3 Sanctuary

Ned Fulton’s sleep was that of exhaustion, and it lasted long. Although fine snow yet fell outside, and the raw wind blew it about, a pleasant warmth pervaded the snug alcove, made by the back of the pew in which he lay. He had been fortunate indeed to find such a place, because the body of the church was gloomy and cold. But he did not hear the winds, and no thought of the snow troubled him, as he slept on hour after hour.

The night passed, the light snow had ceased, no trace of it was left on the earth, and the brilliant sunshine flooded the ancient capital with warmth. People went about their usual pursuits. Old men and old women sold sweets, hot coffee, and tortillas and frijoles, also hot, in the streets. Little plaster images of the saints and the Virgin were exposed on trays. Donkeys loaded with vegetables, that had been brought across the lakes, bumped one another in the narrow ways. Many officers in fine uniforms and many soldiers in uniforms not so fine could be seen.

Whatever else Mexico might be it was martial. The great Santa Anna whom men called another Napoleon now ruled, and there was talk of war and glory. Much of it was vague, but of one thing they were certain. Santa Anna would soon crush the mutinous Texans in the wild north. Gringos they were, always pushing where they were not wanted, and, however hard their fate, they would deserve it. The vein of cruelty which, despite great virtues, has made Spain a by-word among nations, showed in her descendants.

But the boy, Edward Fulton, sleeping in the chapel of the great cathedral, knew nothing of it all. Nature, too long defrauded, was claiming payment of her debt, and he slept peacefully on, although the hours passed and noon came.

The church had long been open. Priests came and went in the aisles, and entered some of the chapels. Worshipers, most of them women, knelt before the shrines. Service was held at the high altar, and the odor of incense filled the great nave. Yet the boy was still in sanctuary, and a kindly angel was watching over him. No one entered the chapel in which he slept.

It was almost the middle of the afternoon when he awoke. He heard a faint murmur of voices and a pleasant odor came to his nostrils. He quickly remembered everything, and, stirring a little on his wooden couch he found a certain stiffness in the joints. He realized however that all his strength had come back.

But Ned Fulton understood, although he had escaped from prison and had found shelter and sanctuary in the cathedral, that he was yet in an extremely precarious position. The murmur of voices told him that people were in the church, and he had no doubt that the odor came from burning incense.

A little light from the narrow window fell upon him. It came through colored glass, and made red and blue splotches on his hands, at which he looked curiously. He knew that it was a brilliant day outside, and he longed for air and exercise, but he dared not move except to stretch his arms and legs, until the stiffness and soreness disappeared from his joints. Contact with Spaniard and Mexican had taught him the full need of caution.

He was very hungry again, and now he was thankful for his restraint of the night before. He ate the rest of the food in his pockets and waited patiently.

Ned knew that he had slept a long time, and that it must be late in the day. He was confirmed in his opinion by the angle at which the light entered the window, and he decided that he would lie in the pew until night came again. It was a trying test. School his will as he would he felt at times that he must come from his covert and walk about the chapel. The narrow wooden pew became a casket in which he was held, and now and then he was short of breath. Yet he persisted. He was learning very young the value of will, and he forced himself every day to use it and increase its strength.

In such a position and with so much threatening him his faculties became uncommonly keen. He heard the voices more distinctly, and also the footsteps of the priests in their felt slippers. They passed the door of the chapel in which he lay, and once or twice he thought they were going to enter, but they seemed merely to pause at the door. Then he would hold his breath until they were gone.

At last and with infinite joy he saw the colored lights fade. The window itself grew dark, and the murmur in the church ceased. But he did not come forth from his secure refuge until it was quite dark. He staggered from stiffness at first, but the circulation was soon restored. Then he looked from the door of the chapel into the great nave. An old priest in a brown robe was extinguishing the candles. Ned watched him until he had put out the last one, and disappeared in the rear of the church.

Then he came forth and standing in the great, gloomy nave tried to decide what to do next. He had found a night’s shelter and no more. He had escaped from prison, but not from the City of Mexico, and his Texas was yet a thousand miles away.

Ned found the little door by which he had entered, and passed outside, hiding again among the trees of the Zocalo. The night was very cold and he shivered once more, as he stood there waiting. The night was so dark that the cathedral was almost a formless bulk. But above it, the light in the slender lantern shone like a friendly star. While he looked the great bell of Santa Maria de Guadalupe in the western tower began to chime, and presently the smaller bell of Dona Maria in the eastern tower joined. It was a mellow song they sung and they sang fresh courage into the young fugitive’s veins. He knew that he could never again see this cathedral built upon the site of the great Aztec teocalli, destroyed by the Spaniards more than three hundred years before, without a throb of gratitude.

