know whether to be mad about it, or just to feel sorry—because Charlie’s father is an old friend of mine.”

Harley showed his feelings. He had seen the round peg in the square hole so many times, with bad results to both the peg and the hole, that every fresh instance grieved him. He was also confirmed in the soundness of Judge Bassett’s opinion by his observation of young Moore, as the journey proceeded. The new spellbinder was anxious to speak, whenever there was an occasion, and often when there was none at all. The discouragement and now and then the open rebukes of his elders could not suppress him. The correspondents, comparing notes, decided that they had never before seen so strong a rage for speaking. He took the whole field of public affairs for his range. He was willing at any time to discuss the tariff, internal revenue, finance, and foreign relations, and avowed himself master of all. Yet Harley saw that he was in these affairs a perfect child, shallow and superficial, and depending wholly upon a few catchwords that he had learned from others. Even the former Populists turned from him. Yet their sour faces when he spoke taught him nothing. He was still, to himself, the great spellbinder, and he looked forward to the day when he, too, a nominee for the Presidency, should charm the multitudes with his eloquence and logic. He had no hesitation in confiding his hopes to Harley. and the correspondent longed to tell him how he misjudged himself, yet he refrained, knowing that it was not his duty, and that even if it were, his words would make no impression.

But in other matters than those of public life and oratory Jimmy Grayson’s people found young Moore likely enough. He was helpful on the train; now and then when the telegraph operators had more material than they could handle he gave them valuable aid; he was a fine comrade, taking good luck and bad luck with equal philosophy and never complaining. “If only he wouldn’t try to speak,” groaned Hobart, for whom he sent a telegraphic message with skill and despatch.

But that very afternoon Moore talked to them on the subject of national finance until they fell into a rage and left the car. That evening Harley was sitting with the Candidate when an old man, bent of figure and gloomy of face, came to them.

“I beg your pardon. Mr. Grayson,” he said. “for intruding on you. but I’ve come to ask a favor. I’m Henry Moore, of Council Grove, the father of Charlie Moore, who was the best telegraph operator in Kansas City, and who is now the poorest public speaker in Kansas.”

The old man smiled, but it was a sad smile. Jimmy Grayson was full of sympathy, and he shook Mr. Moore’s hand warmly.

“I know your son,” he said—“a bright boy.”

“Yes, he’s nothing but a boy,” said his father, as if seeking an excuse. “I suppose all boys must have their foolish spells, but he appears to have his mighty hard and long.”

The old man sighed, and the look of sympathy on Jimmy Grayson’s face deepened.

“Charlie is a good boy,” continued Mr. Moore. “and if he could have this foolish notion knocked out of his head—there’s no other way to get it out—he would be all right, and that’s why I’ve come to you. You know you are to speak at Topeka to-morrow night, in a big hall, and one of the biggest crowds in the West will be there to hear you. Two or three speakers are to follow you, and what do you think that son of mine has done? Somehow or other he has got the committee to put him on the programme right after you, and he says he is going to demolish what he calls your fallacies.”

Harley saw the Candidate’s lips curve a little as if he were about to smile, but the movement was quickly checked. Jimmy Grayson would not willingly hurt the feelings of any man.

“Your boy has that right,” he said to Mr. Moore.

“No, he hasn’t!” burst out the old man. “A boy hasn’t any right to be so light-headed, and I want you, Mr. Grayson, when he has finished his speech, to come right back at him and wipe him off the face of the earth. It will be an easy thing for so big a man as you to do. Charlie doesn’t know a thing about public affairs. He’ll make lots of statements, and every one of ’em will be wrong. Just show him up! Make all the people laugh at him! Just sting him with your words until he turns red in the face! Roll him in the dust and tread on him till he can’t breathe! Then hold him up before all that audience as the biggest and the wildest fool that ever came on a stage. Nothing else will cure him; it will be a favor to him and to me, and I, who love him more than anybody else ask you to do it.”

Harley was tempted to smile, and at the same moment tears came into his eyes. No one could fail to be moved by the old man’s intense earnestness, his florid and mixed imagery, and his appealing look. Certainly Jimmy Grayson was no exception. He glanced at Harley, and saw his expression of sympathy, but the correspondent made no suggestion.

“I appreciate your feelings and your position, Mr. Moore,” he said, “but this is a hard thing that you ask me to do. I cannot trample upon a boy, even metaphorically, in the presence of five thousand people. What would they think of me?”

“They’ll understand. They’ll know why it’s done, and they’ll like you for it. It’s the only way, Mr. Grayson! Either you do it or my boy’s life is ruined!”

Jimmy Grayson walked up and down the room and his face was troubled. He looked again and again at Harley, but the correspondent made no suggestion. At last he stopped.

