11 The Young Slave

Will’s first sign of returning consciousness was a frightful headache, and he did not open his eyes, but, instead, moved his hand toward the pain as one is tempted to bite down on a sore tooth. It was in the top of his head, and his fingers touched a bandage. Without thinking he pulled at it, and the pain, so far from being confined to one spot, shot through his whole body. Then he lay still, with his eyes yet shut, and the agony decreased until it was confined to a dull throbbing in the original spot.

He tried to gather together his scattered and wandering faculties and coordinate them to such an extent that he could produce thought. It required a severe effort, and made his head ache worse than ever, but he persisted until he remembered that he had been creeping through bushes in search of a sound, or the cause of a sound. But memory stopped there and presently faded quite away. Another effort and he lifted his mind back on the track. Then he remembered the slight sound in the bushes near him, the shadow of a figure and a stunning blow. Beyond that his memory despite all his whipping and driving, would not go, because there was nothing on which to build.

He opened his eyes which were heavy-lidded and painful for the time, and saw the figures of Indians that seemed to be standing far above him. Then he knew that he was lying flat upon his back, and that his sick brain was exaggerating their height, because they truly appeared to him in the guise of giants. He tried to move his feet but found that they were bound tightly together, and the effort gave him much pain. Then he was in truth a captive, the captive of those who cared little for his sufferings. It was true they had bound up his head, but Indians often gave temporary relief to the wounds of their prisoners in order that they might have more strength to make the torture long.

His vision cleared gradually, and he saw that he was lying on a small grassy knoll. A fire was burning a little distance to his left, and besides the warriors who stood up others were lying down, or sitting in Turkish fashion, gnawing the meat off buffalo bones that they roasted at the fire. The whole scene was wild and barbaric to the last degree and Will shuddered at the fate which he was sure awaited him.

Beyond the Indians he saw trees, but they were not cottonwoods. Instead he noted oak and pine and aspen and he knew he was not lying where he had fallen, or in any region very near it. Straining his eyes he saw a dim line of foothills and forest. He must have been brought there on a pony and dreadful thoughts about his comrades assailed him. Since the Sioux had come away with him as a prisoner they might have fallen in a general massacre. In truth, that was the most likely theory, by far, and he shuddered violently again and again.

Those three had been true and loyal friends of his, the finest of comrades, hearts of steel, and yet as gentle and kindly as women. Hardships and dangers in common had bound the four together, and the difference in years did not matter. It seemed that he had known them and been associated with them always. He could hear now the joyous whistling of the Little Giant, the terse, intelligent talk of Boyd, and the firm Biblical allusions of the beaver hunter. They could not be dead! It could not be so! And yet in his heart he believed that it was so.

He turned painfully on his side, groaned, shut his eyes, and opened them again to see a tall warrior standing over him, gazing down at him with a cynical look. He was instantly ashamed that he had groaned and said in apology:

“It was pain of the spirit and not of the body that caused me to make lament.”

“It must be so,” replied the warrior in English, “because you have come back to the world much quicker than we believed possible. The vital forces in you are strong.”

He spoke like an educated Indian, but his face, his manner and his whole appearance were those of the typical wild man.

“I see that I’m at least alive,” said Will with a faint touch of humor, “though I can scarcely describe my condition as cheerful. Who are you?”

“I am Heraka, a Sioux chief. Heraka in your language means the Elk, and I am proud of the name.”

Will looked again at him, and much more closely now, because, despite his condition, he was impressed by the manner and appearance. Heraka was a man of middle years, of uncommon height and of a broad, full countenance, the width between the eyes being great. It was a countenance at once dignified, serene and penetrating. He wore brilliantly embroidered moccasins, leggings and waist band, and a long green blanket, harmonizing with the foliage at that period of the year, hung from his shoulders. He carried a rifle and there were other weapons in his belt.