Ned’s first resolve was to take measures for protection from the cold, and he placed his silver dollars in his most convenient pocket. Then he left the trees and moved toward the east, passing in front of the handsome church Sagrario Metropolitano, and entering a very narrow street that led among a maze of small buildings. The district was lighted faintly by a few hanging lanterns, but as Ned had hoped, some of the shops were yet open. The people who sat here and there in the low doorways were mostly short of stature and dark and broad of face. The Indian in them predominated over the Spaniard, and some were pure Aztec. Ned judged that they would not take any deep interest in the fortunes of their rulers, Spanish or Mexican, royalist or republican.

He pulled his cap over his eyes and a little to one side, and strolled on, humming an old Mexican air. His walk was the swagger of a young Mexican gallant, and in the dimness they would not notice his Northern fairness. Several pairs of eyes observed him, but not with disapproval. They considered him a trim Mexican lad. Some of the men in the doorways took up the air that he was whistling and continued it.

He saw soon the place for which he was looking, a tiny shop in which an old Indian sold serapes. He stopped in the doorway, which he filled, took down one of the best and heaviest and held out the number of dollars which he considered an adequate price. The Indian shook his head and asked for nearly twice as much. Ned knew how long they bargained and chaffered in Mexico and what a delight they took in it. After an hour’s talk he could secure the serape, at the price he offered, but he dared not linger in one place. Already the old Indian was looking at him inquiringly. Doubtless he had seen that this was no Mexican, but Ned judged shrewdly that he would not let the fact interfere with a promising bargain.

The boy acted promptly. He added two more silver dollars to the amount that he had proffered, put the whole in the old Indian’s palm, took down the serape, folded it over his arm, and with a “gracias, senor,” backed swiftly out of the shop. The old Indian was too much astonished to move for at least a half minute. Then tightly clutching the silver in his hand he ran into the street. But the tall young senor, with the serape already wrapped around his shoulders, was disappearing in the darkness. The Indian opened his palm and looked at the silver. A smile passed over his face. After all, it was two good Spanish dollars more than he had expected, and he returned contentedly to his shop. If such generous young gentlemen came along every night his fortune would soon be made.

Ned soon left the shop far behind. It was a fine serape, very large, thick and warm, and he draped himself in it in true Mexican fashion. It kept him warm, and, wrapped in its folds, he looked much more like a genuine Mexican. He had but little money left, but among the more primitive people beyond the capital one might work his way. If suspected he could claim to be English, and Mexico was not at war with England.

He bought a sombrero at another shop with almost the last of his money, and then started toward La Viga, the canal that leads from the lower part of the city toward the fresh water lakes, Chalco and Xochimilco. He hoped to find at the canal one of the bergantins, or flat-bottomed boats, in which vegetables, fruit and flowers were brought to the city for sale. They were good-natured people, those of the bergantins, and they would not scorn the offer of a stout lad to help with sail and oar.

Hidden in his serape and sombrero, and, secure in his knowledge of Spanish and Mexican, he now advanced boldly through the more populous and better lighted parts of the city. He even lingered a little while in front of a cafe, where men were playing guitar and mandolin, and girls were dancing with castanets. The sight of light and life pleased the boy who had been so long in prison. These people were diverting themselves and they smiled and laughed. They seemed to have kindly feelings for everybody, but he remembered that cruel Spanish strain, often dormant, but always there, and he hastened on.

Three officers, their swords swinging at their thighs, came down the narrow street abreast. At another time Ned would not have given way, and even now it hurt him to do so, but prudence made him step from the sidewalk. One of them laughed and applied an insulting epithet to the “peon,” but Ned bore it and continued, his sombrero pulled well down over his eyes.

His course now led him by the great palace of Iturbide, where he saw many windows blazing with light. Several officers were entering and chief among them he recognized General Martin Perfecto de Cos, the brother-in-law of Santa Anna, whom Ned believed to be a treacherous and cruel man. He hastened away from such an unhealthy proximity, and came to La Viga.

He saw a rude wharf along the canal and several boats, all with the sails furled, except two. These two might be returning to the fresh water lakes, and it was possible that he could secure passage. The people of the bergantins were always humble peons and they cared little for the intrigues of the capital.