“I think I can save your son, and promise to make the trial, but I will not say a word more at present. Now don’t ask me anything about it, and never mind the thanks—I understand; maybe I shall have a grown son myself some day to be turned from the wrong path. Good night. I’ll see you again at Topeka. Harley, I wish you would stay a while longer. I want to have further talk with you.”

The Candidate and Harley were in deep converse for some time, and when they finished much of the trouble had disappeared from Jimmy Grayson’s eyes.

“I think it can be done,” he said.

“So do I,” repeated Harley, with confidence.

The next day, which was occupied with the run down to Topeka and occasional stops for speeches at way stations, was uneventful save for the growing obsession of Charlie Moore. He was overflowing with pride and importance. That night in the presence of five thousand people he was going to reply to the great Jimmy Grayson, and to show to them and to him his errors. Mr. Grayson was sound in most things, but there were several in which he should be set right, and he, Charlie Moore, was the man to do it for him. He was suppressed, however, for a few moments only, and then said them over again to the others.

The fledgling proudly produced several printed programmes with his name next to that of the Candidate, and talked to the correspondents of the main points that he would make, until they fled into the next car. But he followed them there, and asked them if they would not like to take in advance a synopsis of his speech in order that they might be sure to telegraph it to their offices in time. All evaded the issue except Harley, who gravely jotted down the synopsis, and, with equal gravity, returned his thanks for Mr. Moore’s consideration.

“I knew you wouldn’t want to miss it.” said the youth; “I come on late, you know, and, besides, I remembered that the difference in time between here and New York is against us.”

Mr. Moore, the father, was on the train throughout the day, but he did not speak to his son. He spent his time in the car in which Jimmy Grayson sat, always silent, but always looking with appeal and pathos at the great leader. His eyes said plainly: “Mr. Grayson, you will not fail me, will you? You will save my son? You will beat him and tread on him until he hasn’t left a single thought of being a famous orator and public leader? Then he will return to the work for which God made him.”

Harley would look at the old man a while, and then return to the next car, where the youth was chattering away to those who could not escape him.

The speech in Topeka was to be of the utmost importance, not alone to those whose own ears would hear it, but to the whole Union, because the Candidate would make a plain declaration upon a number of vexed questions that had been raised within the last week or two. This had been announced in all the press on the authority of Jimmy Grayson himself, and the speech, in full, not a word missing, would have to be telegraphed to all the great newspapers, East and West.

On such important campaigns as that of a Presidential nominee the two great telegraph companies always sent operators with the correspondents in order that they might despatch long messages from small way stations, where the local men were not used to such heavy work. Now Harley and his associates had with them two veterans, Barr and Wynand, from Chicago, who never failed them. They were relieved, too, on reaching Topeka to find that the committee in charge had been most considerate. Some forethoughtful man, whom the correspondents blessed, had remembered the two hours difference in time between Topeka and New York, and against New York, and he had run two wires directly into the hall, and into a private box on the left, where Barr and Wynand could work the instruments, so far from the stage that the clicking would not disturb Jimmy Grayson or anybody else, but would save much time for the correspondents.

The audience gathered early, and it was a splendid Western crowd, big-boned and tanned with the Western winds.

“They have cranks out here, but it’s a land of strong men, don’t you forget that!” said Harley to Churchill, and Churchill did not attempt a sarcastic reply.

They were both sitting at the edge of the stage, and in front of them, nearer the footlights, was young Moore, proud and eager, his fingers moving nervously. His father, too, had found a seat on the stage, but he was in the background, next to the scenery, and being behind the others he was not visible from the floor of the house. There he sat, staring gloomily at his son, and now and then, with a sort of despairing hope, at Jimmy Grayson.

There were some short preliminary speeches and introductions, and then came the turn of the Candidate. The usual flutter of expectation ran over the audience, followed by the usual deep hush, but just at that moment there was an interruption. A boy, in the uniform of a telegraph company, hurried upon the stage.

“You must come at once, sir,” he said. “Mr. Wynand hasn’t turned up! We don’t know what’s become of him! And Mr. Barr has took sick, sudden and bad. The Topeka manager says he’ll get some one here as quick as he can, but he can’t do it under half an hour, anyway!”

The other correspondents stared at each other in dismay, and then at the hired stenographer who was to take down the speech in full. But Harley, always thoughtful and resourceful, rose at once to the crisis. He had noticed Moore lift his head with an expression of lively interest at the news of the disaster, and stepping forward at once he put his hand on the fledgling’s shoulder.

“Mr. Moore,” he exclaimed, in stirring appeal, “this is a crisis and you must save us! You have eaten with us and you have lived with us, and you cannot desert us now! We have all heard that you are a great operator, the greatest in the West! You must take Mr. Grayson’s speech! What a triumph it will be for you to send what he says and then get upon the stage and demolish it afterwards!”