Will felt with increasing force that he was in the presence of a great Sioux chief. The Sioux, who were to the West what the Iroquois were to the East, sometimes produced men of high intellectual rank, their development being hampered by time and place. The famous chief, Gall, who planned Custer’s defeat, and who led the forces upon the field, had the head of a Jupiter, and Will felt now as he stared up at Heraka that he had never beheld a more imposing figure. The gaze of the man that met his own was stern and denunciatory. The lad felt that he was about to be charged with a great crime, and that the charge would be true.

“Why have you come here?” asked the stern warrior.

In spite of himself, in spite of his terrible situation, the youth’s sense of humor sparkled up a moment.

“I don’t know why I came here,” he replied, “nor do I know how, nor do I know where I am.”

The chief’s gaze flickered a moment, but he replied with little modification of his sternness:

“You were brought here on the back of a pony. You are miles from where you were taken, and you are the prisoner of these warriors of the Dakota whom I lead.”

Will knew well enough that the Sioux called themselves in their own language the Dakota, and that the chief would take a pride in so naming them to him.

“The Dakotas are a great nation,” he said.

Heraka nodded, not as if it were a compliment, but as a mere statement of fact. Will considered. Would it be wise to ask about his friends? Might he not in doing so give some hint that could be used against them? The fierce gaze of the chief seemed actually to penetrate his physical body and read his mind.

“You are thinking of those who were with you,” he said.

“My thoughts had turned to them.”

“Call them back. It is a waste.”

“Why do you say that, Heraka?”

“Because they are all dead. Their scalps are drying at the belts of the warriors. You alone live as we had to strike you down in silence before we slew the others.”

Will shuddered over and over again. He was sick at both heart and brain. Could it be true? Could those men be dead? The wise Boyd, the cheerful Little Giant, and the grave and kindly Brady? Once more he looked Heraka straight in the eye, but the gaze of the chief did not waver.

“I have hope, though but a little hope,” he said, “that it pleases the chief to test me. He would see whether I can bear such news.”

“If the belief helps you then Heraka will not try again to make you see the truth. What is your name?”

“Clarke, William Clarke.”

“Why have you come to the land of the Dakotas?”

“Not to take it. Not to kill the buffalo. Not to drive away any of your people.”

“But you are captured upon it. The great chief, Mahpeyalute, warned the American captain and the soldiers that they must not let the white people come any farther.”

“That is true. I was there, and I heard Red Cloud give the warning.”

“And yet you came against the threat of Mahpeyalute.”

“Mine was an errand of a nature almost sacred. I tell you again there was no harm in it to your country and your people.”

“Many times have the white people told to the Dakotas things that were lies.”

“It is true, but the sins of others are not mine.”

Will spoke with all his heart in his words. Despite the terrible disaster that had befallen, even if the chief’s words were true, and all his friends were dead, he wished, nevertheless, to live. He was young, strong, of great vitality, and nothing could crush the love of life in him.

“What do you intend to do with me?” he asked.

Heraka smiled, but the smile contained nothing of gentleness or mercy, rather it was amusement at the anxiety of one who was wholly in his power.

“Your fate shall not be known to you until it comes,” he said.

Will felt a chill running down his spine. It was the primal instinct to torture and slay the enemy and the Sioux lived up to it. It was keen torture already to hear that his fate would surely come, but not to know how or where or when was worse. But it appeared that it was not to come at once, and with that thought he felt the thrill of hope. His was unquenchable youth and the vital spark in him flamed up.

“Would you mind untying my ankles?” he said. “You can save your torture for later on.”

Heraka signed to a warrior, who cut the thongs and Will, sitting up, rubbed them carefully until the blood flowed back in its natural channels. Meanwhile he observed the band and counted sixteen warriors, all but Heraka seeming to be the wildest of wild Indians, most of them entirely naked save for moccasins and the breech cloth. They carried muzzle-loading rifles, bows and arrows hung from the bushes and lances leaned against the trees. Beyond the bushes he caught glimpses of their ponies grazing, and these glimpses were sufficient to show him that they had many extra animals for the packs. When he saw them better, then he would know whether his friends were really dead, because if they were their packs and the animals would be there, too. But the chief, Heraka, broke in upon the thought he seemed able to read Will’s mind.