It was now about eleven o’clock and the night had lightened somewhat, a fair moon showing. Ned could see distinctly the boats or bergantins as the Mexicans called them. They were large, flat of bottom, shallow of draft, and were propelled with both sail and oar. He was repulsed at the first, where a surly Mexican of middle age told him with a curse that he wanted no help, but at the next which had as a crew a man, a woman, evidently his wife, and two half-grown boys, he was more fortunate. Could he use an oar? He could. Then he might come, because there was little promise of wind, and the sails would be of no use. A strong arm would help, as it was sixteen miles down La Viga to the Lake of Xochimilco, on the shores of which they lived. The boys were tired and sleepy, and he would serve very well in their stead.

Ned took his place in the boat, truly thankful that in this crisis of his life he knew how to row. He saw that his hosts, or rather those for whom he worked, were an ordinary peon family, at least half Indian, sluggish of mind and kind of heart. They had brought vegetables and flowers to the city, and now they were thriftily returning in the night to their home on the lake that Benito Igarritos and his sons might not miss the next day from their work.

Igarritos and Ned took the oars. The two boys stretched themselves on the bottom of the boat and were asleep in an instant. Juana, the wife, spread a serape over them, and then sat down in Turkish fashion in the center of the bergantin, a great red and yellow reboso about her head and shoulders. Sometimes she looked at her husband, and sometimes at the strange boy. He had spoken to them in good Mexican, he dressed like a Mexican and he walked like a Mexican, but she had not been deceived. She knew that the Mexican part of him ended with the serape and sombrero. She wondered why he had come, and why he was anxious to go to the Lake of Xochimilco. But she reflected with the patience and resignation of an oppressed race that it was no business of hers. He was a good youth. He had spoken to her with compliments as one speaks to a lady of high degree, and he bent manfully on the oar. He was welcome. But he must have a name and she would know it.

“What do you call yourself?” she asked.

“William,” he replied. “I come from a far country, England, and it is my pleasure to travel in new lands and see new peoples.”

“Weel-le-am,” she said gravely, “you are far from your friends.”

Ned bent his head in assent. Her simple words made him feel that he was indeed far from his own land and surrounded by a thousand perils. The woman did not speak again and they moved on with an even stroke down the canal which had an uniform width of about thirty feet. They were still passing houses of stone and others of adobe, but before they had gone a mile they were halted by a sharp command from the shore. An officer and three soldiers, one of whom held a lantern, stood on the bank.

Ned had expected that they would be stopped. These were revolutionary times and people could not go in or out of the city unnoticed. Particularly was La Viga guarded. He knew that his fate now rested with Benito Igarritos and his wife Juana, but he trusted them. The officer was peremptory, but the bergantin was most innocent in appearance. Merely a humble vegetable boat returning down La Viga after a successful day in the city. “Your family?” Ned heard the officer say to Benito, as he flashed the lantern in turn upon every one.

Taciturn, like most men of the oppressed races, Benito nodded, while his wife sat silent in her great red and yellow reboso. Ned leaned carelessly upon the oar, but his face was well hid by the sombrero, and his heart was throbbing. When the light of the lantern passed over him he felt as if he were seared by a flame, but the officer had no suspicion, and with a gruff “Pass on” he withdrew from the bank with his men. Benito nodded to Ned and they pulled again into the center of La Viga. Neither spoke. Nor did the woman.

Ned bent on the oar with renewed strength. He felt that the greatest of his dangers was now passed, and the relief of the spirit brought fresh strength. The night lightened yet more. He saw on the low banks of the canal green shrubs and many plants with spikes and thorns. It seemed to him characteristic of Mexico that nearly everything should have its spikes and thorns. Through the gray night showed the background of the distant mountains.

They overtook and passed two other bergantins returning from the city and they met a third on its way thither with vegetables for the morning market. Benito knew the owners and exchanged a brief word with everyone as he passed. Ned pulled silently at his oar.

When it was far past midnight Ned felt a cool breeze rising. Benito began to unfurl the sail.

“You have pulled well, young senor,” he said to Ned, “but the oar is needed no more. Now the wind will work for us. You will sleep and Carlos will help me.”

He awoke the elder of the two boys. Ned was so tired that his arms ached, and he was glad to rest. He wrapped his heavy serape about himself, lay down on the bottom of the boat, pillowed his head on his arm, and went to sleep.

When he awoke, it was day and they were floating on a broad sheet of shallow water, which he knew instinctively was Xochimilco. The wind was still blowing, and one of the boys steered the bergantin. Benito, Juana and the other boy sat up, with their faces turned toward the rosy morning light, as if they were sun-worshipers. Ned also felt the inspiration. The world was purer and clearer here than in the city. In the early morning the grayish, lonely tint which is the prevailing note of Mexico, did not show. The vegetation was green, or it was tinted with the glow of the sun. Near the lower shores he saw the Chiampas or floating gardens.