The feeling in Harley’s voice was real, and the boy was thrilled by it and the situation. Every natural impulse in him responded. It was the chivalrous thing for him to do, and an easy one. He could send a speech as fast as the fastest man living could deliver it. He rose without a word, his heart thrilling with thoughts of the coming battle, in which he felt proudly that he would be a victor, and made his way to the telegrapher’s box.

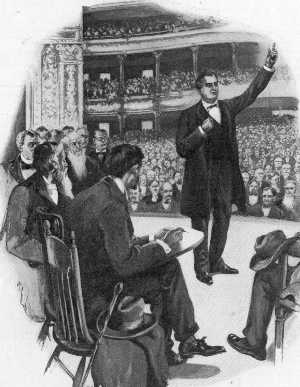

Moore was a Topeka boy, and nearly everybody in the audience knew him. When they saw him take his seat at one of the instruments their quick Western minds divined what he was going to do, and the roar of applause that they had just given to the Candidate, who was now on his feet, was succeeded by another, but the second was for Charlie the telegraph operator.

The fledgling had no time to think. He had scarcely settled himself in his chair when the deep, full voice of Jimmy Grayson filled the great hall, and he was launched upon a speech for which the whole Union was waiting. The shorthand man was already deep in his work and the copy began to come. But the boy felt no alarm; he was not even fluttered; the feel of the key was good, and the atmosphere of that box which enclosed the telegraph apparatus came sweet to his nostrils. He called up Kansas City, from which the speech would be repeated to the greater cities, and with a sigh of deep satisfaction settled to his task.

They tell yet in Western cities of Charlie Moore’s great exploit. The Candidate was in splendid form that night and his speech came rushing forth in a torrent. The missing Wynand was still missing and the luckless Barr was still ill, but the fledgling sat alone in the box. his face bent over the key, oblivious to the world around him, and sent it all. Through him ran the fire of battle and great endeavor. He heard the call and replied. He never missed a word. He sent them hot across the prairie, over the slopes and ridges, and across the muddy Kaw into Kansas City. And there in the general office the manager muttered more than once:

“That fellow is doing great work! How he saves time!”

The audience liked Jimmy Grayson’s speech, and again and again the applause swelled and echoed. Then they noticed how the boy in the telegrapher’s box—a boy of their own—was working. Mysterious voices, too, began to spread, among them the news that Charlie Moore had saved the day, or, rather, the night, and now and then in Jimmy Grayson’s pauses, cries of “Good boy, Charlie!” arose.

Harley, while doing his writing, nevertheless kept a keen eye upon all the actors in the drama. He saw the light of hope appear more strongly upon old man Moore’s face, and then turn into a glow as he beheld his son doing so well.

The Candidate spoke on and on. He had begun at nine o’clock, but it was a great and important speech, and no one left the hall. Eleven o’clock and then midnight, and Jimmy Grayson was still speaking. But it was not his night alone; it belonged to two men, and the other partner was Charlie Moore, who fulfilled his task equally well, and whom the audience still noticed.

The boy was thinking only of his duty that he was doing so well. The victory was his, as he knew that it would be. He kept even with the speech. Hardly had the last word of the sentence left Jimmy Grayson’s lips before the first of it was flying to Kansas City, and in newspaper offices, fifteen hundred miles away, they were putting every paragraph in type before it was a half hour old.

The boy, by and by, as the words passed before him on the written page, began to notice what a great speech it was. How the sentences went to the heart of things! How luminous and striking was the phraseology! And around him he heard, as if in a dream, the liquid notes of that wonderful golden voice. Suddenly, like a stroke of lightning, he realized how empty were his own thoughts, how bare and hard his speech, and how thin and flat his voice. His heart sank, with a plunge, and then rose again as his fingers touched the familiar key, and the answering touch thrilled back through his body. He glanced at the audience and saw many faces gazing up at him, and on their faces was a peculiar look. Again the thrill ran through him, and, bending his head lower, he sent the words faster than ever on their Eastern journey.

At last Jimmy Grayson stopped, and then the audience roared its applause for the speaker, and when the echoes died, someone—it was Judge Bassett—sprang upon a chair and exclaimed:

“Gentlemen, we have cheered Mr. Grayson, and he deserves it, but there is another whom we ought to cheer too. You have seen Charlie Moore, a Topeka boy, one of our own there in the box, sending the speech to the world that was waiting for it. Perhaps you do not know that if he had not helped us to-night the world would have had to wait too long.”

They dragged young Moore, amid the cheers, upon the stage, and then when the hush came the Candidate said:

“You seem to know him already, but as all the speaking of the evening is now over, I wish to introduce to you again Mr. Charlie Moore, the greatest telegraph operator in the West, the genius of the key, a man destined to rise to the highest place in his profession.”

When the last echo of the last cheer died there died with it the last ambition of Charlie Moore to be a spellbinder, and straight before him—broad, smooth, and alluring—lay the road for which his feet were fitted.

But the words most grateful to Jimmy Grayson were the thanks of the fledgling’s old father.