“This is but part of the force that besieged you,” he said. “There were three bands joined. The others with the spoil have gone west, leaving as our share the prisoner. A living captive is worth more than two scalps.”

Will tried to remember all he had ever heard or read about the necessity of stoicism when in the hands of savage races and by a supreme effort of the will he was able to put a little of it into practice. Pretending to indifference, he asked if he might have something to eat, and received roasted meat of the buffalo. He had a good appetite, despite his weakness and headache, and when he had eaten in abundance and had drunk a gourd of water they gave him he felt better.

“I thank you for binding up my wounded head,” he said to Heraka. “I don’t know your motive in doing so, but I thank you just the same.”

The Dakota chief smiled grimly.

“We do not wish you to die yet,” he said, speaking his English in the precise, measured manner of one to whom it is a foreign language. “Inmutanka, the Panther, bound it up, and he is one of the best healers we have.”

“Then I thank also Inmutanka, or the Panther, whichever he prefers to be called. I can’t see the top of my head, but I know he made a good job of it.”

Inmutanka proved to be an elderly but robust Sioux warrior, and however he may have been when torture was going forward he wore just then a bland smile, although not much else. With wonderfully light and skilful hands he took off Will’s bandage and replaced it with another. Will never knew what it was made of, but it seemed to be lined with leaves steeped in the juices of herbs.

The Indians had some simple remedies of great power, and he felt the effect of the new bandage at once. His headache began to abate rapidly, and with the departure of pain his views of life became much more cheerful.

“I never saw you before, Dr. Inmutanka,” he said, “but I know you’re one of the finest physicians in all the West. Whatever school you graduated from should give you all the degrees it has to give. Again, I thank you.”

The Indian seemed not to understand a word he said, but no one could mistake the sincerity of the lad’s tone. Inmutanka, otherwise the Panther, smiled, and the smile was not cruel, nor yet cynical. He stepped back a little, regarded his handiwork with satisfaction, and then merged himself into the band.

“That’s a good Sioux! I know he is!” said Will warmly to Heraka. “Hereafter Dr. Inmutanka shall be my personal and private physician.”

Heraka’s face was touched by a faint smile. It was the first mild emotion he had shown and Will rejoiced to see it. He found himself wishing to please this wild chief, not in any desire to seek favor, but he felt that, in its way, the approval of Heraka was approval worth having.

“Yon eat, you drink, you feel strong again,” said Heraka.

“Yes, that’s it.”

“Then we go. We are mountain Sioux. We have a village deep in the high mountains that white men can never find. We will take you there, where you will await your fate, never knowing what it is nor when it will come.”

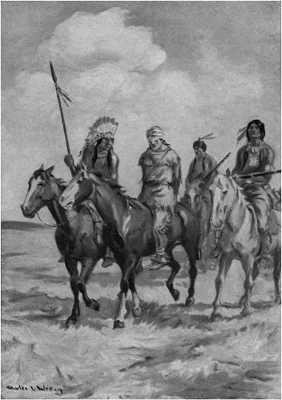

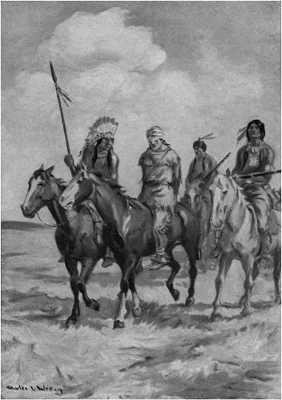

Will was shaken once more by a terrible shudder. This constant harping upon the mysterious but fearful end that was sure to overtake him was having its effect. Heraka had reckoned right when he began the torture of the mind. The chief spoke sharply to the warriors and putting out the fire they gathered up their weapons and the horses. Will was mounted on one of the ponies and his ankles were tied together beneath the animal’s body, but loosely only, enough to prevent a sudden flight though not enough to cause pain. There was no saddle, but as he was used to riding bare-backed he could endure it indefinitely.