Benito turned the bergantin into a cove, and they went ashore. His house, flat roofed and built of adobe, was near, standing in a field, filled with spiky and thorny plants. They gave Ned a breakfast, the ordinary peasant fare of the country, but in abundance, and then the woman, who seemed to be in a sense the spokesman of the family, said very gravely:

“You are a good boy, Weel-le-am, and you rowed well. What more do you wish of us?”

Benito also bent his dark eyes upon him in serious inquiry. Ned was not prepared for any reply. He did not know just what to do and on impulse he answered:

“I would stay with you a while and work. You will not find me lazy.”

He waved his hand toward the spiky and thorny field. Benito consulted briefly with his wife and they agreed. For three or four days Ned toiled in the hot field with Benito and the boys and at night he slept on the floor of earth. The work was hard and it made his body sore. The food was of the roughest, but these things were trifles compared with the gift of freedom which he had received. How glorious it was to breathe the fresh air and to have only the sky for a roof and the horizon for walls!

Benito and the older boy again took the bergantin loaded with vegetables up La Viga to the city. They did not suggest that Ned go with them. He remained working in the field, and trying to think of some way in which he could obtain money for a journey. The wind was good, the bergantin traveled fast, and Benito and his boy returned speedily. Benito greeted Ned with a grave salute, but said nothing until an hour later, when they sat by a fire outside the hut, eating the tortillas and frijoles which Juana had cooked for them.

“What is the news in the capital?” asked Ned.

Benito pondered his reply.

“The President, the protector of us all, the great General Santa Anna, grows more angry at the Texans, the wild Americans who have come into the wilderness of the far North,” he replied. “They talk of an army going soon against them, and they talk, too, of a daring escape.”

He paused and contemplatively lit a cigarrito.

“What was the escape?” asked Ned, the pulse in his wrist beginning to beat hard.

“One of the Texans, whom the great Santa Anna holds, but a boy they say he was, though fierce, slipped between the bars of his window and is gone. They wish to get him back; they are anxious to take him again for reasons that are too much for Benito.”

“Do you think they will find him?”

“How do I know? But they say he is yet in the capital, and there is a reward of one hundred good Spanish dollars for the one who will bring him in, or who will tell where he is to be found.”

Benito quietly puffed at his cigarrito and Juana, the cooking being over, threw ashes on the coals.

“If he is still hiding within reach of Santa Anna’s arm,” said Ned, “somebody is sure to betray him for the reward.”

“I do not know,” said Benito, tossing away the stub of his cigarrito. Then he rose and began work in the field.

Ned went out with the elder boy, Carlos, and caught fish. They did not return until twilight, and the others were already waiting placidly while Juana prepared their food. None of them could read; they had little; their life was of the most primitive, but Ned noticed that they never spoke cross words to one another. They seemed to him to be entirely content.

After supper they sat on the ground in front of the adobe hut. The evening was clear and already many stars were coming into a blue sky. The surface of the lake was silver, rippling lightly. Benito smoked luxuriously.

“I saw this afternoon a friend of mine, Miguel Lampridi,” he said after a while. “He had just come down La Viga from the city.”

“What news did he bring?” asked Edward.

“They are still searching everywhere for the young Texan who went through the window—Eduardo Fulton is his name. Truly General Santa Anna must have his reasons. The reward has been doubled.”

“Poor lad,” spoke Juana, who spoke seldom. “It may be that the young Texan is not as bad as they say. But it is much money that they offer. Someone will find him.”

“It may be,” said Benito. Then they sat a long time in silence. Juana was the first to go into the house and to bed. After a while the two boys followed. Another half hour passed, and Ned rose.

“I go, Benito,” he said. “You and your wife have been good to me, and I cannot bring misfortune upon you. Why is it that you did not betray me? The reward is large. You would have been a rich man here.”

Benito laughed low.

“Yes, it would have been much money,” he replied, “but what use have I for it? I have the wife I wish, and my sons are good sons. We do not go hungry and we sleep well. So it will be all the days of our life. Two hundred silver dollars would bring two hundred evil spirits among us. Thy face, young Texan, is a good face. I think so and my wife, Juana, who knows, says so. Yet it is best that you go. Others will soon learn, and it is hard to live between close stone walls, when the free world is so beautiful. I will call Juana, and she, too, will tell you farewell. We would not drive you away, but since you choose to go, you shall not leave without a kind word, which may go with you as a blessing on your way.”

He called at the door of the adobe hut. Juana came forth. She was stout, and she had never been beautiful, but her face seemed very pleasant to Ned, as she asked the Holy Virgin to watch over him in his wanderings.