Then the chief did a surprising thing, binding a piece of soft deerskin over Will’s eyes so tightly that not a ray of light entered.

“Why do you do that, Heraka?” asked the lad.

“That you may not see which way you go, nor what is by the path as you ride. Soon, with your eyes covered you will lose the sense of direction and you will not be able to tell whether you go north or south or east or west.”

He spoke sharply to the warriors and the group set off. The direction at first was toward the north, as Will well knew, but the band presently made many curves and changes of course, and, as Heraka had truly said, he ceased to have any idea of the course they were taking. He saw nothing, but he heard all around him the footfalls of the ponies, and, now and then, the word of one warrior to another. He might have raised his hands to tear loose the bandage over his eyes, but he knew that the Sioux would interfere at once, and he would only bring upon himself some greater pain.

Will felt that a warrior was riding on either side of him and presently he was aware also that the one on the right had moved up more swiftly, giving way to somebody else. A sort of mental telepathy told him that the first warrior had been replaced by a stronger and more dominant one. Instinct said that it was Heraka, and he was not mistaken. The chief rode on in silence for at least ten minutes and then he asked:

“Which way do you ride, Wayaka (captive)? Is it north, or south, or is it east or west?”

“I don’t know,” confessed Will. “I tried to keep the sense of direction, but we twisted and turned so much I’ve lost it.”

“I knew that it would be so. Wayaka will ride many hundreds of miles, he knows not whither. And whether he is to die soon or late he will see his own people again never more. If he ever looks upon a white face again it will be the face of one who is a friend of the Sioux and not of his own race, or the face of a captive like himself.”

Will shuddered. The threat coming from a man like Heraka, who spoke in a tone at once charged with malice and power, was full of evil portent. Had an ordinary Indian threatened him thus he might not have been affected so deeply, but with the decree of Heraka he seemed to vanish completely from the face of the earth, or, at least, from his world and all those that knew him. His will, however, was still strong. He felt instinctively that Heraka was looking at him, and he would show no sign of flinching or of weakness. He straightened himself up on the pony, threw back his shoulders and replied defiantly:

“I have a star that protects me, Heraka. Nearly every man has a star, but mine is a most powerful one, and it will save me. Even now, though I cannot see and I do not know whether it is daylight or twilight, I know that my star, invisible though it may be in the heavens, is watching over me.”

He spoke purposely in the lofty and somewhat allegorical style, used sometimes by the higher class of Indians, and he could not see its effect. But Heraka, strong though his mind was, felt a touch of superstitious awe, and looking up at the heavens, all blue though they were, almost believed that he saw in them a star looking down at Wayaka, the prisoner.

“Wayaka may have a star,” he said, “but it will be of no avail, because the stars of the Sioux, being so much the stronger, will overcome it.”

“We shall see,” replied the lad. Yet, despite all his brave bearing, his heart was faint within him. Heraka did not speak to him again, and by the same sort of mental telepathy he felt, after a while, that the chief had dropped away from his side, and had been replaced by the original warrior.

Although eyes were denied to him, for the present, all his other faculties became heightened as a consequence, and he began to use them. He was sure that they were still traveling on the plains, so much dust rose, and now and then he coughed to clear it from his throat. But they were not advancing into the deeps of the great plains, because twice they crossed shallow streams, and on each occasion all the ponies were allowed to stop and drink.

Will knew that his own pony at the second stream drank eagerly, in fact, gulped down the water. Such zest in drinking showed that the creek was not alkaline, and hence he inferred that they could not be very far from hills, and perhaps from forest. He surmised that they were going either west or north. A growing coolness, by and by, indicated to him that twilight was coming. Upon the vast western plateau the nights were nearly always cold, whatever the day may have been.

Yet they went on another hour, and then he heard the voice of Heraka, raised in a tone of command, followed by a halt. An Indian unbound his feet and said something to him in Sioux, which he did not understand, but he knew what the action signified, and he swung off the pony. He was so stiff from the long ride that he fell to the ground, but he sprang up instantly when he heard a sneering laugh from one of the Indians.

“Bear in mind, Heraka,” he said, “that I cannot see and so it was not so easy for me to balance myself. Even you, O chief, might have fallen.” “It is true,” said Heraka. “Inmutanka, take the bandage from his eyes.”

They were welcome words to Will, who had endured all the tortures of blindness without being blind. He felt the hands of the elderly Indian plucking at the bandage, and then it was drawn aside.

“Thank you, Dr. Inmutanka,” he said, but for a few moments a dark veil was before his eyes. Then it drifted aside, and he saw that it was night, a night in which the figures around him appeared dimly. Heraka stood a few feet away, gazing at him maliciously, but during that long and terrible ride, the prisoner had taken several resolutions, and first of them was to appear always bold and hardy among the Indians. He stretched his arms and legs to restore the circulation, and also took a few steps back and forth.

He saw that they were in a small open space, surrounded by low bushes and he surmised that there was a pool just beyond the bushes as he heard the ponies drinking and gurgling their satisfaction.

“The ride has been long and hard,” he said to Heraka, “and I am now ready to eat and drink. Bid some warrior bring me food and water.”

Then he sat down and rejoiced in the use of his eyes. Had they been faced by a dazzling light when the bandage was taken off he might not have been able to see for a little while, but the darkness was tender and soothing. Gradually he was able to see all the warriors at work making a camp, and Heraka, as if the captive’s command had appealed to his sense of humor, had one man bring him an abundance of water in a gourd, and then, when a fire was lighted and deer and buffalo meat were broiled, he ate with the rest as much as he liked.

After supper Inmutanka replaced with a fresh one the bandage upon his head, from which the pain had now departed. Will was really grateful.

“I want to tell you, Dr. Inmutanka,” he said, “that there are worse physicians than you, where I come from.”

The old Sioux understood his tone and smiled. Then all the Indians, most of them reclining on the earth, relapsed into silence. Will felt a curious kind of peace. A prisoner with an unknown and perhaps a terrible fate close at hand, the present alone, nevertheless, concerned him. After so much hardship his body was comfortable. They had not rebound him, and they had even allowed him to walk once to the bushes, from which he could see beyond the clear pool at which the Indians had filled their gourds and from which the ponies drank.

One of these ponies, Heraka’s own, was standing near, and Will with a pang saw bound to it his own fine repeating rifle, belt of cartridges and the leather case containing his field glasses. Heraka’s look followed his and in the light of the fire the smile of the chief was so malicious that the great pulse in Will’s throat beat hard with anger.

“They were yours once,” said Heraka, “the great rifle that fires many times without reloading, the cartridges to fit, and the strong glasses that bring the far near. Now they are mine.” “They are yours for the present. I admit that,” said the lad, “but I shall get them back again. Meanwhile, if you’re willing, I’ll go to sleep.” He thought it best to assume a perfect coolness, even if he did not feel it, and Heraka said that he might sleep, although they bound his arms and ankles again, loosely, however, so that he suffered no pain and but little inconvenience. He fell asleep almost at once, and did not awake until old Inmutanka aroused him at dawn.

After breakfast he was put on the pony again, blindfolded, and they rode all day long in a direction of which he was ignorant, but, as he believed, over low hills, and, as he knew, among bushes, because they often reached out and pulled at his legs. Nevertheless his sense of an infinite distance being created between him and his own world increased. All this traveling through the dark was like widening a gulf. It had not distance only, but depth, and the weight it pressed upon him was cumulative, making him feel that he had been riding in invisible regions for weeks, instead of two days.

Being deprived of his eyes for the time being, the other four primal senses again became more acute. He heard a wind blowing but it was not the free wind of the plains that meets no obstacle. Instead, it brought back to him a song that was made by the moving air playing softly upon leaf and bough. Hence, he inferred that they were still ascending, and had come into better watered regions where the bushes had grown to the height of trees now in full leaf.