“I have five silver dollars,” said Benito. “They are yours. They will make the way shorter.”

But Ned refused absolutely to accept them. He would not take the store of people who had been so kind to him. Instead he offered the single dollar that he had left for a heavy knife like a machete. Benito brought it to him and reluctantly took the dollar.

“Do not try the northern way, Texan,” he said, “it is too far. Go over the mountains to Vera Cruz, where you will find passage on a ship.”

It seemed good advice to Ned, and, although the change of plan was abrupt, he promised to take it. Juana gave him a bag of food which he fastened to his belt under his serape, and at midnight, with the blessing of the Holy Virgin invoked for him again, he started. Fifty yards away he turned and saw the man and woman standing before their door and gazing at him. He waved his hand and they returned the salute. He walked on again a little mist before his eyes. They had been very kind to him, these poor people of another race.

He walked along the shore of the lake for a long time, and then bore in toward the east, intending to go parallel with the great road to Vera Cruz. His step was brisk and his heart high. He felt more courage and hope than at any other time since he had dropped from the prison. He had food for several days, and the possession of the heavy knife was a great comfort. He could slash with it, as with a hatchet.

He walked steadily for hours. The road was rough, but he was young and strong. Once he crossed the pedregal, a region where an old lava flow had cooled, and which presented to his feet numerous sharp edges like those of a knife. He had good shoes with heavy soles and he knew their value. On the long march before him they were worth as much as bread and weapons, and he picked his way as carefully as a walker on a tight rope. He was glad when he had crossed the dangerous pedregal and entered a cypress forest, clustering on a low hill. Grass grew here also, and he rested a while, wrapped in his serape against the coldness of the night.

He saw behind and now below him the city, the towers of the churches outlined against the sky. It was from some such place as this that Cortez and his men, embarked upon the world’s most marvelous adventure, had looked down for the first time upon the ancient city of Tenochtitlan. But it did not beckon to Ned. It seemed to him that a mighty menace to his beloved Texas emanated from it. And he must warn the Texans.

He sprang to his feet and resumed his journey. At the eastern edge of the hill he came upon a beautiful little spring, leaping from the rock. He drank from it and went on. Lower down he saw some adobe huts among the cypresses and cactus. No doubt their occupants were sound asleep, but for safety’s sake he curved away from them. Dogs barked, and when they barked again the sound showed they were coming nearer. He ran, rather from caution than fear, because if the dogs attacked he wished to be so far away from the huts that their owners would not be awakened.

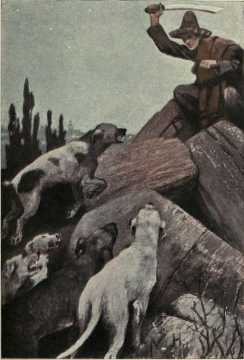

Now he gave thanks that he had the machete. He thrust his hands under the serape and clasped its strong handle. It was a truly formidable weapon. He came to another little hill, also clothed in cypress, and began to ascend it with decreased speed. The baying of the dogs was growing much louder. They were coming fast. Near the summit he saw a heap of rock, probably an Aztec tumulus, six or seven feet high. Ned smiled with satisfaction. Pressed by danger his mind was quick. He was where he would make his defense, and he did not think it would need to be a long one.

He settled himself well upon the top of the tumulus and drew his machete. The dogs, six in number, coursed among the cypresses, and the leader, foam upon his mouth, leaped straight at Ned. The boy involuntarily drew up his feet a little, but he was not shaken from the crouching position that was best suited to a blow. As the hound was in mid-air he swung the machete with all his might and struck straight at the ugly head. The heavy blade crashed through the skull and the dog fell dead without a sound. Another which leaped also, but not so far, received a deep cut across the shoulder. It fell back and retreated with the others among the cypresses, where the unwounded dogs watched with red eyes the formidable figure on the rocks.

But Ned did not remain on the tumulus more than a few minutes longer. When he sprang down the dogs growled, but he shook the machete until it glittered in the moonlight. With howls of terror they fled, while he resumed his journey in the other direction.

Near morning he came into country which seemed to him very wild. The soil was hard and dry, but there was a dense growth of giant cactus, with patches here and there of thorny bushes. Guarding well against the spikes and thorns he crept into one of the thickets and lay down. He must rest and sleep and already the touch of rose in the east was heralding the dawn. Sleep by day and flight by night. He was satisfied with himself. He had really succeeded better so far than he had hoped, and, guarded by the spikes and thorns, slumber took him before dawn had spread from east to west.