Once they crossed a rather deep creek, and deliberately letting his foot drop down into it, he found the water quite cold, which was proof to him that they were going back toward the ridges, and that this current was chill, because it flowed from great heights, perhaps from a glacier. They made no stop at noon, merely eating a little pemmican, Will’s share being handed to him by Inmutanka. He ate it as he rode along still blindfolded.

The ponies, wiry and strong though they were, soon began to go much more slowly, and the captive was sure that the ascent was growing steeper. He was confirmed in this by the fact that the wind, although it was mid-afternoon, the hottest part of the day, had quite a touch of coolness. They must have been ascending steadily ever since they began the march.

He soon noticed another fact. The ears that had grown uncommonly acute discerned fewer hoofbeats about him. He was firm in the belief that the band had divided and to determine whether the chief was still with them, he said:

“Heraka, we’re climbing the mountains. I know it by the wind among the leaves and the cool air.”

“Wayaka is learning to see even though his eyes are shut,” said the voice of the chief on his right.

“And a part of your force has left us. I count the hoofbeats, and they’re not as many as they were before.”

“You are right, the mind of Wayaka grows. Some day if you live you will know enough to be a warrior.”

Will pondered these words and their bearing on his fate, and, being able to make nothing of them, he abandoned the subjective for the objective, seeking again with the four unsuppressed senses to observe the country through which they were passing.

The next night was much like the one that had gone before. They did not stop until after twilight, and the darkness was heavier than usual. The camp was made in a forest, and the wind, now quite chill, rustled among the trees. Although the bandage was removed, Will could not see far in the darkness, but he was confident that high mountains were straight ahead.

A small brook furnished water for men and ponies, and the Indians built a big fire. They were now but eight in number. Inmutanka removed the last bandage from Will’s head, which could now take care of itself, and as the Sioux permitted him to share on equal terms with themselves, he ate with a great appetite. Heraka regarded him intently.

“Do you know where you are, Wayaka?” he asked.

“No,” replied Will, carelessly, “I don’t. Neither am I disturbed about it. You say that I shall never see my own people, but that is more than you or I or anyone else can possibly know.”

A flicker of admiration appeared in the eyes of Heraka, but his voice was even and cold as he said:

“It is well that you have a light heart, because to-morrow will be as to-day to you, and the next day will be the same, and the next and many more.”

The Sioux chief spoke the truth. They rode on for days, Will blindfolded in the day, his eyes free at night. He thought of himself as the Man in the Deerskin Mask, but much of the apprehension that must overtake the boldest at such a moment began to disappear, being replaced by an intense curiosity, all the greater because everything was shut from his eyes save in the dusk.

But he knew they were in high mountains, because the cold was great, and now and then he felt flurries of snow on his face, and at night he saw the loom of lofty peaks. But they did not treat him unkindly. Old Inmutanka threw a heavy fur robe over his shoulders, and when they camped they always built big fires, before which he slept, wrapped in blankets like the others.

Heraka said but little. Will heard him now and then giving a brief order to the warriors, but he scarcely ever spoke to the lad directly. Once in their mountain camp when the night was clear Will saw a vast panorama of ridges and peaks white with snow, and he realized with a sudden and overwhelming sinking of the heart that he was in very truth and fact lost to his world, and as the Sioux chief had threatened, he might never again look upon a white face save his own. It was a terrifying thought. Sometimes when he awoke in the night the cold chill that he felt was not from the air. His arms were always bound when he lay down between the blankets and, once or twice, he tried to pull them free, but he knew while he was making it that the effort was vain and, even were it successful and the thongs were loosened, he could not escape.

At the end of about a week they descended rapidly. The air grew warmer, the snow flurries no longer struck him in the face and the odors of forest, heavy and green, came to his nostrils. One morning they did not put the bandage upon his face and he looked forth upon a wild world of hills and woods and knew it not, nor did he know what barrier of time and space shut him from his own people.